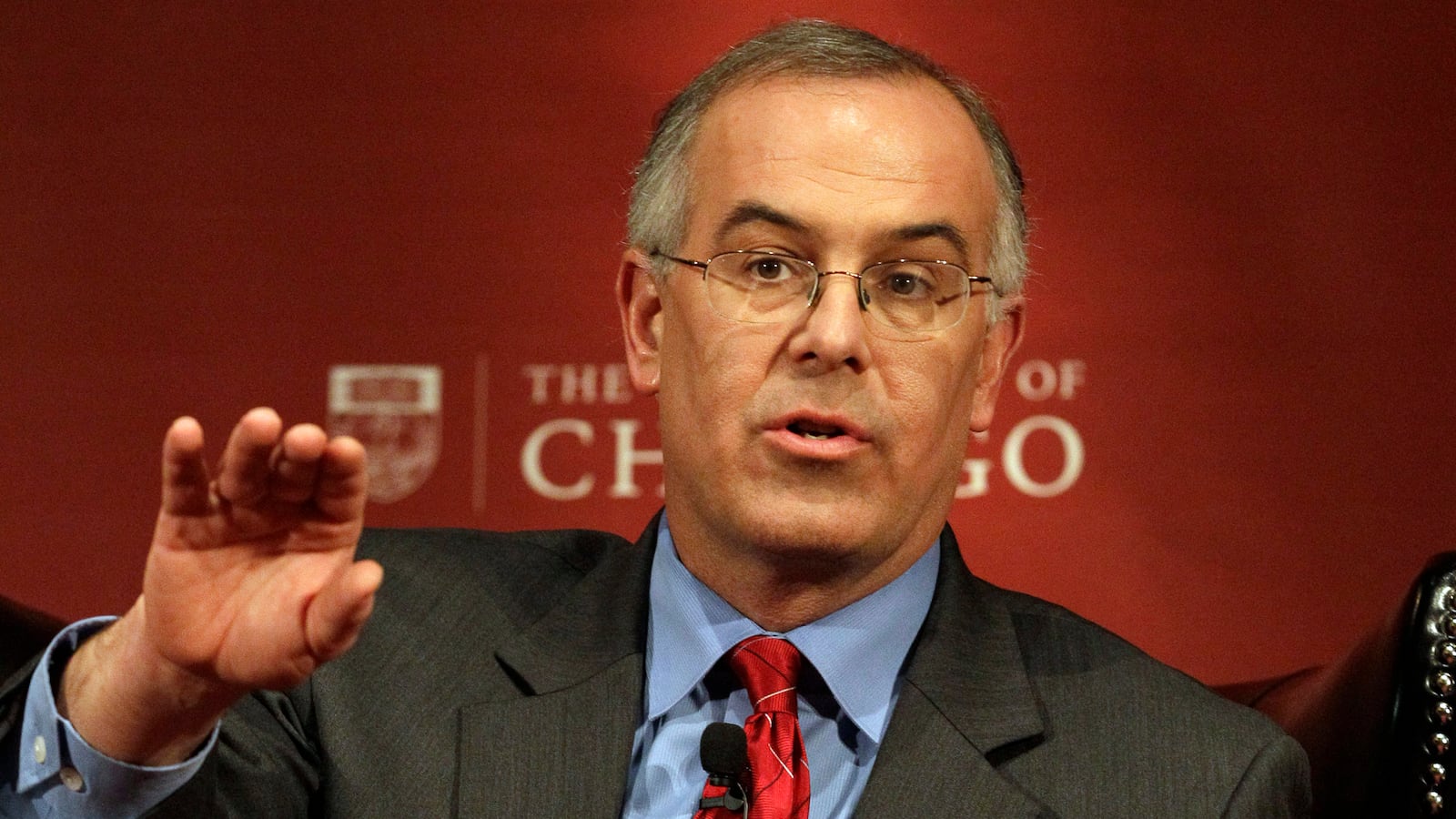

We learned something interesting from a New York Times column by David Brooks, discussing a new book by Ta-Nehisi Coates. Coates argued, and Brooks agreed, that the different perspectives of blacks and whites regarding the so-called American Dream arise from history. Here’s Brooks, writing to Coates:

My ancestors chose to come here. For them, America was the antidote to the crushing restrictiveness of European life, to the pogroms. For them, the American dream was an uplifting spiritual creed that offered dignity, the chance to rise.

