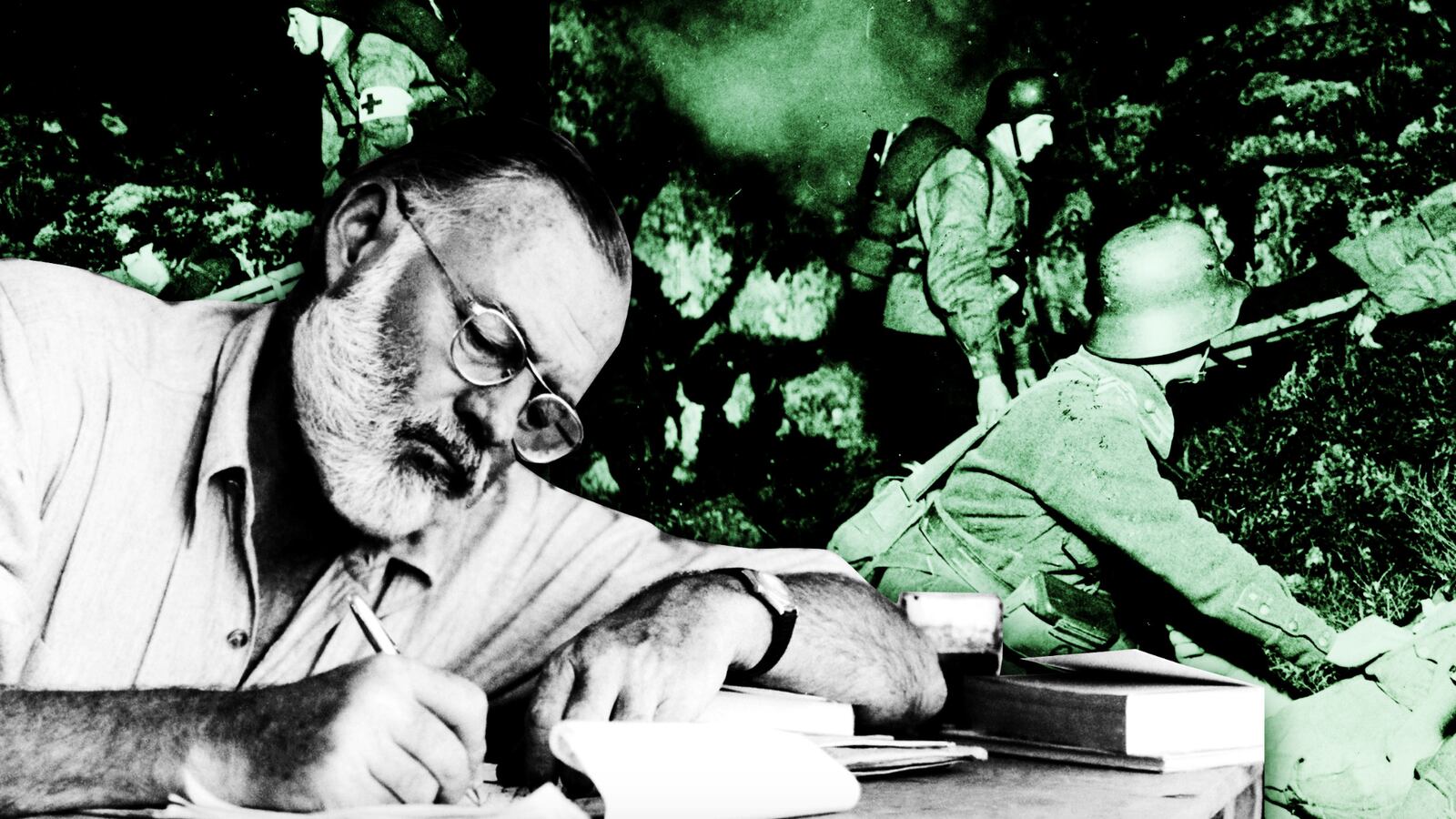

The publication of Ernest Hemingway’s 1956 short story, “A Room on the Garden Side,” in the current issue of The Strand Magazine, a literary quarterly, has generated widespread interest. Until now “A Room on the Garden Side” was available only through the Hemingway Collection at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston.

