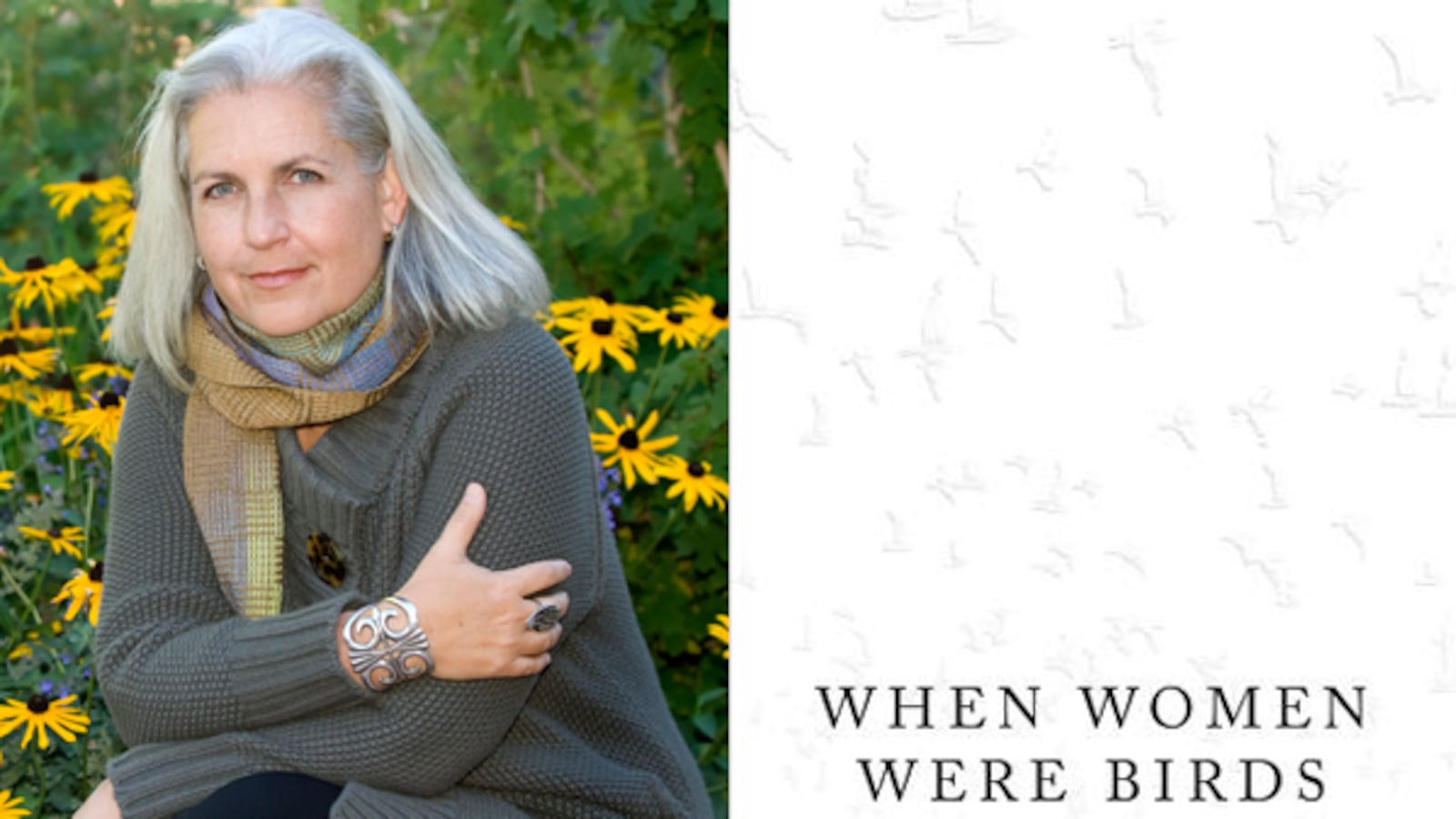

Mountain time: Terry Tempest Williams is at home in Utah, and I’m in Los Angeles, flabbergasted by her warmth, even over the phone, by her graciousness, intuition, and intimacy. She is comfortable with distance and interruption; with poor phone connections and tesserated thoughts. Everything Williams has ever written, from her first book, The Secret Language of Snows, written for children in 1984, to her latest, When Women Were Birds: Fifty-Four Variations on Voice, finds its roots in the precariousness and uncertainty of life and grows from there, skyward.

