At the highest navigable point of the Congo River, thick jungle creates an impenetrable wall of green around a large island. Apart from the dug-out canoes transporting bundles of thin trees from its shores, there’s little sign that the land is inhabited. But just up the steep river bank and through the brush is an opening. Here, a cluster of nearly 20 narrow homes is the jungle-eaten remnants of a once prosperous plantation town that was left to rot when the Belgian colonialists granted the Democratic Republic of the Congo independence half a century ago.

Belgika, as the island is known, doesn’t get many visitors. Many years ago, when the country was the Belgian Congo, it was a hub for foreigners who would come from the nearby city of Stanleyville to vacation amid the abundance of wildlife. In the 54 years since they departed, Belgika has been forgotten by the outside world. The most recent visitor, villagers say, was an African-American man who came to do prospecting for the World Bank a few years ago.

The city of Stanleyville—now called Kisangani—was a majestic port city as deep as one can go into the Heart of Darkness. It was this area that inspired a young steamboat captain-turned-author named Joseph Conrad to place a crazed Kurtz in his Inner Station. During the first half of the 20th century, the city’s whitewashed glamor drew well-heeled European visitors and Hollywood stars like both Audrey and Katherine Hepburn. The African Queen was filmed here.

But after those glory days, Kisangani's reputation took a turn. It was the epicenter of the many wars that have eroded the Democratic Republic of Congo’s stability and the remnants of this decline are widely visible: cranes that once manned the city’s busy port hang in disuse and a railway station runs only one train per week. The speed boats that used to race up and down the Congo River are long gone, and to travel the 20 miles to Belgika you have to commit to a journey of at least six hours round trip in a thin, dug-out wooden canoe. After decades of violence, flights to Kisangani are unpredictable and Western tourists are virtually unheard of.

