Techno-trance raves have been part of the Israeli music scene for years, drawing thousands of young people from around the world to dance in secret locations revealed just hours before the event. These underground festivals are often timed to celebrate Jewish holidays and occur in open fields or deserts.

The Supernova (Nova) Music Festival, one of the largest underground electronic dance music (EDM) parties in Israel’s history, drew 3,000 to 4,000 fans to an open-air space in the Negev Desert in Southern Israel, some three miles from the Gaza border, near Kibbutz Re’im. The event featured 16 DJs from around the world and was timed to mark the end of Sukkot, a weeklong Jewish harvest holiday that also celebrates the historic freedom of the Israelites from slavery in ancient Egypt.

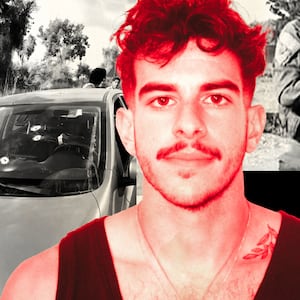

In the early hours of Oct. 7, Hamas terrorists descended upon the Nova Festival, turning an overnight rave into the worst slaughter of civilians in Israel’s history. Upwards of 260 revelers were brutally killed, and an unknown number of others were kidnapped.

A group of mental health workers in Israel rallied to provide emergency relief to its young survivors. Below are interviews with three members of Nova Help.

Yair Grynbaum, paramedic and founder of Nova Help: On the morning of Oct. 7, I was in Egypt, where I was traveling with my wife and friends.

I’m a paramedic trained in search and rescue and crisis management. I knew I wanted to help and we all wanted to return home. We immediately booked taxis to get us to the border and then within four hours, I was back at my home near Haifa. Then I began contacting colleagues.

My first call was to a peer in the Safe Shore Project, a group that offers psychedelic harm reduction at raves in Israel and Europe. Many festival goers take psychedelic drugs and need support, which is how we began our group. We heard that our partner organization, Anashim Tovim, which literally means “good people,” were on site at Nova, so I called them and heard back.

They told us that the biggest rave in Israel since COVID became the bloodiest massacre. We knew we were in uncharted waters and would require a new level of treatment. I contacted Dr. Reut Plonsker, who also wanted to aid Nova survivors.

Reut Plonsker, clinical psychologist: Yair and I are good friends and met through our work at raves. As a veteran of Israel’s Burning Man and part of the party scene, I saw there was a need for safe spaces for people having difficulty at these festivals, often because of psychedelic drugs. So in between my in-clinic work, I offer harm reduction at festivals.

I didn’t know about Nova because it attracted a younger age group than mine. But the scene is small in Israel. We’re all family. This is my tribe. I quickly heard from friends who had younger siblings there, some of whom had fled to the nearby kibbutz Re’im, which already had been ambushed by Hamas.

I learned a friend of mine who lives there was kidnapped with her two small children (3 and 9 years old), her husband, and parents. She’s a clinical psychologist like me. We studied together. That really hit home. I’m also a mother with a 1-year-old baby. That she was taken with those small kids killed me. I knew I wanted to help.

Israeli soldiers inspect the burnt cars of festival-goers at the site of an attack on the Nova Festival.

Amir Cohen/ReutersI asked Yair, what can we do? So many people will come out of this with major trauma and will need help. So we built the website Nova Help, that anyone who was at Nova can access. All they have to do is either fill out the form or call the number. It’s not like usual mental health platforms, where I wait for the patient to call me. After they input their details, we call them.

Yair Grynbaum: From day one we recognized these traumas are new and that this is an unprecedented mental health crisis.

So we knew we had to act fast and come up with a whole new treatment protocol with cutting-edge therapy and a diverse group of specialists from social workers to clinical psychologists trained in supporting survivors of sexual assault to neuropsychologists, drug dependency specialists, grief counselors, those more trained to address crises and acute situations, so we try to find the best match for each patient.

At our core, we are a community of non-judgmental therapists who are used to alternative spaces and are very compassionate. We get hundreds of calls a day and unlike most mental health services, which respond within 24-48 hours, we respond right away. We know this is an emergency and every minute counts. We also offer three free therapy sessions for each person who reaches out. We were up and running by Sunday 8 a.m..

Dr. Mor Forbin, clinical psychiatrist: The morning of Oct. 7,, I got a call to report to my [IDF] reserve unit. But my duty was short lived. Sunday morning, while running to the bomb shelter, I badly injured my leg and was sent home to recuperate.

I had cleared my schedule of patients because of my reserve duty, but wanted to help. As I was contacting the health support group on my kibbutz, I heard from Yair.

I’m a psychiatrist who specializes in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), including training in Hakomi (a form of mindfulness-centered, somatic psychotherapy), and I recently got certified in EMDR, which stands for Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing. (It’s a type of therapy that involves having a patient focus on a traumatic memory while stimulating a bilateral response in their body, typically using a device to get their eyes moving from one side to the other.) I also studied at the Center for Psychedelic Therapies and Research at the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco. It’s as if all my training prepared me for this moment.

