I witnessed the most compelling sports I’ve seen in months during the fifth episode of The Last Dance, ESPN’s 10-part docuseries about the ‘90s Chicago Bulls, filtered through the team’s eventful ’97-‘98 Season. Before some random mid-season game, we see Michael Jordan challenge a United Center security guard to a strange, improvised game: they would both throw coins from a prescribed distance with the goal of getting the coin as close to the wall as they could without actually hitting the wall. Jordan gives his opponent four tries to his one, on a $20 bet. Jordan throws his coin and steps back, clearing the path for his opponent. A tension grips the audience. Are we about to see Michael Jordan, the greatest basketball player who ever lived, lose a $20 bet with a stadium employee?

The dude manages it in one toss, delivers an iconic shrug to the camera, and we are off and running, back for another evening in the company of Michael Jeffrey Jordan, maniac competitor. It’s pure magic—a normal man triumphing over a living god, the thrill of sports, and a display of Jordan’s monumental, somewhat bizarre competitive drive, all in one strange little story.

There’s been a lot of talk about the inherent value of The Last Dance as a documentary and a journalistic product, and a lot of that criticism is fair. Ken Burns, for one, took umbrage with Jordan’s involvement on the production side of the documentary, and the conditional basis by which the backstage footage from the 1998 season was released to filmmakers, a move that certainly taints the objectivity of the work.

The show makes the team’s late GM Jerry Krause into a convenient villain for his role in the breakup of the championship Bulls after the ‘98 season without observing the broader context of the team, which was ultimately operated by Jordan’s fellow NBA owner Jerry Reinsdorf, who sucks at owning a winning sports team and let the maladroit Krause serve as a meat shield in his never-ending quest to save an extra five bucks at the expense of his squad’s performance. Also, Mike and the documentary try their damnedest to shrug off Gary Payton having MJ’s number in ‘96. Look, we don’t need to act like Chicago wouldn’t have won anyway, but c’mon guys, numbers don’t lie.

But even as a journalistically imperfect enterprise, the element that keeps the series from being a too-neat, Netflix-docu-series-style-half-addictive-bore is Michael Jordan himself. It isn’t just watching him play basketball at the peak of his powers, (although I can’t even imagine how someone could watch him carving up defenses and drilling perfect turnarounds from midrange and not be totally convinced that he is clearly the greatest basketball player who ever lived), it’s the strange, compelling human being you see—the gnarly, rabidly competitive flip side of the unflappable legend who moved on the court like living water, destroyed everything in his path, made himself into the most famous man in the world, was on every commercial you can imagine, and changed sports forever.

There have been flashes of Jordan’s weirdo maladjustment, of course. The Jordan Rules and When Nothing Else Matters, books about Jordan’s time with the Bulls and the Wizards, respectively, are stuffed with anecdotes about his aggressive interpersonal style and his knack for leadership-by-way-of-light-abuse. Jordan’s Basketball Hall of Fame speech is one of the wildest things an athlete has ever put out in the world, a more than 20-minute-long deluge of score settling, resentments, and interpersonal flexing over the bodies of his many vanquished foes. Watching his eyes light up as he recounts personally demolishing Utah Jazz guard Bryon Russell after Russell talked some crap during MJ’s first retirement (the one where he played baseball) is one of the truest delights I’ve been given from sports. His penchant for gambling is well known. But this documentary is the first time when Jordan has consented to sit down and observe and deconstruct that part of himself by his own volition.

