What is striking about On The Inside, a group art show of works by LGBTQ prisoners at the Abrons Arts Centre on New York’s Lower East Side, is how tender, even romantic, the images are.

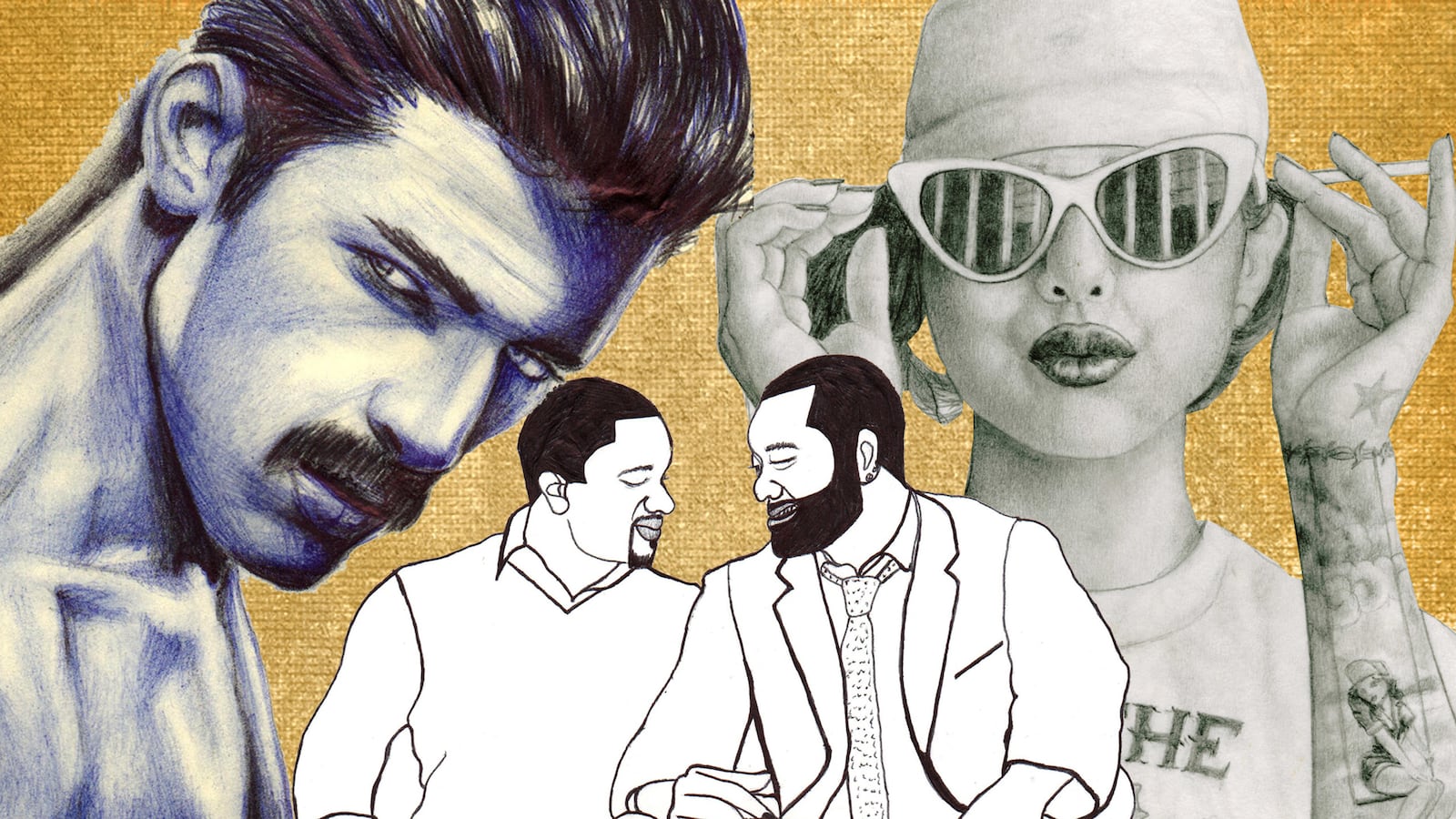

There are few images of incarceration or suffering, and instead many images of magical fairies, gender-blurring beauties, muscular bodies, love, sexiness, warriors, prayer, figures of faith, and iconic heroes. 4,000 images were submitted from LGBTQ prisoners all over the US, with 450 selected for the final show.

