What would Derek Jarman have made of Apple CEO Tim Cook’s coming out, of full legal LGBT equality in his home country of Britain? Of gays being persecuted viciously in countries like Russia and Iran?

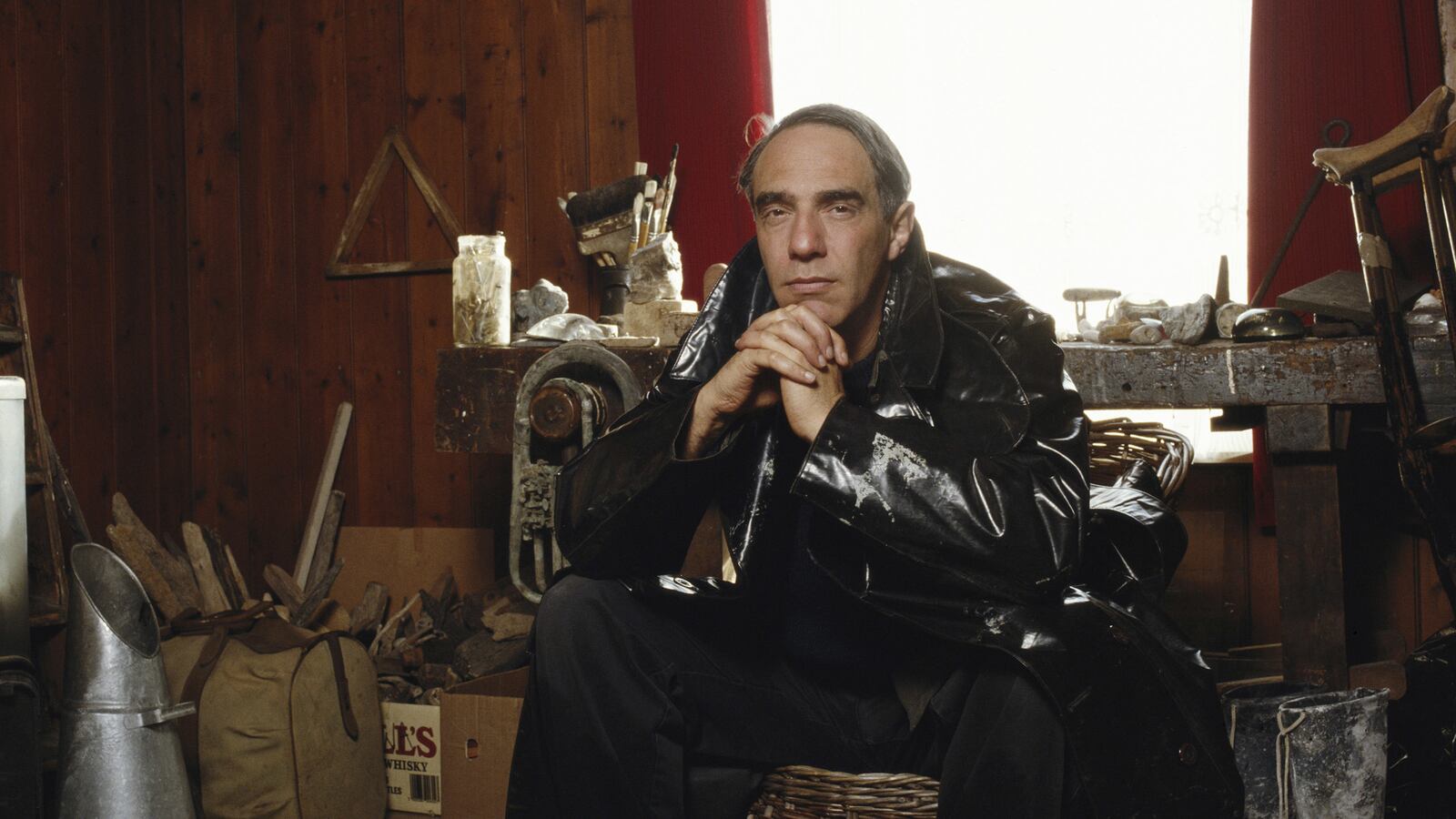

As a season of his films opens at New York’s BAM, I remember how charged the death of the visionary filmmaker, pop video maker, artist, and activist was 20 years ago.

Jarman died of AIDS, aged 52, in February 1994, the night before a historic vote in Parliament to equalize the age of consent for gay and straight people at 16. At the time the straight age of consent was 16, and it was 21 for gay men.

Jarman was a passionate, angry, eloquent campaigner for equality and social justice, identified strongly as “queer,” and was a member of the veteran activist Peter Tatchell’s direct action group, Outrage.