Williams has loyal readers. Her lectures and readings—held in far corners and small towns as well as distinguished, big-city venues—are always packed. Why? Because she’s the kind of writer who makes a reader feel that his voice might also, one day, be heard. Why? Because she cancels out isolation: connections are woven as you sit in your chair reading—between you and the place you live, between you and other readers, you and the writer. Without knowing how it happened, your sense of home is deepened reading her work, dug out, the soil pressed down around you as if you were a plant the author promised to water. It’s the strangest thing.

Williams was born into a large Mormon clan in northern Utah. Mormon women are expected, she explains, to keep journals and bear children. The author is fond of saying that the only things she has done religiously in her life are keep a journal and use birth control. When Williams’s mother died at 54, she left Terry, then 22, shelves and shelves of brightly bound journals.

Williams opened them. They were blank.

It has taken her 35 years to begin to understand and write about what this meant to her. “Honestly, I buried this story,” she says, the wind whistling through the phone; helicopters overhead in L.A. “I did not save or cherish those journals. I wrote in them unceremoniously. It wasn’t until I turned 54, the age she was when she died, that I realized how terrified I had been of my own blank mind.”

Williams comes from a long line of storytellers—her writing tends to unfold, layer by layer. “When I write, I put one foot in front of the other. It’s an act of faith. I just follow my heart.” She talks in a prismatic way that I find perfect for the telephone—a back and forth of recognitions, observations, and phrases. Narrative is difficult by phone—plot cannot be interrupted, conversations are so often one-sided. But with Williams, talking fits the crackle and whistle, the distance of long-distance telephone talk. She never fails to listen for a response, to ask what the person on the other end of the line is thinking.

Williams searched for her mother’s voice in this book about voice. She realized how much mothers traditionally withhold their voices to let their children develop their own. My mother, she writes, was “largely quiet and graceful. A letter. A meal. A walk together. Her touch.”

Wandering back over her 54 years, the writer stumbles on stories she’s never told—buried stories, terrifying memories. Here’s where the faith comes in: telling the truth about her life. Writing things out loud. “The only book worth writing,” she tells me (and I imagine the vast, wild silence around her house) “is the book that threatens to kill you.”

“I grew up in a culture in which it was a sin for a woman to speak out.” And yet, she has spent her life speaking out. Her fourth book, Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place, published in 1991 when Williams was 36, told the story of how 10 women in her family, living downwind from the atomic-testing grounds in Utah, had died from or been diagnosed with breast cancer. But it was also about the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge, threatened by the flooding of the Great Salt Lake. She protested nuclear testing in the Nevada desert in the 80s and early 90s, testified before Congress on women’s health and environmental links to cancer, and against the war in Iraq. She has fought for the preservation of wilderness, threatened species, and human dignity at home and around the world. Her book, Finding Beauty in a Broken World, tells of time spent with prairie dogs and time spent in Rwanda, listening to stories of the genocide, traveling in its wake. It is also the story of how she came to adopt her grown son, Louis, who is from Rwanda, and how his presence changed her life forever.

Williams has written candidly about the loneliness of marriage. But she also says that her husband, Brooke, whom she married in 1977, and who also grew up in the Mormon community, is her “safe place. Brooke is the caretaker of my voice,” she says. “We recognize each other as refugees from the dominant culture.”

Toward the end of When Women Were Birds, Williams writes about the discovery of a cavernoma (a benign vascular tumor) that caused and periodically continues to cause, bleeding in her brain. “This is not my story,” she told herself again and again. “This is not my story.” When the brain bleeds, she says, “I can speak, but my right side goes numb. I lose strength. It’s a very different way of being in the world.” “It feels,” she tells me, “like being underwater; like the landscape around me is eroding. I feel like a sea anemone in a tide pool.” “How well do you live with uncertainty?” the doctor asked Williams when she was asked to decide whether or not to undergo neurosurgery. “What else is there?” she said.

She began to dream, in earnest, of birds.

In the end, this is a book about privacy and blank pages. “I will never be able to say what is in my heart,” she writes, “because words fail us, because it is in our nature to protect, because there are times when what is public and what is private must be discerned.” While so many of Williams’s earlier books were about speaking up and out, this book about voice, it turns out, is about discernment and silence; about all the things that cannot be said. “Once upon a time,” she writes, “when women were birds, there was the simple understanding that to sing at dawn and to sing at dusk was to heal the world through joy.”