On the morning of May 30, 1893, a circus train convoy chock full of lions, elephants, and camels fatefully rounded a bend of a rural Pennsylvania mountain.

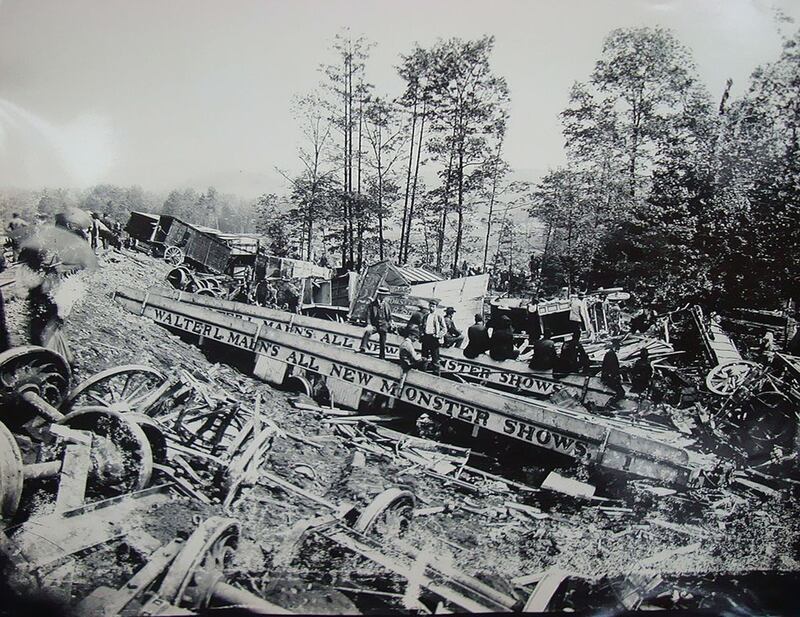

The conductor was going 40 miles an hour, and the Walter L. Main circus flew off its rails.

Fourteen of its 17 cars tumbled down a 30-foot ravine, piling on top of each other. Hundreds of animals streamed out and into the surrounding forest.

The circus had come to town unexpectedly in Tyrone, Pennsylvania.

Luckily, the performer car had stuck to its track. But even so, five circus employees were killed along with dozens of animals.

Two so-called “sacred” cows and 50 horses died in the wreck, and countless animals were injured. Those who weren’t seized their chance at freedom.

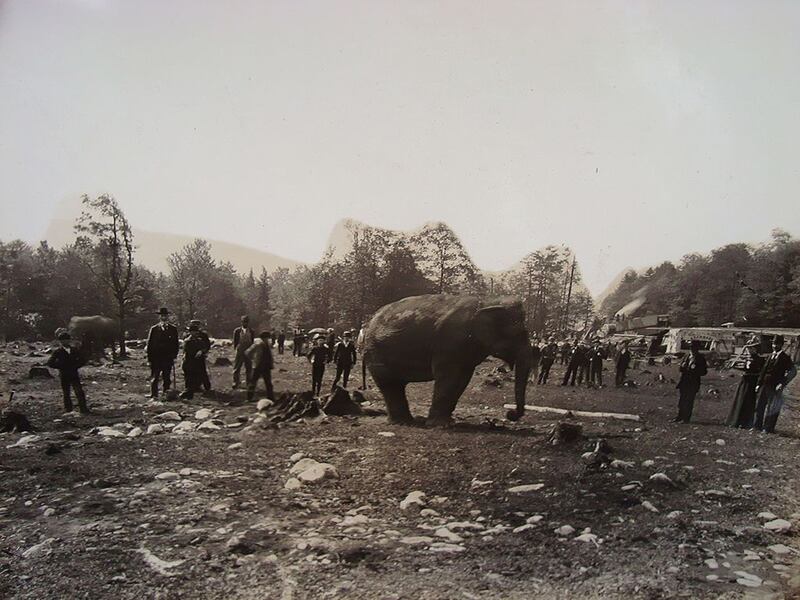

A gorilla, tigers, lions, zebras, alligators and other exotic beasts took the opportunity to slip their broken chains and cages to make a run for the nearby woods. The elephants, camels and others were retrieved, but many were not.

An unfortunate fate befell the Bengal tiger, who quickly began hunting the local’s cows.

A bear hunter was summoned to take care of the problem, and the tiger’s skull is on display today in the town’s hunting club.

The local hospital took in the human injured, and a newspaper item the next day listed those receiving care. The first poor soul, John Chambers, had reportedly been “bitten severely by a lion.”

The circus, which was on its way from Lewiston to Honesdale, spent more than a week at its unplanned stop. Then it got back on the road, traveling through Pennsylvania, New York, and Massachusetts for the rest of the year.

Main’s circus opened its first show in 1879, founded by an 18-year-old farmer’s son who found himself unsuccessful in his father’s field. It took the better part of a decade for Main to hit it big, but by 1891 he had become popular enough to add an elephant, a big top, and 11 railroad cars.

The derailment two years later was devastating, but Main recovered and continued his roadshow for a decade. An advertisement published in New York two months later bills it as the “grandest and best” show on earth. He sold it in 1904, but in name, the Walter L. Main circus persisted until the late 1930s.

Long after the circus’ departure, the century-old tragedy has haunted Tyrone.

Between 1895 and 1958, the town of Tyrone honored its dead with a memorial service for victims both human and animal.

Often, circus performers would return to pay tribute.

The escaped animals persisted in local lore. For years, townsfolk would report kangaroo, parrot, and snake sightings, presumed to be the descendants of those freed performers.

The one big mystery that remains from that spring day is the final resting place of the victims. The horses and cows had been hastily buried in a mass grave on a local farm, along with bits and pieces of the wreckage that couldn’t be salvaged.

The family living there now has been unearthing these scraps for years: bones, horseshoes, and other relics from the site, according to Live Science.

Last year, locals and historical sleuths decided to finally identify the final resting place of the crash’s animal victims.

A team of grad students from Indiana University of Pennsylvania did a radar scan of the crash site. The survey covered three acres of land, but was inconclusive and bad weather made a full excavation impossible.

Even without a grave location, the town has continued to pay tribute to its unfortunate, unexpected guests.

Susie O’Brien, on whose land the burial site is under, reinstated the traditional yearly memorial in 2009 when she enlisted two elephants passing through with a nearby circus to aid in the ceremony.

This past May, the town celebrated the wreck’s 122nd anniversary. “Again this year we will have clowns at our memorial,” a news posting assured readers.