Imagine this: You’re a single mom who gets pregnant in Louisiana, where the state banned abortion the instant the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v Wade. Every surrounding state—Texas, Oklahoma, Arizona, Mississippi—has banned abortion, too. If you are like most people in Louisiana, your closest clinic will be at least a 10-hour drive away, in Illinois. You will need to pay for fuel, lodging, and of course, your abortion, which insurance will not cover. You will have to take time off work. You will have to secure childcare. If you are like the majority of people seeking abortions in Louisiana, you are already living under the poverty line.

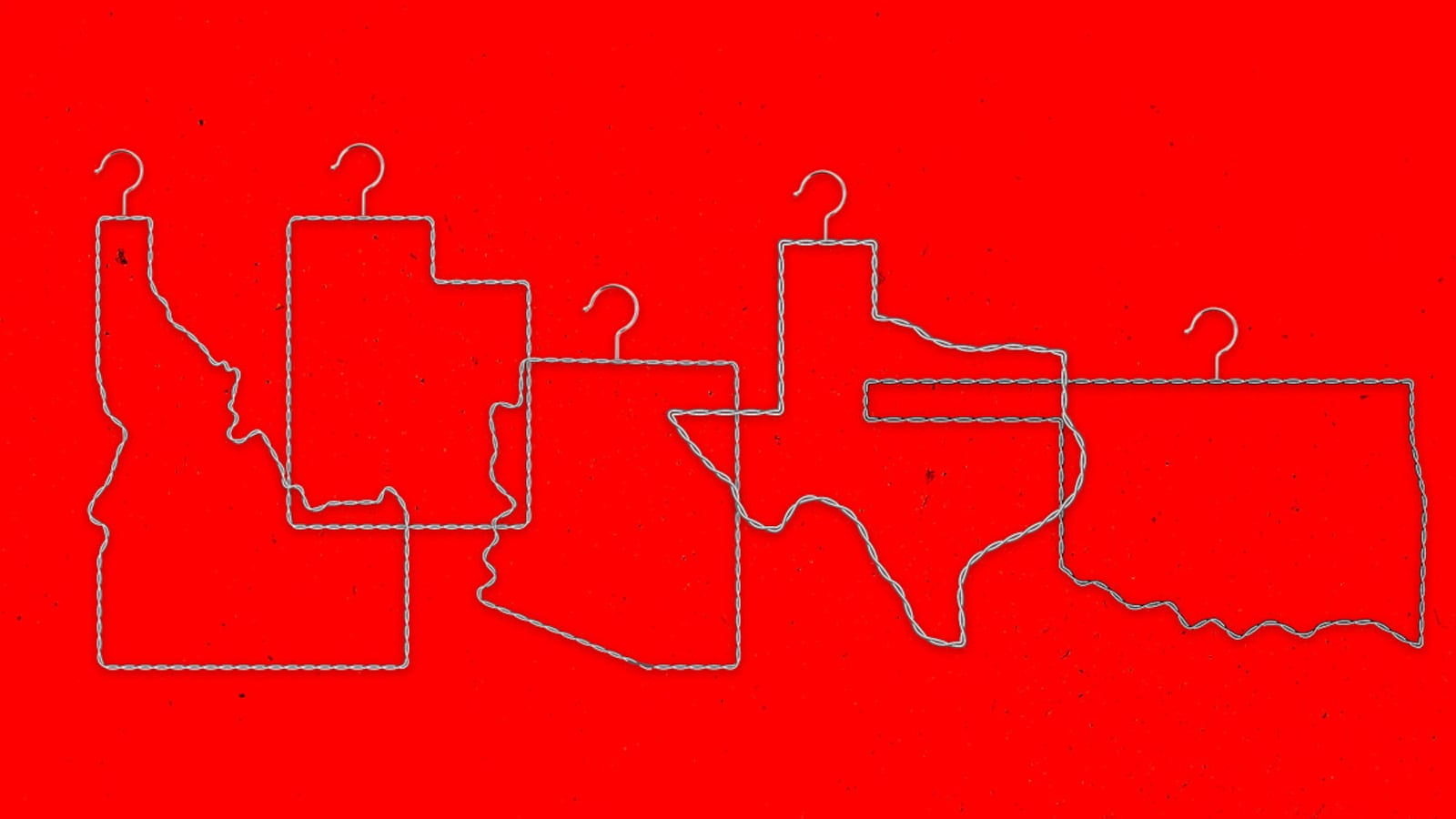

This is the reality of what abortion access will look like for thousands of people in Louisiana if the Supreme Court follows through on its draft decision to overturn Roe v Wade. According to data compiled by the Guttmacher Institute, 18 states have laws on the books that would immediately outlaw abortion if Roe were overturned, and four more have six-week bans slated to take effect. Four others have indicated a desire to ban abortion entirely.

