Damian Lillard, the Portland Trail Blazers’ star point guard who will be squaring off with Steph Curry and the Golden State Warriors in Game 1 of the NBA’s Western Conference Finals tonight, is just a tremendously sincere young man. I understand that when you read a sportswriter saying that a player really means it you don’t believe them—you presume they’re carrying water—but I’m dead serious here, Dame just really means it.

Take, for instance, his choice of number zero, or “THE LETTER O,” as the Blazers PA announcer will tell you. It’s a triple-stacked tribute to his hometown of Oakland, to Ogden, Utah, the home of Weber State University, where he went to college, and to Oregon, where he was drafted, has played for the last seven years, and captured the hearts of a fanbase that has been looking for an unambiguous champion for its entire existence. Lillard is widely regarded as a supreme teammate, and has said that he would never seek a trade because he wouldn’t want to put his teammates and coaches in hot water.

There are times when I, a Portland fan, feel weird rooting for him because my personal taste in players runs cynical. Most days, please, give me a Rasheed Wallace, treating refs like dogs; Draymond Green, doing everything he can to wack his opponents in the testicles; James Harden, driving the world into frothing madness with his endlessly deep bag of foul-drawing tricks. But the years and the success and the startling clutch shots and Dame’s perpetual good vibes have converted me: I’m terribly fond of our Sincere Basketball Man, to the point where I think he should never be traded under any circumstance.

But there is a strange element to having an open-hearted young man as your basketball hero. Open-hearted young men often express themselves through art, and Damian Lillard is prone to the art of rap.

When the 28-year-old steps behind the mic, he transforms into Dame D.O.L.L.A., a rapper who pretty much raps about the life and feelings and values of Damian Lillard. Considering the embarrassing history of NBA rappers, Dame is surprisingly skilled. His flow is decent—he’s not exactly seeking high-end melodic or rhythmic ecstasy so much as he is talking about his life, his family, women he’s hitting on, stuff like that.

Honestly, it’s a little strange listening to a guy that rich sit back and examine his life as a banality, as opposed to an orgy of excess. Lillard’s whole thing when talking to reporters or fans or whoever is humble origins, being community and family-focused, all that kind of stuff, and his on-record rap career is an extension of that. Take, for instance, this verse from “Loyal To the Soil,” off of Dame’s 2016 debut album, The Letter O:

I come through with no security

I grew up in the slums ain’t no fear in me

Now the lames come and go and no forgetting me

They in love with the life and I don’t know Billie Jean.

Look at my demeanor, see loyalty in my background

Love me cause I’m solid, not because I became a cash cow

Tryna make jobs for younglings, that’s on the ave now

That’s why I can’t have a barbecue and don’t have a pat down.

Celebrating a place, people, giving your time, trying to keep one’s self humble, or some approximation of it—it’s the Lillard ethic on wax, the same message he says to every reporter he talks to spread out over a lengthy rap verse. So much of his work is about trying to not become a lunatic or make everyone around you a lunatic when you become rich. The anxiety comes from the worry that he might lose touch.

While I wouldn’t say Lillard is slinging metaphors at some Biggie level, Dame manages to string together phrases that are comprehensible and thematically consistent. He doesn’t curse, because, like Wu-Tang before him, Dame D.O.L.L.A. is for the children, and Dame doesn’t “want to have that type of impact on kids.”

In “Trap Party,” probably his strangest song, he talks about attending his friend’s funeral in Oakland, feeling judged by the other people there (“Because I’m closer to Kobe”), buying out the bar to try and make it a good time, and talking to his old friends about good times’ past. The dissonance between his life and the lives of the people he grew up with, and the feelings that come from that, are expressive and strange, a look into an experience I don’t think would have even occurred to me before I sat there and listened to him spell it out.

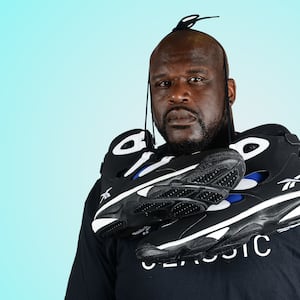

When NBA players find themselves executing this gambit, it always reveals something about them. When Shaq dropped his platinum-selling 1996 rap album Shaq Diesel, he mostly did big-boy beefy-mean battle raps, rasping over aggro, better-than-they-had-any-right-to-be beats about how easily and completely he could dominate you. This tracks with Shaq, who is, of course, a gigantic beloved bully who thoroughly dominated and embarrassed anyone who ever guarded him and spent his career busting balls in the locker room. Allen Iverson, operating under the pseudonym “Jewelz,” made an unreleased gangster rap album the NBA openly objected to because he freaked them out. Kobe Bryant made a regrettable song with Tyra Banks called “K.O.B.E” because he is the primary object and subject of his own life.

With Lillard, it’s different: a super-sincere guy making super-sincere rap songs about his feelings and his minor struggles that your kids can listen to; thoughtful music about trying to be a good dude, sentiments that are pretty much in line with how I’ve experienced him as a basketball player and a member of my favorite team. Hopefully he will crush noted Pizzagater Andrew Bogut and the rotten, loathsome Warriors, but even if he doesn’t, it’ll be fine. He’s still good by me.