It was the work of a lifetime, an evolving masterpiece created over 10 years.

One can imagine the day in the early 1920s when German artist Kurt Schwitters, maybe while taking a break from crafting his distinctive collages and sculptural assemblages, looked around his home and realized he was living in the biggest canvas of all. And so the work he would dedicate the rest of his life to, the ‘Merzbau,’ began.

Then with the high-pierced whistle of an Allied bomb in 1943, his Hanover masterpiece-cum-family home was reduced to rubble.

Schwitters’ ‘Merzbau’ was the embodiment of his artistic philosophy, a living sculpture in which he brought together disparate ideas and discarded objects to create something beautiful.

Even after he was labeled a degenerate and forced to flee Germany on the cusp of WWII, he continued his mission, creating new iterations of the Merzbau first in Norway, then England.

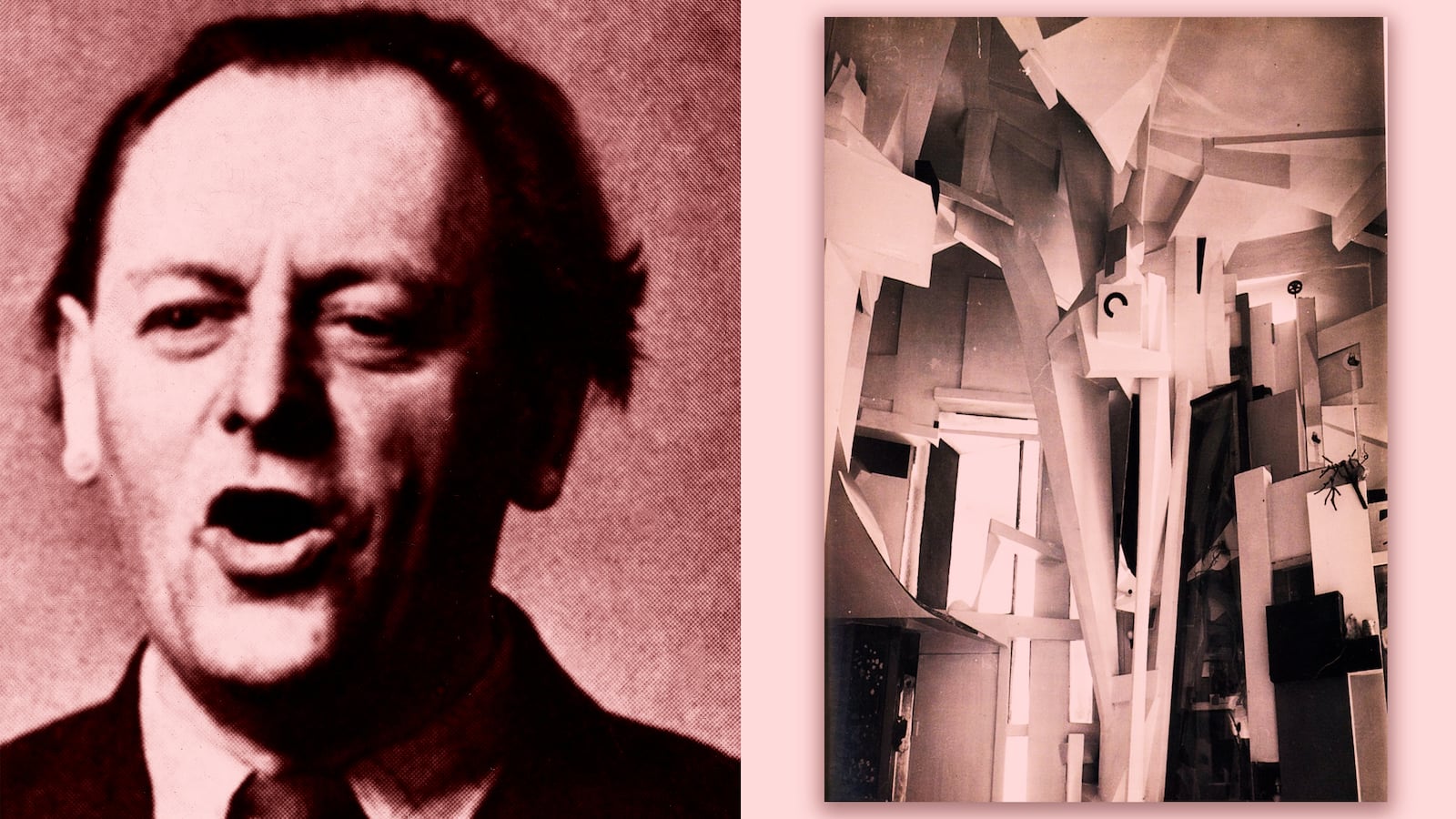

The former was destroyed in a fire, the latter left incomplete on his death. In the end, all that remains of his original masterpiece is a handful of black-and-white photos that look like abstract works of art in their own right.

Schwitters began his artistic career on the more traditional painterly path. But like all who lived through the 1910s, he emerged from the destruction of the Great War a changed artist.