In effect, this means less than half of all states will maintain the legal right to abortion if Roe falls. And residents of Louisiana, according to Guttmacher, will be hardest hit of all.

“The women we see, they don’t have the means to hop a flight to wherever,” said Kathaleen Pittman, clinic administrator at Shreveport-based Hope Medical Group For Women. “The majority of them won't be able to travel, they won't be able to make that trip. They will be forced to continue the pregnancy.”

Approximately 10,000 women obtain abortions in Louisiana each year. The state already bans abortion after 20 weeks, telemedicine for medication abortions, and public funding for abortion except in cases of life or death. It also requires abortion providers to register as ambulatory surgical centers—an onerous requirement that research shows does not improve outcomes. The state previously attempted to require abortion providers to secure admitting privileges at local hospitals—a restriction that would have shut down every clinic in the state—until the Supreme Court shot that down last year.

In part because of this, the number of abortion providers in Louisana has dropped steadily, from five in 2014 to the current three. (Maternal mortality in the state, meanwhile, increased 28 percent between 2016 and 2018.) It is a trend seen across the country: The number of abortion clinics nationwide has steadily declined since at least 2010. As of 2014, according to a study by Guttmacher, one in five women had to travel more than 40 miles to reach their nearest abortion provider. For women in rural South Dakota, the trip was more than 300 miles. If Roe falls, abortion-seekers in Louisiana will be an average of 666 miles from their nearest clinic—the farthest in the country.

The combination of clinic closures and new state restrictions is already straining the remaining providers. Pittman said her clinic has a waiting list 300 people long—largely because of an influx of patients fleeing Texas’s recent six-week ban. The wait times are pushing patients further and further into their pregnancies, making the procedure more complex and more expensive than it otherwise would be. The number of second-trimester abortions the clinic performed in the first three months of this year was double that of the year before, Pittman said. “And that’s because of the delays,” she added, “so you can imagine how additional delays are going to affect these people.”

If Louisiana outlaws abortion, the situation will only get worse. All of the surrounding states either have trigger laws or pre-Roe bans on the books, so patients would likely be pushed into Illinois, Kansas, and North Carolina. In Kansas, patients are already required to receive counseling intended to discourage them from getting an abortion and wait 24 hours before the procedure. In North Carolina, the wait time is 72 hours—meaning that even in the best circumstances, getting an abortion would require being away from home for at least three days.

More than 70 percent of abortion patients in Lousiana in 2015 were women of color, according to the Center for Reproductive Rights, and the vast majority were poor. (Louisiana overall has the third-highest poverty rate in the country.) Public insurance plans like Medicaid cannot over abortions except in cases of life endangerment, rape or incest; nor can plans offered on the state’s Affordable Care Act exchange. Even private insurance plans require participants to purchase a special rider if they want coverage for abortion.

Combine that with the costs of fuel, lodging, child care and days off work required to travel out of states, and not only would abortion be physically out of reach for many people in Louisiana, it would also be unaffordable.

Michelle Erenberg, the executive director of abortion advocacy group Lift LA, said she heard from a patient just this week who was 16 weeks along and wanted an abortion. Louisiana bans abortions after 20 weeks of pregnancy, but because of the clinic delays, Erenberg said, the woman was not going to be seen in time. Erenberg connected her with a local abortion fund that could help her afford the trip to nearby New Mexico, which has no such restriction.

Erenberg was optimistic that the abortion fund was able to help the woman. But if Roe falls, she doesn’t know how long that would last.

“It’s one thing to do that for a couple hundred people in one state,” she said. “But when you’re looking at half the country and millions and millions of people ... it’s pretty terrifying.”

In light of the draft Supreme Court decision, Erenberg said, activists need to focus on buttressing support networks like these. She also emphasized the need for increased access to contraceptives, and for legislation decriminalizing self-managed abortions. “We cannot be living in a world where people are going to jail or not going to the hospital if they have a pregnancy complication because they're fearful of being arrested,” she said.

Pittman, meanwhile, said she was too busy getting through her clinic’s backlog of patients to figure out what came next.

“I’m concentrating on these women, because they're the ones who need me,” she said.

“I really wish I could be more insightful,” she added. “But right now I’m tired and I’m angry.”