Jarman didn’t live to see the result of that 1994 age of consent vote, which rejected equality, voting instead to lower the gay age of consent to 18. Jarman’s death had made an already emotional night that much more emotional. (It wasn’t until 2001 that the age of consent was finally equalized.)

Speaking to The Daily Beast, Jarman’s friend Paul Burston, the journalist, novelist, and founder of London’s Polari literary salon, recalls: “There was a vigil outside, with people lighting candles. When the vote was announced and people were informed that MPs had voted against gay equality, there was a riot. Some people even stormed the building. Derek would have loved that.”

Jarman’s film season at BAM is titled “Queer Pagan Punk,” and I suspect—regardless of today’s social and legal advances—Jarman would have still questioned how accepting society had become, how ready it was to accept and show the full range of LGBT sexuality.

His varied projects were steeped in raw, passionate sexuality, passion, wit, high art, mischief, and also the view of a world viewed sideways. The real-world rush to codify gay marriage probably would have raised Jarman’s hackles, as much as he would have welcomes a more equal world. He wasn’t anti-assimilationist for posing’s sake, he was a natural renegade: queer in every sense of that word.

In a beautiful Guardian essay, the writer and director Neil Bartlett rightly said Jarman was very of his time—the scrappy London of Jubilee is barely recognizable next to the glossy condos of today—yet the beauty and universality of his art endures.

“He would have welcomed the gay equality that came eventually but he would have always needled for more,” his agent Tony Peake once told me. “He grew up in the 1950s and 1960s when homosexuality was criminalized, and those scars go deep.”

Jarman’s films are, as you’ll discover at BAM, stunning. He was an artist (his later canvases are furious, kinetic expressions of anger and passion), and his films are notable for their beautiful, painterly compositions. They are variously loud, meditative, dramatic, witty, sexy, searing, and elegiac.

Jarman was also a natural rebel and renegade, and so in Jubilee (1977), his imagined adventures of the queen, adrift among “anarcho-freaks,” unfold alongside the punk music of the time—including Siouxsie and The Banshees, and The Slits.

This weekend, you can see his evocative adaptation of The Tempest (1979), as well as Edward II (1992), which the Jarman movie season’s curator, Nellie Killian, says broke through in the United States around the same time as the “New Queer Cinema” of directors like Gus Van Sant (My Own Private Idaho). It is a charged, witty mix of historical tale (Edward II, the 13th century British king, was reputedly infatuated with another man) and modern-dressed romp, replete with hot sex and gay rights protesters.

Jarman not only evoked on screen but wrote about his exuberant love of sex, and the “fraternity” of men in that famous cruising location Hampstead Heath, in his books and memoirs: Modern Nature, At Your Own Risk: A Saint’s Testament, Dancing Ledge, Smiling in Slow Motion, and Chroma.

Other Jarman films showing at BAM include The Last of England, Caravaggio (a seductively beautiful film about the painter, starring the then not-famous but still commanding Tilda Swinton), The Garden, Wittgenstein, and the stunning Blue, which evokes—with just a blue screen and astonishing soundscape—Jarman’s condition as he lost his sight.

Burston says Jarman “had an enormous impact—not just on gay culture but on popular culture and on the worlds of art and politics. There were the films, of course. Very few British filmmakers made such extraordinary films on such small budgets, or fostered such diverse talents as Tilda Swinton and Sean Bean. But there were also the diaries, the pop videos he directed for bands like Pet Shop Boys and The Smiths, the paintings, and of course the activism. He was very political and driven by a strong sense of injustice.”

Jarman, says Burston, “was queer long before it became fashionable. He wasn’t a fan of the softly-softly approach to gay politics. He was angry, and he found it hard to understand anyone who wasn’t. He once said that if you weren’t angry, you couldn’t be living very hard. When he wrote an open letter to Ian McKellen, saying he was wrong to accept a knighthood from a government which had introduced Section 28 [a Thatcher-era law that forbid the promotion of homosexuality], he really set the cat amongst the pigeons.”

There was, recalls Burston, a letter to the Guardian, signed by various gays great and good, denouncing Jarman for daring to rock the boat. “But you have to bear in mind that gay life in Britain was very different then,” says Burston. “The age of consent for gay men was 21, compared to 16 for heterosexuals. We had no employment rights and no partnership rights. Combination therapies hadn’t arrived yet.”

Gay men with HIV/AIDS were “dying all around us,” he says. “There was a lot to be angry about. And at the time he wrote that letter, Derek was also conscious of his own mortality. Being public about his HIV status was incredibly brave, and he was monstered by the press. HIV had a huge impact on him.