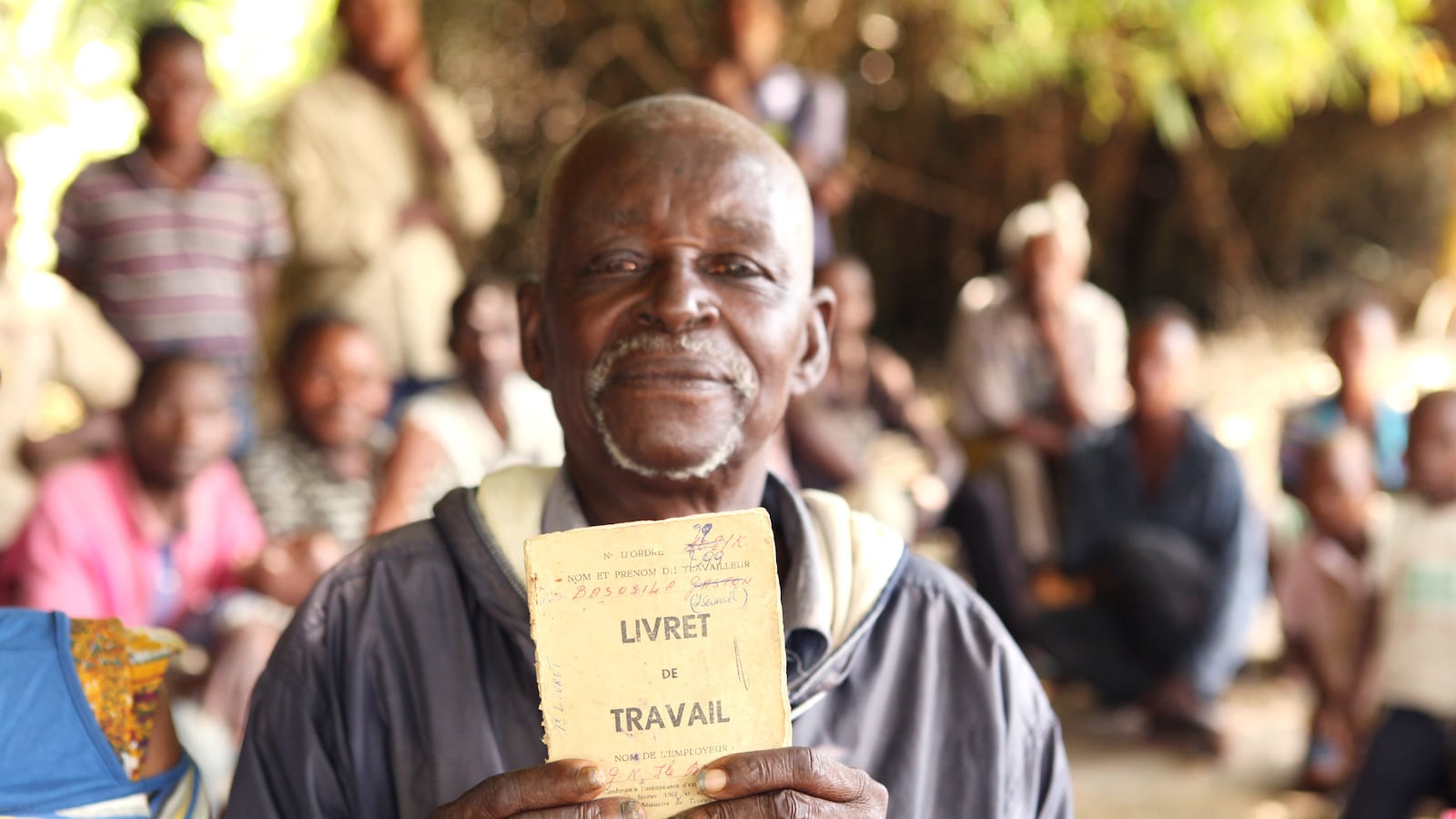

So, the arrival of a foreign journalist in Belgika merits a town meeting. Dozens of villagers gather in a circle under the shade of palm trees, with plastic chairs proffered for guests and three elderly men who position themselves in the middle. In a place with little written history, these men hold the island’s memories.

Basosila Botala is wearing a blue rain jacket despite the sweltering heat. The cheery 69-year-old father of eight sits in the center with his wife and delicately brandishes a small, brown book. “Livret de Travail” is printed on the frayed tan cover: it’s the workbook he used as an employee on the Belgian plantations that covered the island.

Once, they say, the island was known as a prosperous rubber plantation and resorting spot for Belgian colonialists. Now, the jungle has taken over. The foundations of the brick and stucco buildings that were constructed in the 1940s and ‘50s to house the white workers are exposed and crumbling. Thatch or scrap material covers hollow doors and windows. On the outskirts is the shell of an old brick church, still laid with tile flooring, but the pews are just cinder blocks and wooden planks. Walls are covered with roughly drawn Biblical scenes featuring a dark-skinned Jesus. The bell tower bellows loudly when a little muscle power is put into it.

The men say their village is home to 360 people, and that there are two other similar, but smaller, towns on the island, all occupying the old Belgian barracks. These villages used to harvest rubber, cacao, palm oil, and coffee beans. But there’s little industry coming from the island today, despite having the fertile land of one of the world's most resource-rich countries.

The name Belgika comes from a mining company that was founded in 1897, when the country was still personally owned by the Belgian King Leopold. Under his reign of terror, an estimated 10 million Congolese died during his quest for resource extraction.

The company moved into what was called Bertha Island, and soon become synonymous with the land it occupied. A 1907 contract leases the plot of land to the Belgika corporation for five years, but it stayed for much longer.

In the 1950s, the Belgika company reportedly owned 1,500 hectares of rubber trees on the island, along with holdings across the eastern part of the Congo. It was headquartered in Stanleyville, in a tall corner building that still stands in the decrepit, yet lively, downtown. Only the L, K, and A of the old sign remain stuck to the side of the office.

Then, in 1960, Belgium hastily withdrew from its colony. The newly free country struggled to maintain order in the wake of independence, but it was woefully unprepared. At that time, only 16 Congolese were known to have college degrees.

On Belgika, Botala and his family watched as the white men loaded their families into a large boat and took off for Kisangani. From there, most would return to Europe. He recalls that word of independence wasn’t happily received when it first reached the island. “Here it wasn’t good news,” he says. “There was confusion because our fathers were no longer going to work.”

“Life was much better than now,” Botala says of colonialism. Despite their ranking as lower than second-class citizens in their own country, this is a view echoed widely by residents of the region. “At that time we had things we’ve never had since.” He begins to list them off: food rations, health clinics, education. “We were never chased out for (lack of) school fees,” Botala says.