Your ancestors came in chains. In your book the dream of the comfortable suburban life is a “fairy tale.” For you, slavery is the original American sin, from which there is no redemption.

Fair enough, and this point has been discussed many times before.

What interested us was how this applies to Brooks himself: not his experience as a white person (we could care less) but his experience as a journalist.

As regular readers of our blog know, Brooks is embattled as a journalist. He makes error after error but refuses to correct or even admit his mistakes. And this has puzzled us.

Just coincidentally, in an earlier attempt to understand Brooks’s stubbornness and seeming indifference to facts, we’d turned to the writing of ... Ta-Nehisi Coates, who’d discussed the code of the streets, which is characterized by a don’t-back-down ethos, and it had struck us that journalists such as Brooks live by the same code. To admit error would be to show weakness.

To us, it seems only human to make mistakes and only responsible to admit them. But Brooks, living on the street as it were, feels like he has to stay strong.

From our perspective, Brooks’s refusal to admit error makes him look like a buffoon. But maybe we’re just judging him based on the norms of another culture. For us to disparage Brooks for spreading untruths is analogous to Brooks disparaging some ghetto-dweller for committing petty crime. Coates had written, "Respect and reputation are everything there. These values are often denigrated by people who have never been punched in the face.”

Here’s the funny thing, though. We're journalists, too—we write for The Washington Post and The Daily Beast, we’ve even written for The New York Times on occasion—and we don’t feel the need to live by these “street” values. So what gives?

From the world of the streets to the world of journalism

We can understand this by looping back to Brooks’s recent column. He wrote how his ancestors came to this country voluntarily rather than being kidnapped by slave traders, and so he can feel comfortable with the American Dream.

Our experience as journalists is similar to Brooks’s as an American: We came to journalism voluntarily, and we believe in the “journalistic dream” in which our job of truth and transparency, comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable. Brooks’s experience as a journalist is different. He wasn’t kidnapped into the profession, but he doesn’t have the freedom that we’ve had. He’s had to shimmy up the greasy pole of success and he’s always worried about slipping back down.

We’re the “white person” in this scenario: Our status is assured, we’re comfortable with our place in journalistic society, and we don’t have to do anything special to keep people’s trust. We can have ideals and believe in the system, and from our comfortable perch we can feel free to criticize people who don’t live up to recognized standards of behavior.

Brooks is the “black person” here: No matter how well he’s doing, he’s continually reminded that his status is contingent. Every day he has to prove himself, he has to justify his existence, he always has to worry that people like us will seem him “walking down the street,” as it were, and thinking he doesn’t belong. If he has to break the rules to stay where he is, he’ll do so. After all, the rules weren’t written by people like him.

Check out this quote from Brooks:

Am I displaying my privilege if I disagree? Is my job just to respect your experience and accept your conclusions? Does a white person have standing to respond?

If I do have standing, I find the causation between the legacy of lynching and some guy’s decision to commit a crime inadequate to the complexity of most individual choices.

He’s writing to Coates, but this could be us writing to Brooks. We find the causation between the legacy of journalism and some guy’s decision to commit an ethical violation (not correcting known errors) inadequate to the complexity of most individual choices.

From our perspective, Brooks spreading anti-Semitic false statistics in the pages of The New York Times is actually much worse than Eric Garner selling loose cigarettes on the streets of Staten Island.

But that’s just our perspective. Maybe our judgmental attitude toward sloppy journalism is as clueless as Brooks’s attitude toward street crime. We don’t know. We’d be interested to hear what Coates has to say. We think all of this relates to the problem we’ve noticed many times in science, that researchers and journalists will go to great lengths to avoid admitting that they may have made mistakes.