“He was a fighter, and he became furiously energized by it. No time was wasted. His output during those last few years was astounding—books, films, exhibitions of his paintings, and the extraordinary garden he created at Dungeness.”

“Dungeness” meant Jarman’s home near a huge power station in Kent, a seemingly inhospitable place where he crafted the most amazing garden, which people (including me) would visit.

Swinton, who starred in six of his movies, once told me Jarman was, “for us young ones just moved to London from university or homes in the provinces, the greatest fun grown-up you can imagine being around. He wore his renegade identity like a buccaneer’s cape: lightly and with gleeful pride—in fact, a proper swagger—and he made it his business to be inclusive.

“He spun a party out of every production meeting, every shoot day, every elevenses. What I remember most vividly about living alongside him for nine years, after all the paper parades and balloons on sticks, was the peaceable-ness of our pootling about in silence at Dungeness in the garden, on the beach, in his studio, for hours at a time. He was above all a fine—quiet—companion. I miss him very much more for this reason than any other.”

Ken Russell, the now sadly deceased British film director, told me he considered Jarman a visionary. “Who else could have convinced me to update Stravinsky’s opera The Rake’s Progress from Hogarth’s time to the time of the Falklands conflict, with Margaret Thatcher as the sexy madam of a swish London brothel?” he said. “But apart from being an ideas man, he was a practical one, as well—you only have to look at the 20-foot Easter Island primitive head in my film Savage Messiah, that he carved single-handed from a massive block of polystyrene, to marvel at his talent.”

The composer Simon Fisher Turner recalled Jarman’s sets as having the feel of a theater company: “He was immensely knowledgeable but didn’t wear that knowledge heavily. I knew nothing about Yves Klein (when we did Blue) or Caravaggio, but instead of looking at me stupidly, he just said: “Right, let’s go to the National Gallery.”

Jarman was restless, endlessly inventive. He began his filmmaking career with Super 8 movies, and while—as his reputation grew—so did the funds for his films, his lo-fi philosophy remained. If another director complained about not having money, Jarman would chivvy them to start filming something, anything. His agent Tony Peake told me Jarman would have been “You Tubeing like mad” had he lived. All his friends noted his zest for living, his sense of fun and outrage, his intelligence and love of gossip, his kindness and spontaneity.

Peake said Jarman was utterly radical, yet with the small “c” conservative qualities of his very English parents—his father had been a pathfinder with the Royal Air Force, and Jarman inherited his mother’s “grace under pressure” quality. “I sometimes think of Derek like his dad,” said Peake—“tenacious, showing bravery in the face of enemy fire, keeping steady and flying through it. He was a pathfinder, too, forging his own way.”

The pop star Toyah Wilcox, who starred in Jubilee and The Tempest, recalled shooting one scene with two men in bed and being very surprised to find them naked under the sheets. When she had no money, he made her mushroom soup. “Because he was always such an eloquent gentleman, it was amazing to see those angry canvases he painted about dying and prejudice before he died,” she said. “They affected me hugely: They conveyed the way people with a terminal illness must feel. The one memory I really treasure of Derek is laughter. Laughter was etched on his face all the time.”

Burston’s standout memory of Jarman was the day he was “canonized” by the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence—a group of drag nuns who combined theatricality with activism—and paraded down Old Compton Street in Soho, dressed in incredible robes.

“It’s hard to imagine now,” says Burston, “but Old Compton Street wasn’t the gay drag it’s become.” Burston met Jarman at his little office, the walls papered with huge photocopies of homophobic tabloid headlines. Jarman was sitting there, “smiling and energized,” working on his paintings and At Your Own Risk, which Burston contributed to.

“We used to go for food at a little Italian place on Old Compton Street called Presto,” says Burston. “The staff all knew him. There were photos of him on the wall next to the table where he always sat. After he died, it became more like a shrine.”

The last time Burston saw Jarman was shortly before Blue came out. There was a small private screening, and at the end of the film Burston turned around to find that Jarman was sitting a few rows behind him. “He was blind by then, and very frail. There were tears rolling down his cheeks. He was never sentimental about AIDS. He once told me that he hated AIDS films because of the sentimentality. So to see him so emotional had a profound effect on me. His funeral was very traditional. I expected it to be less traditional, more celebratory, possibly even a little camp. But Derek was a mass of contradictions.”

Simon Fisher Turner told me he last saw Jarman lying dead in the hospital chapel. “It wasn’t morbid at all. He was in these amazing robes and looked like a bishop. I thanked him and told him not to worry about himself, or us, and that I loved him. I think I cried. And I told him he looked fantastic.”