Another man chimes in: “Today we are living at the edge of suffering.”

When asked who’s to blame for the country’s downfall Botala says, "independence."

Stanleyville and Belgika were again thrown into disarray in 1964 when a rebel movement seized a huge swath of the region and declared it sovereign. These insurgents, who called themselves Simba, or “lion” in Swahili, brutally murdered civilians and orchestrated one of the largest hostage crises in history when they held nearly 2,000 Americans and Europeans captive for four months in Stanleyville.

Botala remembers that the rebels would pull into the island, loot what they could, and then take the haul back to Stanleyville. The villagers left their homes and hid in the forests for about a year. At one point he says, Laurent Kabilia—a Simba leader who would become president of the country 30 years later—landed in a helicopter stolen from Joseph Mobutu—then commander of the Congolese Army and soon-to-be dictator—and demanded oil to fuel their ships.

The plantations chugged along for a few years after the rebellion was quashed by a squad of mercenaries and Congolese soldiers, but they never again created the prosperity the island had under the Belgians.

The island’s resources are still there, but investment and infrastructure are sorely lacking. Wielding a curved knife, a young man navigates past the aging structures and into the forest. At the edge of the homes, a group of women dressed in bright sarongs beat sticks together and raise their voices in song as they bury a young boy. Nearby, a tailor in a blue jersey and American flag shoes works a sewing machine, piecing together a traditional colorful Congolese dress. The young man weaves through clusters of bamboo and cuts a diagonal slash into a tree, positioning a hollow log at the end. Slow at first, then steadily, a stream of liquid drips off the incision. It’s rubber: the resource that made the island—and the country—famous.

“If we’re in chaos today it’s because we chased many private business people out,” says Martin Kifukoya Lometcha, an authoritative businessman with a Congolese flag garnishing his suit lapel. “When it doesn’t have international business, it’s a dying country.” He speaks while sipping a soda in the restaurant of the Residence Victoria in downtown Kisangani. It was once the most glamorous hotel in town, but in 1964, hundreds of European hostages were held captive in its rooms. It never functioned as a hotel again and today is inhabited by more than 400 people.

Lometcha works a thousand miles away in the counseling office for the national senate in Kinshasa, Congo’s capital, but he has owned part of Belgika since 1971, when it was taken from whites under Mobutu’s program of Zairianization, which involved evicting all remaining Europeans and seizing their holdings in order to transfer power back to the locals and erase all remaining vestiges of colonialism.

Lometcha refuses to discuss the earlier history of Belgika—more than once he retorts, “Ask the Belgians!”—but he remembers that at one point, Belgika was a conglomeration of three companies: one working in rubber and palm oil production; a construction company; and a supplier of tractors and heavy machinery. He also recalls the many visitors who would often go to the island to admire its harvests and wildlife. “The tourism of science,” he calls it. The forests were lush and filled with life, from giant snakes to monkeys. When a top Mobutu confidant named Colonel Alphonse Bangala purchased the island, Lometcha bought shares. After years of failed attempts to enliven its industry, he’s now trying to sell them off.

Four miles farther along the rim of the island from Botala’s village, a cluster of canoes and sacks of rubber are waiting on the shore—where wild vines snake from trees and dip into the muddy water—destined for the markets of Kisangani. A large mansion that was once home to the last European resident—an Italian businessman who left in 1977—is now occupied by many people. Small rooms off its graffiti-covered foyer provide shelter from the thick rain that can unexpectedly, and vengefully, hit.

In this smaller town, there are only five families, the village chief says. A Belgian church has a chalkboard sitting at the pulpit with the jungle peeking through the windows behind it. A couple more miles along the island is the ruin of the European’s living quarters, villagers say, including what was once a hotel. But the sunlight is threatening to fade and a three-and-a-half-hour river journey back to Kisangani looms.

Along the river, crumbling remnants of an active trading hub are overtaken by nature. A tugboat improbably sits high on the bank, obscured by tall grass, a broken oil rig hangs over the water nearby. A sign peeking out from the heavy forest is barely visible on the trip back. It reads: “Le Service Maritime.” When many international ships plied these waters, these signs were used to direct them, but the small boats now bringing goods to the local market hardly need such guidance.

The International Women’s Media Foundation supported Nina Strochlic’s reporting from the Democratic Republic of the Congo.