The scandal embroiling Brett McGurk, the Obama administration’s nominee to become the next ambassador to Iraq, got its start when an anonymous tipster alerted a 76-year-old architect to recent photo uploads on a mysterious Flickr account. The account contained what purported to be images of explicit emails from 2008 between McGurk and Gina Chon, then a Wall Street Journal correspondent in Iraq.

In the wake of the leaked emails, Chon has resigned from the Journal, McGurk’s nomination is imperiled, and media pundits have had a field day debating whether an email discussion of “blue balls” between a reporter and her source is unethical or merely stupid.

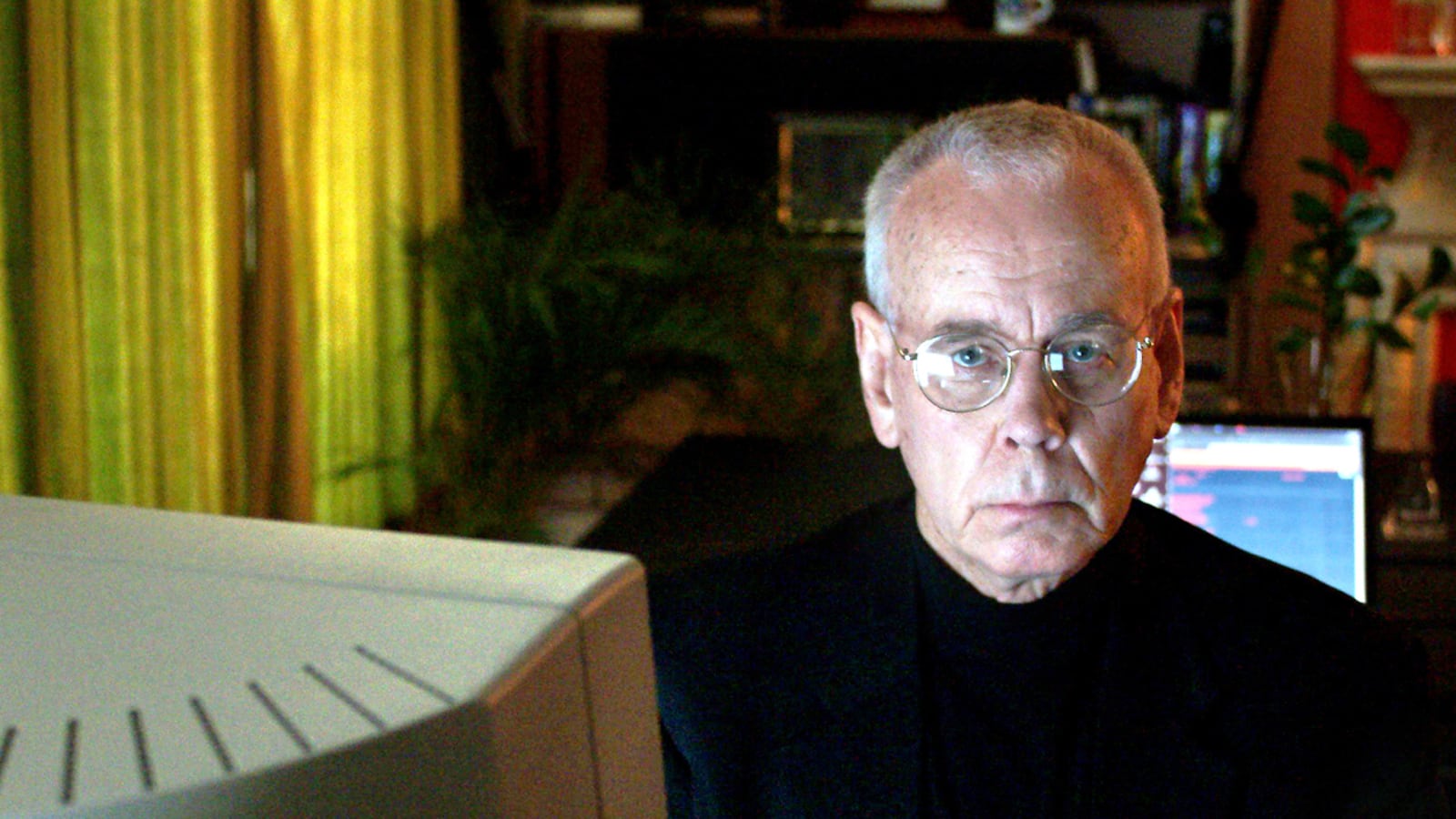

But what’s received less attention is the website that published those emails, and the man who runs it. John Young founded Cryptome, a clearinghouse for leaked documents from the military and intelligence community, in 1996, roughly a decade before WikiLeaks existed. It has since become a must-read for some people who track the intelligence community and the military. “Cryptome has become part of the national security information landscape,” says Steven Aftergood, the director of the project on government secrecy at the Federation of American Scientists, a nonprofit think tank. “I check it every day,” he adds.

Over the years, Cryptome has published lists of names it claimed were MI6 officers and Japanese intelligence officers, photos of sensitive U.S. installations, and satellite images of the homes of top intelligence officials, including former CIA director Michael Hayden. It’s one of a handful of esoteric sites, with names like Public Intelligence and Cryptocomb, vying to be the first to leak sensitive information and attain the kind of notoriety WikiLeaks won after its 2010 publication of U.S. State Department diplomatic cables. Hayden declined to comment.

“There are hundreds of other people doing the same thing [as WikiLeaks] and they don’t get the same attention,” says Cryptome’s Young. “We think the secrecy has been overdone,” he adds. “It’s gotten way out of hand and there is insufficient accountability. There needs to be more openness and accountability. It has divided the world between those who have access to secrets and those don’t.”

Cryptome, which Young runs with his partner, Deborah Natsios, began as an outgrowth of an electronic mailing list popular in the first years of the public Internet. Known as Cypherpunk, the list brought together people to discuss ways to encrypt electronic messages online and thereby shield communications from government eavesdroppers like the National Security Agency.

For a guy in the business of publishing other people’s secrets, Young is circumspect about his own personal life, offering few details about his wife and children or examples of his architectural work.

A defense contractor who works to protect the military’s classified computer networks said Cryptome is known inside the classified world of government cyber-security for things like publishing “satellite photographs of facilities the government does not want you to see.” But, adds the contractor, “I don’t see them as a threat to national security in the same way that state-sponsored hackers are a threat.”

Aftergood, of the Federation of American Scientists, says Young is “fearless and contemptuous of any pretensions to authority” and “oblivious to the security concerns that are the preconditions of a working democracy. And he seems indifferent to the human costs of involuntary disclosure of personal information.” For example, says Aftergood, “it’s fine to oppose McGurk or anyone else. It wasn’t necessary to humiliate them.”

Young says he often gets “accused of going too far. I say to Steven Aftergood, ‘You bet we go too far, because you don’t go far enough.’”

He says that because the McGurk emails were from the State Department, they counted as government information and were thus fair game for publication. In addition, he says, the emails show McGurk himself breaching security, so it was in the public’s interest to expose them in light of his nomination.

Young says he expects more McGurk emails to surface. “It looks like the opening shot of a campaign and it seems to be working,” he says. “Planting these things in out-of-the-way places to let them slowly simmer is how it’s done.”