Around these images are printed the writings of the prisoners who created the art sent in letters alongside their works to exhibition curator Tatiana von Fürstenberg (full disclosure: she is the daughter of Diane von Fürstenberg, who is married to Barry Diller, chairman of IAC, which owns the Daily Beast). Von Fürstenberg made a donation for each work of art to the participants; their first names or initials are attached to the works.

Some images are simple, others more elaborate and colorful. The images were created mostly on letter-sized paper, using dull pencils, and ball-point pen ink tubes (the hard shell is deemed too dangerous). One picture of a line-up of prisoners features a woman among the men; a sea of faces is broken by the presence of a nude body held aloft; a gorgeous, muscular body has a non-gender specific face; Bruce B.’s ‘The Wandering Mind’ features a woman in repose; James L.’s features a spotlit owl.

As you linger over the images, the captions--which provide a moving snapshot of the added layer of harassment, prejudice, and discrimination LGBTQ inmates experience when incarcerated--prove piercing.

“One of the male guards liked to sit four feet away and watch me shave my body and shower when he was on duty,” writes Paula W. “He’d ask me what I would do for him if I asked him for anything. Another guard that escorted me to the doctor’s office said, ‘I bet you enjoyed that’ after my prostate exam.’”

“I have been stripped of all my property, clothing, mat, and left to sleep on a steel bunk in 30-degree weather,” writes Felicity. “I’ve been harassed time and time again for my identity, being a flamboyant fem gay. But still I stand, I won’t bend and I won’t break. I am proud of who I am, I carry myself with gay pride 24/7.”

“I just can’t understand why our proud American culture is accepting of our inhumane, undignified prison system,” writes Tony W. “It is insane to treat people horribly for years, then return them to society. I’ve become wise, yet pissed off.”

“I’m a happy gay man, but have a lot of problems with other inmates so I lose myself in drawing,” writes Ronnie S.

“I have been locked up for the past 23 years,” writes Jimmy W. “I told my brothers and sisters that I was gay, and till this day I have yet to receive mail from them. But I feel great and love myself.”

Not all is grim. “I had several relationships in prison and had the best sex I can possibly imagine,” writes Cheyenne. “My favorite part of the day was lockdown. We would make out until the count, that’s when the real fun started.”

One image features a heavily muscled guy holding another slighter guy: “Familiar acts are beautiful through love,” its caption reads. A set of portraits include nudes, Nelson Mandela, a couple holding one another, fairies and humans with butterfly wings. There are hunks in leather and a self-explanatory picture entitled, ‘Gay Pandas Fucking,’ and then a stunning portrait of a beautiful, bearded man.

“Inside and outside prison walls, art has always been the freedom only a higher being can bring,” writes Yenniel H. “My mind, hands and pencil combine to express something greater than myself.”

A religious section includes images of God, Jesus and the Virgin Mary, and a caption by Ziva: “I used to think that prayer was sorta stupid, praying to someone you can’t even see. But now after experiencing it I see why people get on their knees to do it.”

Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, and Abraham Lincoln feature on a wall of heroes, alongside superheroes, and then in a central blocked-off area, the size of a solitary confinement room, even more explicit images of penises and vaginas.

Sitting inside this solitary confinement room, von Fürstenberg reveals how she compiled the show over almost five years. She made contact with the prisoners through the LGBTQ prisoner support organization, Black and Pink, which she describes as “like a family, a wonderful organization.”

The results of a survey of LGBTQ prisoners’ experiences conducted by Black and Pink—around issues including parole and gender and sexual identity--are printed on the walls of the ‘solitary confinement’ room.

