Criticism of President Donald Trump’s go-back-where-you-came-from tweets seems sure to continue in the coming months. That’s as it should be, but what has been missing from criticism of the president’s derogatory tweets is the ridicule they merit.

The president, who has not told his white critics to return to their countries of origin, has been treated with too much dignity in the latest controversy he created. When it comes to Trump’s racism, critics have been reluctant to stoop to his level of invective, lest they sound like him while attacking him. But there still remains plenty of room for ridicule. How, for example, would the president react to being parodied, telling his critics with Scandinavian ancestry to go back to the ice countries from which they come? With a president as thin-skinned as Trump, the power of demeaning laughter cannot be underestimated.

A classic example of how telling ridicule can be in dealing with racism like the president’s may be seen in the opening chapter of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. There the novel’s richest and most arrogant figure, Tom Buchanan, advances a Trump-like defense of white supremacy that is quickly made to look preposterous.

Tom is the inheritor of vast wealth, the owner of a massive estate, and the unfaithful husband of Daisy Buchanan, the woman loved by Jay Gatsby, the titular character of Fitzgerald’s novel. In the midst of a casual visit from Nick Carraway, the narrator of The Great Gatsby, Tom suddenly begins to lecture on his racial theories. “Civilization’s going to pieces,” Tom declares, citing as his authority a book titled The Rise of the Colored Empires.

“The theory is if we don’t look out the white race will be—will be utterly submerged. It’s all scientific stuff; it’s been proved,” Tom insists. Tom’s self-assuredness in combination with his vagueness about “scientific stuff,” prompts Daisy, to remark, “Tom’s getting very profound. He reads deep books with long words in them.”

Daisy’s sarcasm doesn’t slow Tom down. “It is up to us, who are the dominant race, to watch out or these other races will have control of things,” Tom goes on to say, ignoring Daisy, who turns to Nick and with a wink adds, “We’ve got to beat them down.”

Nick is shocked by the fervor of Tom’s defense of those he calls Nordics. Nick’s shock stems from how mindlessly Tom has bought into the racism he is espousing. Fitzgerald has allowed Tom to undo himself with his own zealotry.

And therein lies the brilliance of Fitzgerald’s ridicule. Tom’s ideas were very much part of American life in 1925, the year The Great Gatsby was published. In 1916 Madison Grant published his influential The Passing of the Great Race, which warned that Nordics were in danger of being swamped by people from inferior countries, and in 1920 Lothrop Stoddard’s racist apologia, The Rising Tide of Color, appeared.

Grant’s and Stoddard’s ideas of who made a good American were ones that resonated politically. One year before The Great Gatsby was published, Congress passed the restrictive Johnson-Reed Immigration Act of 1924 which put into place immigration quotas that favored Northern Europeans by limiting immigration to the United States to 2 percent of each nationality according to the 1890 census.

In mocking Tom, Fitzgerald’s point was not that Tom’s ideas weren’t dangerous. His point was that they lacked substance. Today, the president is more likely to be ridiculed on Saturday Night Live than in a novel, but where the ridicule takes place is unimportant. What is essential is that the ridicule be part of public outrage over the president’s go-back-where-you-came-from declarations.

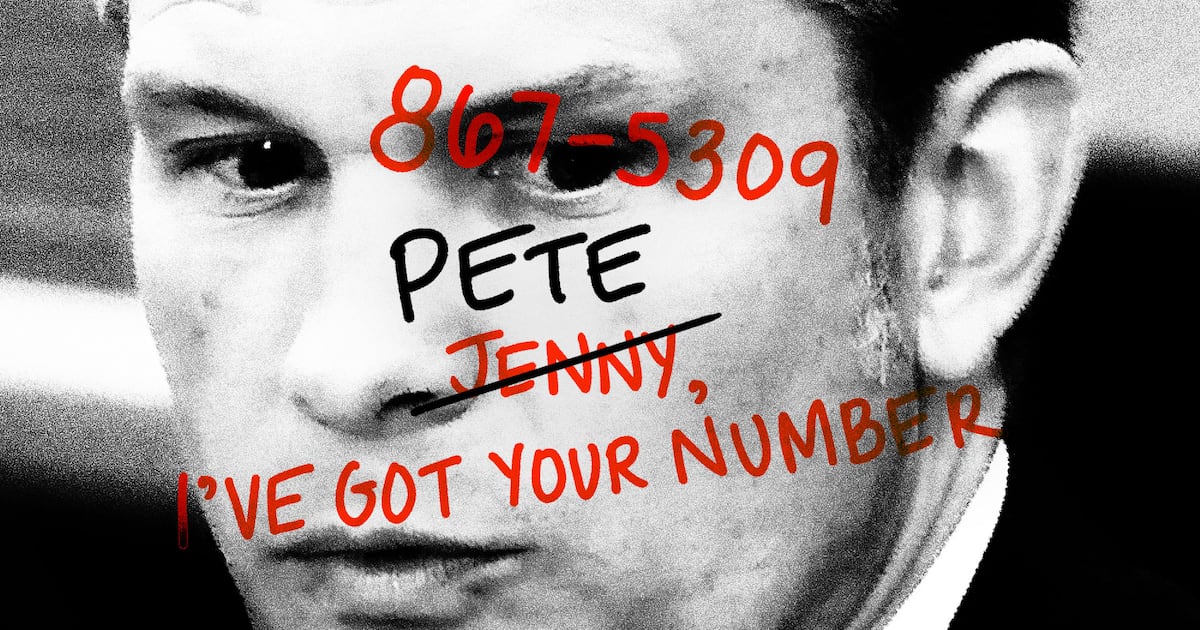

When he was running for president and insisting that America was “a laughing stock,” Trump did not feel his criticism was unpatriotic, nor did he believe it required him to return to the town of Kallstadt, Germany, where his father’s family was born and known by the name of Drumpf. The question is, what’s so special about being a Drumpf that it gives Donald Trump a license to criticize, a license that he denies others?