PHOENIX—For someone who feels nothing less than the weight of “the republic and the free world” on his shoulders every day, Adrian Fontes is having a pretty good time.

On Thursday night, at an Arizona Democratic Party event geared toward Latinos, Fontes gave a sober but upbeat speech about his campaign for Arizona Secretary of State. “Elections are the golden thread that runs through the entire fabric of our society, and they bind us together,” he said. “That golden thread, if you pull it out, the entire fabric disintegrates.”

When he was done, a four-piece mariachi band seemed to materialize out of nowhere, and in a split second, Fontes had grabbed the mic. The crowd—clutching neon-colored tequila cocktails with names like the “Blue Wave”—cheered and whistled as Fontes belted out the ballad “El Rey.”

For Fontes, that may have been more of a survival mechanism than a schtick. In an interview before his speech, he talked about the enormous responsibility he bears in his campaign against his Republican opponent, Mark Finchem, who is perhaps the most hardline election denier and conspiracy theorist on the ballot for a major office this November.

“I do it with some semblance of joy,” Fontes said, sipping a margarita on ice. “Because if I really didn't approach it with a bit of grace, then it would be very, very heavy.”

Heavy is a delicate way to put it. Many people beyond Fontes believe the fate of American democracy will be shaped by whether he keeps Finchem away from running the election system of one of the nation’s most pivotal battlegrounds.

National donors and Democratic Party organizations have flooded the state with cash for him, and Rep. Liz Cheney (R-WY) has run TV ads urging Arizona voters to stop Finchem. At an event in the state in October, Cheney said “what happens here in Arizona is not just important for Arizona, but it’s important for the nation and for the future functioning of our constitutional republic.”

The final stretch of the 2022 campaign in Arizona has offered a stark reminder of the forces that Finchem and others have helped to unleash. Loosely organized armed vigilantes have begun to appear at ballot drop boxes in Maricopa County to “monitor” those who drop off ballots, which has had the obvious effect of intimidating and scaring voters and poll workers.

The possibility of quelling those forces is what spurred Fontes into this race. A Mexican-American former Marine from the border town of Nogales, he experienced the outbreak of election denialism firsthand. In 2020, he was the top elections official in Maricopa County, home to 2.5 million voters.

More than maybe anyone else, Fontes knew that he could end up as the only person standing between a Big Lie believer and the power of administering Arizona’s elections. But he might not have predicted that his opponent would instead be a high priest of 2020 election denialism.

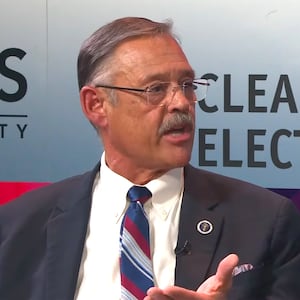

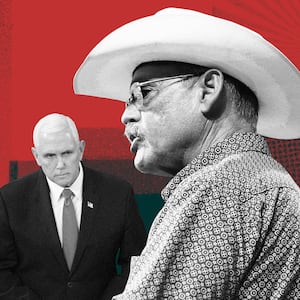

A cowboy-hat wearing Oath Keeper who was present at the Capitol on Jan. 6, Finchem has been a key spreader of many beliefs that have come to define the Big Lie movement, like arguing that Arizona lawmakers should install their own presidential electors. In his campaign, he has courted and rubbed elbows with a rogues’ gallery of QAnon conspiracy theorists and antisemites, and has vowed to end mail-in voting altogether.

Fontes describes his opponent as a “fascist” and “the quintessential election-denying, Oath Keeping, white nationalist guy that exists in the country.” He describes himself as “the guy who oversaw the election scrutinized by the cyber ninjas… I’m the one who ran that bipartisan team that preserved and protected democracy and Arizona”

“You could not find a more diametrically opposed race in the country,” Fontes said. (The Finchem campaign didn’t reply to a request for them to respond to Fontes’ remarks.)

Despite the enormous risks, Fontes said he’d prefer that race to one against a more moderate Republican. It may make people anxious, or even downright uncomfortable, but Fontes seems to believe that a direct clash between himself and Finchem is the only way to begin breaking the fever that has gripped this state and the country.

“I would be lying to you if I said that I didn’t actually secretly hope that it would happen,” he said of Republicans nominating Finchem. “Facing major challenges is something that very few people get to do, and facing a challenge as significant as this, really, it means a great deal.”

“It’s comeuppance for the country,” he said. “It’s definitely an inflection point for democracy in America, and it’s a real political challenge for our citizenry across the board… Are we going to devolve away from the rule of law? Are we going to shove our way backwards?”