The 46-year-old Von Fürstenberg said the idea for the show came as she was beginning a 30-day period, each day performing “a pledge of love.” Her idea, to have a prisoner pen-pal, became the seed of the exhibition when her online research led her to the Black and Pink website.

The long gestation of the show, she says, was ideal as she suffers from a debilitating muscle condition, Myotonia congenita, and has done since she was a young girl. The nature of this—von Fürstenberg has just suffered an excruciating “flare-up,” which led to her mother buying her a scooter so she could work on setting up the show—means she must conserve her energy, and work at her own speed.

“It’s the inability to relax,” she says of her experience of the condition. “It’s a decreased ability to relax out of contraction. If I sneeze I can’t open my eyes. If I use my strength, my muscles jam and lock. My muscles are always damaged, and I have an inability to recover from damaged muscles. But my muscles are always getting damaged, so I’m in a lot of pain. Everything hurts.”

Von Fürstenberg grew up in New York, the daughter of Diane and her first husband Prince Egon of Fürstenberg, which makes her a princess-in-name. She is extremely down-to-earth, intensely thoughtful and committed to her work, and dressed in light, casual clothes deliberately chosen so as not to hang heavily on her body. She is close to her older brother Alexander (“we’re connected, we’re both Aquarians”), born the year before her.

Suffering from the muscle condition all her life has made von Fürstenberg reflect on how “biology informs one’s identity. One reason I relate to this show is that I believe biology informs one’s entire personality. I never played as a kid. I couldn’t. I always had to be in a seated position observing, reflecting. I did really well at school. I got into Brown University at 16. I generated ideas, stories, because I never participated in any physical activity whatsoever.

“I felt like an outsider. As a disabled woman, I feel marginalized. I don't have fear of mortality. When you live with chronic illness you imagine a release. I want to be alive, but I don't want to be in pain. The pain is really intense.”

It must have been strange to grow up, feeling like that, in the whirl of fashion and the fashionable, I say.

“It was really weird,” von Fürstenberg says. “I can’t actually wear the clothes, but more than that I can’t relate to the aspirational-woman model. I have to emerge from within because my limitations make me. I can’t decide to be ‘something’ and chase that, because it doesn’t work for me.”

Her family has been supportive, she says.

“My mom has learned a lot from me and I think I have been her teacher in a lot of ways. She really gets me, she can tap in to it. We’re super-close and she’s super-respectful of me. She can feel me. With the scooter, she’s such a savior. I’m usually bedridden for a few days when I’m in crisis, which is very isolating. This will really help me. Next time I’m in crisis, which happens quite frequently, I’ll use it.”

Von Fürstenberg wasn’t diagnosed with Myotonia congenita until she was 21. “I overcompensated a lot as a kid. I really struggled to keep up. It was thought I was acting up, different, eccentric, my teachers thought I was rebellious. I really wasn’t. I was late getting to class because of my condition.

“My grandmother lived at home with us. She was a Holocaust survivor, and had osteoporosis resulting from malnutrition. She didn’t know why I liked lying on her bed with her and talking, so I did have company. She was very bright and encouraged me in psychological, philosophical, and critical thinking.”

The diagnosis wasn’t just a relief, it meant she could teach “myself not to teach myself to hurt myself to keep up with those who were able-bodied. I don't like to look in mirrors. My physical body holds me down. I kind of like to deny it. I connect to my heart and mind.”

She didn't know “going to beach could be fun until really recently because I used to go to hold everyone’s shoes and bags. It’s really hard to grow up different.”

However, she insists she is no "tragic figure." Her personal transformation, as von Fürstenberg puts it, began six years ago when she began writing. Her parents were creative, and her 16-year-old daughter Antonia has applied to go to art school.

As a parent, suffering as she was and unable to do what most parents do with their children, von Fürstenberg found honesty with Antonia was best. “I had strict boundaries because of my limitations.” As a result, Antonia is “very compassionate and thoughtful, and independent.”

Von Fürstenberg describes her own sexuality as “fluid.” At the end of her college years she fell in love with film-maker Francesca Gregorini, who she later made the film Tanner Hall with. Von Fürstenberg was with Antonia’s father, actor and writer Russell Steinberg, for eleven years.