“A Room on the Garden Side” is a find for anyone interested in Hemingway, but what is surprising about the story, which is set during World War II, is how much it speaks to the present moment when America’s obligations to other nations, especially our European allies, have been thrown into question by the Trump administration.

The turning point in “A Room on the Garden Side” comes when Robert, the story’s narrator and a Hemingway stand-in who, like Hemingway, is called “Papa,” explains why he is engaged in combat that he might easily avoid. Robert’s explanation for the obligation he feels to take part in the war reflects the life he has chosen for himself, and the art of “A Room on the Garden Side” lies in the way we are gradually brought to identify with Robert.

To help readers come to terms with “A Room on the Garden Side,” The Strand has published it with a thoughtful afterword by Kirk Curnutt, a board member of the Ernest Hemingway Society.

The title of “A Room on the Garden Side” refers to the location of the room Robert has been given at the Ritz hotel just when Paris has been liberated from Nazi control. The situation parallels that of Hemingway, who arrived in Paris on August 25, 1944, with a group of irregular troops he had gathered in the small French village of Rambouillet.

At the time Hemingway was officially a correspondent for Collier’s, but in Rambouillet he went far beyond his journalistic role, casting aside the doubts he expressed about himself earlier in the year when he wrote his wife, the journalist Martha Gellhorn, “Just feel like horse, old horse, good, sound, but old.” In conjunction with Colonel David Bruce of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner of today’s CIA, Hemingway and the French irregulars with him at Rambouillet did their best to defend the village and locate the scattered German forces around it. When General Jacques LeClerc, whom the allies had given the honor of liberating Paris, arrived, they gave him the information they had gathered and then followed LeClerc’s Second Armored Division to Paris before entering the city on their own.

In his diary, OSS Against the Reich, Bruce, who later served as ambassador to France and England, records how, when he, Hemingway, and their driver entered Paris in their jeep, the Champs Elysees was free of traffic and they were able to make their way to the Travellers Club and from there to the Ritz, where Hemingway was fondly remembered from the time he spent as a young writer in Paris in the ’20s.

“A Room on the Garden Side” takes place within the confines of the Ritz. It includes much that is factual. Hemingway uses the first names of partisans who were with him and recounts an actual meeting that he had at the Ritz at this time with the French novelist Andre Malraux. But the heart of the story hinges on conversations with himself and others that Robert has about writing and warfare. We don’t get much about wartime Paris or the charms of the Ritz in “A Room on the Garden Side.”

Robert, who is relaxing by reading Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal, speaks about such French writers as Marcel Proust and Victor Hugo and in doing so, he is forced to acknowledge that, although a writer, he is now using his time to fight rather than write. By way of justifying himself, Robert, who admits that he enjoys combat, observes, “I did it to save the lives of people who had not hired out to fight. There was that and the fact that I had learned to know and love an infantry division and wished to serve it in any useful way I could.”

The justification is brief in terms of the space it takes up in "A Room on the Garden Side" and departs from Hemingway’s own history, making no mention of the difficulty he got into as a result of what he did in Rambouillet. It is against the protocols of the Geneva Convention for war correspondents to take part in fighting, and rival correspondents, resentful of Hemingway’s actions in Rambouillet, reported him to the military.

In early October 1944, Hemingway was ordered to report for a hearing at the headquarters of the inspector general of the Third Army, but the last thing the Army wanted to do was punish America’s leading novelist and send him home. Hemingway was acquitted of all the charges against him at a hearing at which, he later acknowledged, he was coached ahead of time on how to give answers that would keep him out of trouble.

The impact of the hearing on Hemingway was to make him even more confident that he was right to take up arms when he did. It was not, he believed, enough to bear witness to history. It was necessary to act.

Twelve years later, when Hemingway fictionalized the events of 1944, his convictions had not changed, but the bitterness that had prompted him to write a friend in the wake of his hearing, “Beat rap,” was gone. Robert has no hesitation about returning to battle, and nothing in “A Room on the Garden Side” suggests that Hemingway worried that in the future an American president might turn his back on the moral values Robert espouses.

In a 1956 letter to his publisher, Charles Scribner Jr., Hemingway, who two years earlier received the Nobel Prize for Literature, was confident enough about “A Room on the Garden Side” and four other short stories that he wrote at this time to assure Scribner, “Anyway you can always publish them after I’m dead.”