With the election days away, those questions seem closer to reality than not. There has been sparse polling of the race, but one survey from Phoenix-based OH Predictive Insights saw Finchem leading Fontes, 40 percent to 35 percent, with a quarter of voters undecided.

Fontes is also coming off a defeat in a race where his election administration policies were a central issue. In November 2020, as Democrats saw victories in Arizona, a Republican defeated him in his bid for another term as Maricopa County Recorder.

During his tenure, Fontes heavily promoted vote-by-mail measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic; in March 2020, a court blocked his plan to send a ballot to every Maricopa County voter.

Many of those anxious about Finchem are paying close attention to dynamics in the governor’s race, which could help lift the Republican to victory. Democrats are also concerned about the campaign of Katie Hobbs, the incumbent Democratic Secretary of State, as Kari Lake—herself a hardline MAGA candidate who denies the 2020 election—opens up a lead in polls.

In his own race, Fontes has pursued a different strategy than Hobbs, who declined to share a debate stage with Lake, arguing that such a forum would give a platform to the Republican’s fringe ideas and create a spectacle.

In September, Fontes appeared alongside Finchem for a debate, where it took the Republican virtually no time to begin delving into conspiracy theories about faulty voting machines and ballot boxes stuffed with fake ballots.

That night, Finchem had a platform—but Fontes had one, too, and he said leveraging it was crucial to “identify a very bright difference between the two of us” to Arizona voters. Onstage, the Democrat executed his plan to the letter, calmly taking apart Finchem’s conspiratorial claims, and putting him on the defensive.

“He was crazier than I expected him to be, earlier than I expected him to be,” Fontes said. “We wanted to get him to tighten up his voice, get shrill, start acting crazy, which is what we know he’s got a penchant for doing… He went like a rocket right off the bat.”

“From that point on, all I had to do was show the contrast between maturity, cool-headed, calm, collected, knowledgeable leadership, versus his erratic, loud, screeching showmanship,” Fontes added.

Asked if Hobbs would have benefited from striking that kind of contrast with Lake, Fontes said he wasn’t going to second-guess his ticketmate, whom he called a “solid leader.” But he indicated that he might have done things differently.

“I don’t know that I would have made the same decision, but I’m not running against Kari Lake, and I’m not Katie Hobbs, so it’s not fair for me to say whether or not she was right or wrong,” he said. “But the fair answer for you is, I do think that was a missed opportunity.”

Many in Arizona, and beyond, were relieved to see Fontes go toe-to-toe with Finchem, and Arizona insiders have been impressed with the campaign he has run.

After facing an initial fundraising disadvantage, Fontes has begun to outraise Finchem, as typically sleepy races for secretary of state take on national significance with election deniers running in key states like Arizona, Michigan, and Nevada. As of late October, Fontes had raised $2.4 million to Finchem’s $1.8 million.

Nationally, Democratic donors and organizations are backing candidates like Fontes with serious money. The Democratic Association of Secretaries of State announced in September that it would bankroll an ad campaign of $10 million to $14 million, split between Arizona and Georgia.

Far from having to knock down doors to convince donors that he needed cash, Fontes told The Daily Beast that much of the support has materialized organically. “National Democrats… understood that for us to lose this spot, for us to lose this race, risks far more than just the Electoral College votes in one state,” Fontes said.

In Arizona, Fontes is hoping to cobble together a diverse coalition of Democrats, independents, and even Republicans who are alarmed by the prospect of Finchem running Arizona elections. In September, Joel John, a GOP state lawmaker, publicly endorsed Fontes, calling it “frankly frightening having someone like that be a heartbeat away” from the governor’s office. (In Arizona, the secretary of state is the first in the gubernatorial line of succession.) The opinion, unsurprisingly, is shared by Democrats who served with Finchem at the state capitol. “The crazy that’s out on the campaign trail right now is only a fraction of the crazy that he actually is,” said Martín Quezada, a Democratic state lawmaker, now running for State Treasurer. “I mean, this guy is as scary as people think he is. He has been that scary as a legislator for the last several years.”

Win or lose, Finchem is poised to get the votes of well over a million Arizonans. Even if Fontes believes that this race offers an opportunity to drive a stake into the heart of the Big Lie movement, it is inevitable there will be a large share of votes for someone he believes is a “fascist.”

Finishing his margarita before his speech, and impromptu mariachi singing, the heaviness of that thought didn’t seem to bother Fontes.

“So what?” he said. “As long as there’s more people to vote for me, we’re in good shape.”