He began to collect things he found on the streets—bits of trash and abandoned objects—and he combined these scraps into works of art. First, he began to assemble collages and then his work began to gain sculptural depth. Out of the ashes of war and discarded, seemingly disparate objects, Schwitters was creating something new and innovative.

“Schwitters made these collages in the wake of the First World War as hopeful portraits of how destruction can feed creation: how bits of advertising, scraps of newspaper, wood, garbage, and urban debris could all be collaged together into something new and beautiful,” Elisabeth Thomas, assistant archivist at the Museum of Modern Art, wrote in a post for the museum.

His ideas were fresh and exciting, and they helped bring him to the attention of the German art establishment. He was part Expressionist, part Dadaist, but, as the legions of pioneers who came before him knew all too well, being on the cutting edge—not to mention torn between two camps—doesn’t ensure you a place in their ranks.

After being rejected by the Berlin Dadaists, Schwitters retired to his family home in Hanover and developed his own movement that he crowned with a nonsense word—‘merz.’

Derived from “Commerz Bank,” which was written on a scrap of paper Schwitters once found, ‘merz’ was the word the artist used to describe his artistic style, his aesthetic, and even his way of life. ‘Merz’ was Schwitters’s all-encompassing philosophy.

“‘Merz’ means to create connections, preferably between everything in this world,” Schwitters said.

Or, as Thomas puts it: “Schwitters’ art was more than just the collage object itself. It was a whole process, philosophy, and lifestyle… He was a merz-artist who made merz-paintings and merz-drawings, and naturally, the place where he merzed—his studio and family home—was his merz-building, or Merzbau.”

It was in 1923 that Schwitters first began turning his family home and studio at 5 Waldhausenstrasse in Hanover, Germany, into a work of art. Originally called “The Cathedral of Erotic Misery,” Schwitters took his principle of merz and began to apply it to first one room, then another.

Writing in the Journal of Architectural Education, Kendra Scott explains that the project began after Schwitters first merzed in his home, noticing connections between paintings that were hanging on his wall. So, with a piece of string, he made that connection tangible, linking one canvas to the other. Then he began to attach some of his found objects and scraps directly to his walls.

This early work on the ‘Merzbau’ grew ever more plentiful until entire rooms had been transformed into works of art, including individual grottos that popped-up as pieces within the larger composition. He used objects he discovered on the street, works of art and knick knacks given to him by friends, and even substances not normally considered viable materials—think ashes, tears, and urine.

“Like The Waste Land, the ‘Merzbau’ critiqued the alienating conditions of modern technological culture; it also provided a haven from the chaos of the outside world,” Scott writes. “As it developed, the ‘Merzbau’ took on an organic, almost vegetal pattern of growth that engulfed his home and life.”

In 1927, a fellow German painter Rudolph Jahns described his experience visiting the ‘Merzbau’: “I entered the site, which resembled with its many turns both a snail-shell and a cave. The path leading to the center was very narrow, since new sections and constructions, together with the already existing Merz-reliefs and caves, grew into the empty space. Immediately to the left of the entryway hung a bottle with Schwitters’ urine in which floated Immortelles. Then came grottos of different types and sizes, whose entries were not always on the same level… I was overcome by a strange sensation of rapture.”

Schwitters was avant-garde at its most extreme, so its perhaps no surprise that he attracted the unwanted attention of Hitler and his early crusade against all things modern. Labeled one of the “degenerate” artists and included in the infamous exhibition in Munich, Schwitters was forced to flee his home in 1937.

Leaving ‘Merzbau’ was a no-doubt devastating turn of events for the artist, but his great masterpiece represented more than just a home; it was a philosophy and philosophies travel.

“Schwitters’ aim can be surmised by the fact that he started his Merzbau again and again at the different locations where he lived… carrying it around him like a snail-shell,” Karin Orchard wrote for Tate.

Schwitters first went to Norway, where he attempted to recreate his merz-home. In 1940, he had to run once more and he landed in England. There, he received funding from the Museum of Modern Art in New York to start over again, but his death in 1948 cut the project short. In 1943, a British bomb had reduced his original ‘Merzbau’ to dust; in 1951, the Norway ‘Merzbau’ burned down.

While all that may remain of his grand masterpiece are a few black-and-white photographs of his original ‘Merzbau’ taken before his exile, and bits and pieces of his final attempt housed at Newcastle University, Schwitters’ philosophy has lived on.

Over the ensuing decades, his legacy has grown and his work has influenced a wide-ranging group of artists from David Bowie to Jasper Johns. An equally wide-ranging group, from the stage designer Peter Bissegger to the famed architect Zaha Hadid, have made plans with varying degrees of success to recreate his crowning achievement—the ‘Merzbau.’

To this day, Schwitters’ work and ideas remain relevant. While the Dadaists may have had their moment, the questions posed by ‘merz’ are eternal.

As Michael Glover wrote in The Independent: “Schwitters wanted his art to be seen as a total endeavour, the bombing of entire cultural neighborhoods with merz and yet more merz. The work is full of a cranky, self-conscious humor. It is always calling attention to the fact that it is part of an ongoing engagement with art-making—which makes us question, of course, what exactly art-making is, has been, and is supposed to be. It poses all these questions all at once.”