She is single at the moment, and focused on her "wellness." Living in Los Feliz in Los Angeles, she is happy to be surrounded by loved ones and friends.

“My dad was gay,” she says. “He had a lot of internalized homophobia early on, and had a really hard time coming out to me initially. He got better with it. Growing up in the fashion world meant I was basically raised by the LGBTQ community entirely. They were the only people I could really relate to.”

She recalls being 8 and 9, “during the dark days of the AIDS epidemic. I saw everybody getting sick and I was young. I lost a lot of friends. That completely traumatized me. People were whispering things behind my back, not telling me because I was a kid. I wanted to offer my love but I wasn't allowed to.

“I saw so much shame. I saw so much hiding: the dyeing of hair, the wearing of suits, changing your look not to disclose your status, a façade--and to have that internalized shame of being ill and I think I internalized the shame of being ill too.” She pauses. “That was an epidemic, and there is also a hidden epidemic of LGBTQ prisoners.”

The isolation von Fürstenberg felt because of her illness means she identifies strongly with the experiences of the prisoners whose work she has curated.

She talks about “the kid who hadn’t come out to his family messing around with a guy in what turned out to be a stolen car. He was arrested, and called his mom, who he hasn’t heard from since. Another trans woman has been for years, without even having a trial.

“The misconception created by the media is to make everyone in jail seem really dangerous, when in fact the prison population would be massively reduced if they decriminalized sex work, or stopped arresting under-18s, or stopped jailing people for the technical violations of probation. A lot of crime is poverty-incited.” Von Fürstenberg decries those agencies and businesses who financially profit from incarceration.

The 4,000 works of art came in spurts over the last few years, von Fürstenberg says. She was struck by the “feeling of worthlessness expressed in the letters, being forgotten, not mattering. The other side is, through this show, being remembered. The exhibition, having their work shown, their work being wanted, restored their faith in humanity. I don’t want people to think of this as ‘outsider art’ though. These are artists who are currently incarcerated. Think of it otherwise and it becomes horribly exploitative.”

After the show, von Fürstenberg plans to continue working on her autobiographical graphic novel, My Summer, Unapologetic, set when she was a teenager wrestling with her disability, and on holiday with her dad and brother in the Mediterranean. “It’s a coming of age tale for all of us: my dad comes out in it, and my family breaks up and comes back together.” (Her father died in 2004, aged 57, of complications arising from liver cirrhosis and Hepatitis C, she says; she does not know if he was HIV positive.)

Von Fürstenberg and I finish our talk by surveying the pictures of celebrities prisoners have submitted. They include images of Marilyn Monroe (made ingeniously from Kool-Aid and an asthma inhaler), Michael Jackson, Robin Williams, and a set of particularly memorable images of Rihanna. (Hurrah, no Kardashians.) They’re figures who have fought back, been persecuted, survived or endured demons, says von Fürstenberg: “They are vulnerable and assertive.”

“Michael Jackson was so misunderstood, so I drew him because I understood,” writes Marvin D.

Surveying the art, von Fürstenberg says exhibition visitors will be able to send text messages to the prisoners whose work is on show. “What I hope is that people realize the enormous amount of talent, complexity, and culture of LGBTQ people within prison. You can’t stereotype and forget them. I want people to be wowed by the quality of the work, and the voices of these people to be heard.”

Before I leave, I read two more of the artists’ captions.

“As a gay child I was accepted openly by my grandparents, writes Christopher R. “It’s a shame not everyone is accepted for who they are.”

“It shouldn’t matter if society doesn’t accept us,” writes Joseph B. “Who are they to judge and look down upon us? They are no better than us—the same God that put them here, put us here too. Now I am open about my sexuality, and I encourage you to do the same and experience true freedom. If no one told you that they love you, I am telling that I love you, OK?”

On The Inside is on show at the Abrons Arts Centre, 466 Grand St, New York, NY 10002, until December 18.