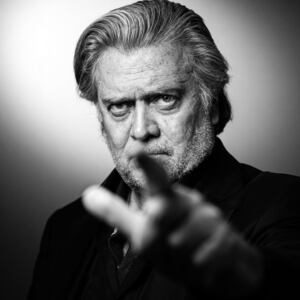

Steve Bannon is trying to lose the battle but win the war.

Faced with a criminal prosecution for the rare charge of contempt of Congress, Bannon is trying to drag members of Congress and key staffers behind the Jan. 6 Committee into testifying at his criminal trial next month, while also requesting sensitive documents he knows he’s unlikely to get.

But that might be the point.

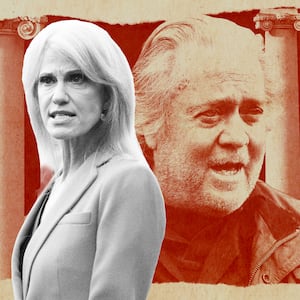

Last week, Bannon’s lawyers issued subpoenas demanding that House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA), two Democratic congressmen, all nine members of the Jan. 6 panel, three committee staffers, and even the House of Representatives’ own lawyer show up and testify under oath. The team is also asking for all kinds of documents—including internal committee communications—to be turned over a few days before trial, which is set to start July 18.

Three former House lawyers said Bannon is asking for things he knows he won’t get, so that when the inevitable happens, it’ll seem as if Congress and the Justice Department are holding back evidence and denying him a fair shot.

Bannon’s own attorney, David Schoen, acknowledged that his team will still come out victorious if the Justice Department tries to block the subpoenas.

“I like the specter of that. We’ve asked for documents that really matter for the American people. I like that optic,” he told The Daily Beast.

If they don’t get the records, Schoen said his team is prepared to ask the judge to simply push back the trial or issue sanctions against the DOJ. Schoen readily admitted that the House of Representatives and the Jan. 6 Committee would be right to try to hold them back under the U.S. Constitution’s “speech and debate clause,” which protects Congress’ internal deliberations from public examination.

Several lawyers told The Daily Beast that Bannon is pulling from the same playbook once used successfully by famed baseball player Roger Clemens when he faced criminal charges of lying to Congress about using steroids, as well as former BP executive David Rainey when he was charged with obstructing a congressional investigation.

When the pitcher and the oil executive were confronted with their separate criminal trials, each made a gamble by demanding evidence they knew they wouldn’t get—and came out on top when politicians refused to play ball.

In both cases, they asked for legally “privileged” congressional records that wouldn’t be released. In Rainey’s case in 2015, when no politician or staffer would waive their right to those privileges, the federal judge thought it appropriate to exclude any evidence of “obstruction of Congress” and dropped that charge. With half the criminal case gone, a New Orleans jury acquitted him of the only remaining charge a few days later.

In Bannon’s case, the Trump-loyal right-wing troublemaker would revel in the opportunity to subject the Jan. 6 Committee’s members to questions under oath in a courtroom filled with reporters—turning the tables on the very same politicians who just weeks earlier were engaged in historic, televised hearings that focused on the way Trump and his followers put the nation’s republic in peril.

But he could also use Congress’ refusal to play ball with his subpoenas as a justification to delay the case. At the very least, Bannon is likely to use any refusal to turn over documents or have members sit for depositions as rhetorical proof that the prosecution is illegitimate.

Schoen enjoys turning the tables. He said having the committee go after Bannon for refusing to respond to a subpoena–only to have the committee ignore a subpoena from Bannon—“sends a terrible message, defaults on their obligations to their constituents and to our national interests and is the height of hypocrisy.”

Such an argument may help him now with the courts, or later with a Republican president sympathetic to Bannon—like Donald Trump.

The former president already pardoned Bannon in the closing hours of his administration, after Bannon was charged with duping thousands of Trump supporters who gave to a fund to build a wall between the United States and Mexico.

It’s easy to envision Trump—or a Trump-loyal president—pardoning Bannon for not helping Democrats with their Jan. 6 investigation.

Stanley M. Brand, an attorney who served as general counsel of the House of Representatives from 1976 until 1983, said Bannon has every right to ask these people to testify.

“First of all, it’s not odd. The House is the complaining witness. They’re the ones who referred this to the Justice Department,” he told The Daily Beast. “I don’t know on what basis the government could say these people don’t have to testify—at least as to the elements of the offense.”

After all, it was the committee’s subpoena to testify and turn over records that was ignored by Bannon in October last year. Members of the Jan. 6 Committee are best positioned to testify in court as to why their demands should have been respected. However, Brand said the federal judge overseeing Bannon’s case would be wise to limit the kinds of questions they could ask Chairman Bennie Thompson (D-MS) or Co-Chair Liz Cheney (R-WY).

“They’re not going to have a free-roving commission to get at everything extraneous to the prosecution of this case. This is a criminal contempt case where the government has the burden to prove beyond a reasonable doubt, but that's not going to allow Bannon’s team to wholesale forage through the committee or the Justice Department. There will likely be some legal combat over that,” he said.

Bannon’s requests dig deep. The subpoenas ask for never-before-seen records that would show the committee’s staffing and budget, internal communications of an ongoing investigation, and anything that touches on people’s dislike of the guy.

Take this item in the subpoena: “All documents in your possession that reference making an example of Mr. Bannon, punishing him, hoping to influence or affect the conduct of other potential witnesses before the Select Committee, or words or similar meaning and effect.”

But putting the House’s top lawyer on the stand would also allow Bannon to challenge the legitimacy of the panel itself. Bannon’s defense attorneys want to seize on the fact that Doug Letter, the House’s general counsel, told FBI agents last year that Cheney wasn’t technically a ranking member—a fact that they hope to use to show that the committee doesn’t have the authority to issue subpoenas like the one Bannon ignored.

Bannon using these subpoenas “as a tool to rummage… I don’t think that’s going to work,” Brand added.

Then again, U.S. District Judge Carl Nichols has already shown concerns over the way the Justice Department has handled its case against Bannon following The Daily Beast’s reports that revealed the FBI spied on another of his defense lawyers, Bob Costello—and cast a wide dragnet that surveilled other Costellos who clearly weren’t him.

Brand has had his own interactions with the Justice Department over the same types of accusations. He represents Trump’s former White House deputy chief of staff, Dan Scavino, who also ignored the Jan. 6 Committee’s subpoena demanding that he testify but ultimately wasn’t prosecuted by the Justice Department.

Charles Tiefer, another attorney who served as acting general counsel for the House from 1993 until 1994, said Bannon’s aggressive tactics haven’t been employed widely since the Red Scare in the 1950s. He pointed out that Hollywood figures and labor union leaders accused of being communists often resorted to subpoenaing members of Congress as an aggressive defense, putting the pressure back on politicians.

But Tiefer doesn’t expect it to work for Bannon, who has a history of gleefully seeking the destruction of democratic institutions.

“He has to get the court’s approval to subpoena members and staff of House investigations. Judges do not like being manipulated into doing the crazy things that Bannon wants,” he told The Daily Beast.

And that applies particularly to a case as simple and as sensitive as this one. While the accusation against Bannon seems simple to prove—he didn’t show up or hand over documents—the case still involves fundamental constitutional questions. After all, a member of the judiciary will decide if a one-time adviser to the former president should have ignored his claim of executive privilege to testify before a legislative panel.

“I doubt that the courts will want to get themselves involved in becoming mobile inquisitions against all three branches,” Tiefer said.