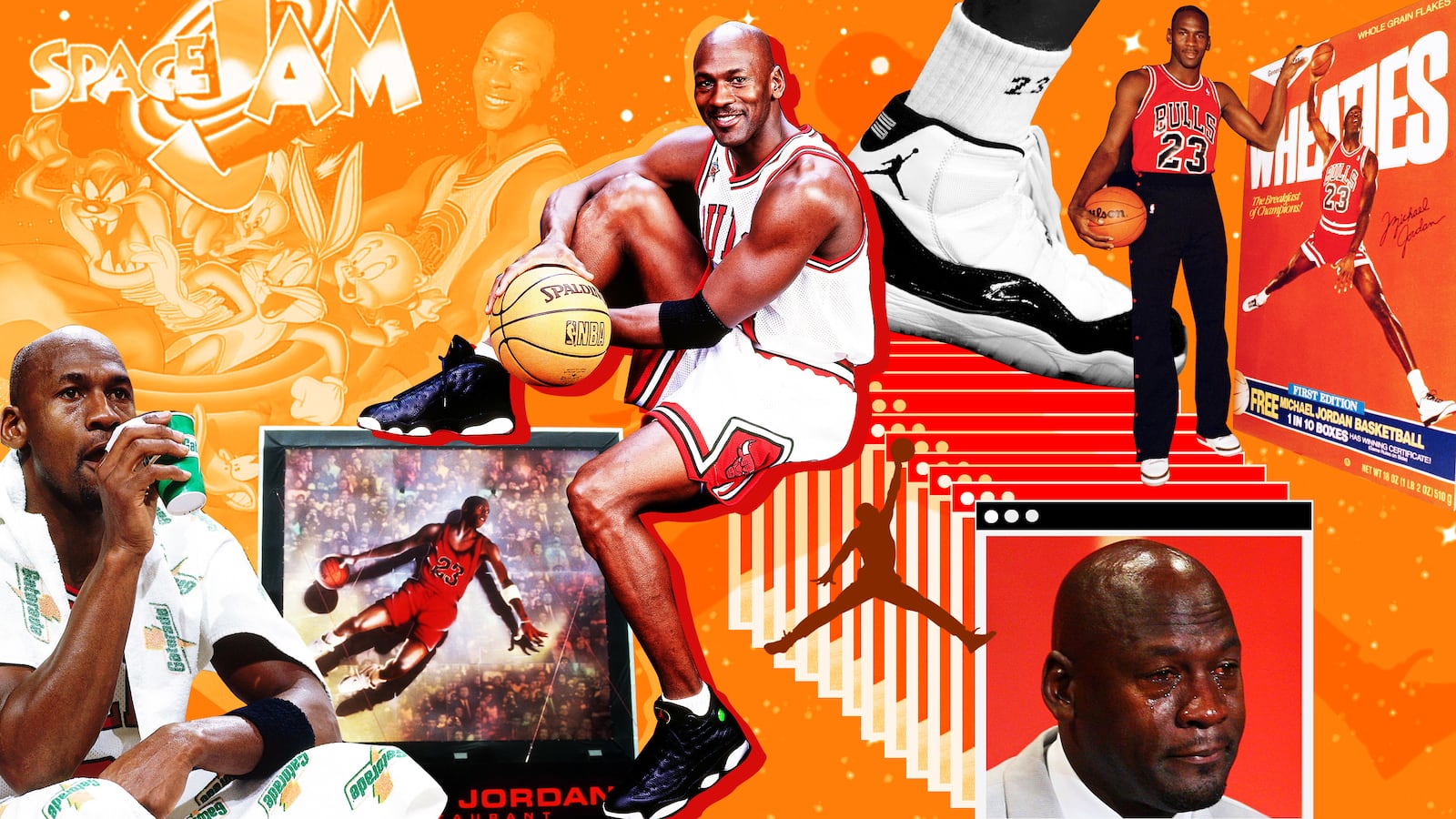

Because, for a very long time, Jordan wasn’t just a basketball genius infected by a personal drive so acidic that it melted carburetors. He was also “MIKE,” pitchman to end all pitchmen, the most famous man on Earth, a worldwide symbol of perfection and resourcefulness that sold shoes by the oceanliner-full and drove people into ecstatic frenzies when they saw him in public and he was incredible at it. Jordan wasn’t just a lunatic competitor, he was also absurdly good at compartmentalization—at maintaining the face he wanted to use at any given time, saving the more unsavory aspects of himself for practices and 3 a.m. blackjack sessions. Jordan in the NBA was a man fighting a war on two fronts: against his opponents and against the competitive beast inside, and just dominating on both fronts. It’s no wonder that modern NBA stars sometimes seem like they’re teetering on the edge of sanity—the example Jordan set is basically impossible to live up to if you’re anything short of a complete megafreak with a brain made of steel.

Watching The Last Dance, you see the man as a whole. Archival footage heaping abuse on Jerry Krause right before a game. Will Perdue regaling the audience with a story about MJ stepping away from a $10,000-per-pot poker game with Scottie Pippen and the other high rollers, sidling up to his and John Paxson’s $1-a-pot blackjack game and tossing his hat in just so he can walk around with the knowledge that he took their money. Archival footage from the Bulls’ 1997-98 season shows Jordan just unloading shovelful after shovelful of verbal abuse on anyone he can in practice, a one-man hostile work environment.