Within an hour, a young man knocked on my door and needed immediate support. His family lived in Kibbutz Kfar Azza near the Gaza Strip, the scene of one of the most horrific scenes of carnage with babies burned in their cribs. This young man hadn’t heard from his parents or relatives. They are still missing. When he showed up that day, he looked terrified. He had attended the Nova music festival, too, and was reeling from a harrowing escape and hadn’t slept.

One of my first patients that Sunday, Oct. 8, told me he survived by lying under his friends’ corpses, blood dripping all over him, as he tried not to move while they were shouting, shooting, and surrounding them looking for more people to kill—for three hours. The human mind can’t comprehend that level of evil. I’ve treated 15 survivors of Nova so far, and each of their stories reminds me of stories my Holocaust-survivor grandmother shared with me.

Israeli soldiers walk through the site of an attack on the Nova Festival.

Ronen Zvulun/ReutersOften, survival is predicated on luck. One of my patients said after hours of hiding, he got so hungry and thirsty he thought he was going to pass out. He saw an orange sitting just beyond his grasp and almost stood up to grab it. By some miracle he didn’t act on his impulse. Within seconds, terrorists entered the space and began firing. He would have been killed instantly had he risen up.

Another survivor ran for cover in a small room where people were stacked like dominos. Suddenly a terrorist burst in and asked for their phones. He was sure they’d all be killed, but suddenly, he ran off.

It reminded me of my grandmother Henya’s story of fleeing into the Lithuanian woods with her baby, my aunt. Nazis found her and grabbed her baby, throwing her from one to the other, laughing, as they got their guns ready (Nazis would toss and shoot Jewish babies as if they were clay pigeons). For some reason, the Nazis suddenly ceased and ran off. My aunt survived and is an 83 year-old retired doctor.

Yair Grynbaum: We treated over 1,000 cases in five days. We have since grown to 400 therapists, meeting the needs of 1,500 Nova survivors so far. We also ensure our therapists get individual counseling since secondary trauma is a real thing. And we also have an online group chat where we can unburden and feel safe and supported among peers.

We have more than 15 clinical guidance therapists, and 20-30 more who just counsel our therapists. Each therapist should have treatment anyway, but especially in this case. They work from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. or longer, rotating between in-clinic and Zoom, whichever the person requests. I manage the caseload and try to find the best match for each caller, and work with a team of others who are trained in crisis management.

In terms of the trauma, imagine being at a giant dance party, celebrating life with loved ones in nature, dancing to music and celebrating being alive, and then all of a sudden, you’re running for your life, watching your friends being killed, raped, tortured, while the terrorists are cheering these horrific murders.

The soul is torn apart, particularly if the person was on psychedelic drugs. The soul is jumping from one end of the spectrum to the other; the situation is surreal, the body shuts down and the mind has a problem processing it. Who can comprehend this, after not sleeping and being high dancing all night?

Dr. Mor Forbin: Normally, when you’re in a dangerous situation, your body is programmed to do four things: fight, flight, freeze, or beg for your life. Your brain, which normally processes information, shuts down.

All you’re left with is a shattered memory, a picture that you can’t quite piece together, that lives in the shadows and prevents you from functioning as you did. It may stay as a signal or warning, blocking you, making you afraid to go near a location that reminds you of where the trauma occurred. You live in a heightened sense of danger, your body is full of fight and flight hormones and you don’t feel safe. So the first thing we try to do is to ground them and make them feel safe.

Reut Plonsker: In the first session, we try to give tools to help them expel the trauma in a physical way. We advise them to jump, walk, and let the body release some of the stress and tension from inside. We also work on relaxation, breathing and easing anxiety, while helping them feel in control of their lives again.

One of the keys is to help them see the event as having occurred in the past. In this time of acute stress disorder (ASD), the mind is still in a battle. We reassure them that they’re not being chased by terrorists, and that it’s not the same as it was on Saturday, that the worst is over and that they’re safe at home. We realize they’re still living in fear, sometimes they don’t tell the whole story because it’s re-traumatizing, so we assess whether they’re ready.

Dr. Mor Forbin: In the second session, we work on helping them form a narrative that they can live with.

What I mean is because their lives have been shattered, and that image of the event exists like a snapshot they can’t quite understand, we tell them to share their story of survival.

Traumatic memory leaves survivors with a fractured sense of the events. They remember the feeling of being under attack, but they can’t necessarily recall each detail. That’s how the mind protects them. Shaping a personal narrative helps them put the pieces together so the trauma of that event doesn’t control them. And it also helps them access feelings that are hard to accept.

Survivors of any catastrophe are racked with guilt. They ask, why me? I didn’t deserve to live and not my friend. I’m not such a good person.

That’s why intervening in the immediate aftermath of such an event can prevent someone from developing PTSD, even though 90 percent of survivors heal on their own.

Trauma takes us to the edge. Our brains are overwhelmed and make us remember the worst of the worst. But it’s important to help them see that they made the right choices in these unbearable situations and all that helped them survive.

An aerial view shows abandoned cars of festival-goers at the site of an attack on the Nova Festival.

Ilan Rosenberg/ReutersReut Plonsker: Sometimes, we hear of a survivor who found a weapon and was able to kill a terrorist or fight them off.

I try to help them see their active role in their story, that they had control and they helped themselves and others. They all feel survivors’ guilt, everybody in Israel does, including me. We all feel, “I could have saved another person.” So we try to highlight how they saved lives.

They all lost so many friends, seven to 10 on average, they have to choose which funerals to go to now. This also makes them feel guilty, in addition to the fact that they escaped and are alive when their friends are dead. Some can’t cry at the funeral because they’re still in shock and they feel everything in their lives is unstable. Because they feel their survival hinged on a split-second decision, they don’t trust that their lives will ever be stable again.

One of the major aspects of PTSD is that your life is at risk and governed by uncertainty. They hear gunshots and experience hallucinations, so I try to normalize these symptoms. I tell them it’s OK to have these sensations in this phase, and that it’s not a sign they have PTSD, which often can’t be diagnosed until six weeks later. The better they are at shaping their story, the better their outcomes.

One survivor told me he used humor to survive. He made himself joke about the events occurring around him because they were too horrible for him to take in on face value. How wonderful is that?

Humor is a safeguard, the very mechanism that protects us from anguish and plunging further into sorrow, it’s a defense of the soul. He thought there was something wrong with him, but I assured him, his ability to talk himself through the crisis, while trying to find humor made him exceptional.

By the third meeting after we build a narrative, we get survivors to balance the more complex emotions, which range from guilt to fear, from uncertainty to grief, to the joy of being alive. These are young people who have had to process unimaginable terror, violence and sorrow, and to navigate all the emotions together, is a heavy burden. They feel so bad, so I assure them that their ability to even discern the complexity of their situation is very healthy.

How do I feel? I am furious about Hamas, and furious about the government, but now we have to stand together. I, too, have to balance all these sometimes-conflicting emotions together.

Fortunately, I don’t see a lot of anger in the survivors I’m helping. They’re more scared and overcome with fear and grief than anything.

A father helps bury a victim of the Hamas attack at the Nova music festival.

Leon Neal/Getty ImagesDr. Mor Forbin: When someone is still feeling very guilty, I try to turn the negative into a positive and reassure them that the fact that he’s feeling guilty proves that he has a good heart, is full of kindness and humanity.

If someone is having a hard time sleeping or is in too much shock to cry, I might try something like EMDR. I ask survivors to recall a traumatic event while I move my fingers rapidly from side to side. As they tell their story while tracking my hand movements with their eyes, their brain can reprocess the memory so it’s whole, not fragmented as it had been, which helps them heal.

Compassion is the key. I tell them it’s OK not to cry and to feel what they’re feeling. Sometimes just validating their emotions helps them access them.

One young man was finally able to cry after I told him that he needed to be kinder to himself and to be patient and allow his body and mind to heal. I often cry, too. How can you not when you hear a story of someone lying under the corpses of his dead friends for hours? I’m glad I can access my feelings. That’s what it means to be human. And I’m glad I can help others.

At the end of a day, I feel fulfilled that I can honor my duty as a doctor and an Israeli citizen. For the first time in my career, almost every patient hugs me at the end of the session, which is unorthodox. I can’t describe how fulfilling that hug is. I’ve never hugged my patients before. You’re told not to. But this feels right. They feel grateful I helped, and I’m grateful I can help. We are one big family here in Israel.

And we will overcome this, the way we overcame the Shoah and all kinds of other tragedies that this Hamas massacre reawakened in our collective Jewish psyche.

Grynbaum: Nova Help has grown to nearly 400 therapists. We’ve treated 1,500 survivors of the Nova Festival massacre. We are an all-volunteer organization. But we hope to continue for a year and add more services for those who need more than three sessions.

Reut Plonsker: I work very hard, but I feel I have a purpose in this crisis. Because I have a baby, I have to smile, so I can’t walk out of the sessions crying all the time. I am able to sleep, though sometimes it’s very hard to fall asleep. I lay awake for hours, though I’m very tired and very sad. Every three days I cry for two hours. I think of my friend who was kidnapped with her whole family or I’ll hear from parents who lost a child, and I tell myself how much worse they have it.

Nova Help is a life saver for so many, but also for me. Helping others helps me.

For more info on Nova Help, go to https://www.novasupport.org.