We see the man in the present-day, getting interviewed for the documentary, either tossing back tequila or wearing an insane pair of pink camouflage shorts, clearly still annoyed about Pippen having to sit out with a migraine during the Bulls’ 1990 series against the Detroit Pistons. He dubs his early teams a “traveling cocaine circus,” shrugs his shoulders about his gambling exploits, declares his love of high-stakes games of chance a “hobby,” and delivers the immortal (and also pretty much correct) line: “I don’t have a gambling problem, I have a competition problem.”

Compare this unleashed heap of id to the Jordan we see in Spike Lee’s iconic Mars Blackmon commercials. Cool. Collected. Straight man to an antsy basketball nerd. The essence of relaxed, self-contained excellence.

Here he is in a commercial for Michael Jordan cologne (“Top notes are cypress, cognac, grapefruit, cedar needles, Brazilian rosewood, geranium and lemon; middle notes are juniper berries, lavender, fir, green tea, clary sage, cloves and incense; base notes are sandalwood, patchouli and musk,” according to Fragrantica.com), shirtless and in an intimate moment, casually shaving his head while still exuding subtle sex appeal and looking like a god. Make no mistake: Jordan was a figure of extraordinary cultural horniness.

Jordan was frequently paired with Bugs Bunny—not only in Space Jam, but in commercials. It’s a canny pairing, I think. People might, somewhere off in the future, think of Jordan as merely an icon, the NBA’s Mickey Mouse. But even before people knew he was the kind of dude who would call the centers he played with “21 feet of shit,” people saw that he was more dangerous than that; a force of nature you shouldn’t fuck with. In the same way that Bugs Bunny cons Daffy Duck into giving Elmer Fudd his own letter of execution, so did Jordan outfox the Pistons, the Knicks, the Jazz, the Trail Blazers, the Cavs and whatever hapless defenders they happened to send his way. The public was sold a dude who was supremely confident and wily, but not… demonstrative. Subtle.

Contrast the narrative they used to sell Jordan with the one they threw out there for Barkley.

Here he is in an animated Nike ad, all scribbles and lines, crushing everyone under the weight of his raw power, gearing up to demolish Godzilla in one-on-one, an unstoppable force of nature on the court. Less Bugs Bunny than Tasmanian Devil. Over the years, we’ve seen that these depictions aren’t as apt as they seemed to be. Barkley, of course, is actually an extraordinarily friendly man, the sort of dude who strikes up lifelong friendships with guys he meets at airport bars, while Jordan is, well… a tornado who wields his excellence like a chainsaw and leaves a trail of destruction in his wake, feelings be damned.

Even Jordan’s most neurotic moment got laughed off by dint of his extraordinary presence. After he retired from the NBA for the first time, sick and tired of the nonstop pressure of being the most famous person in the world, went off to play Double-A ball in the Chicago White Sox system, didn’t do all that well, and then came back 18 months later, it didn’t really read like a freakout, like it would if, say, LeBron James did it. It was played more like a moment of searching, a reasonable reaction to the psychosis of his public life.

One Gatorade commercial went as far as to depict Jordan’s self-imposed exile as a journey of spiritual searching. Even when he left the game he dominated to go fail at baseball, he was Teflon—Bugs Bunny missing the left turn at Albuquerque, not a dude acting out in the midst of a profound crisis after the death of his beloved father.

After the Bulls won 72 Games and the title in ‘96, as his time with the Bulls was clearly coming to an end, the way Jordan is depicted in ads subtly shifts. He isn’t a perfect human anymore. He is transformed into a god, an event, a silent icon of perfection. He even did a commercial with Muhammad Ali. This is the Jordan we internalized after his retirement: totally untouchable, the kind of guy who has so much juice that he takes a stab at reclaiming Hitler’s mustache in a Hanes commercial.

Which one is the real Michael Jordan? It’s tempting to give full credence to the version we’re seeing in The Last Dance, the cranky perfectionist who lives for the juice of absurdly high stakes, hashing his old beefs and re-declaring his personal loathing for Isiah Thomas (which Thomas definitely earned, having lived his entire life as an asshole), but I think the fact is that the man’s inner Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck are both valid entities, a walking neurosis that fed his excellence and an excellence that validated his neuroses. Seeing them crash against each other, the man’s blood and black bile fighting for dominance even in his twilight, has been, at the very least, fascinating television.