It began with an Esquire magazine interview in which Terry Southern sat down to talk with Stanley Kubrick. Back in 1962, Southern was famous for having written the nymphet best-seller Candy and Kubrick had just brought Vladimir Nabokov’s nymphet classic Lolita to the screen. During their interview, the two men went from discussing young female sex objects to making a high-budget pornographic film starring famous actors. Southern would eventually use that porn idea as a plot for his next novel, Blue Movie, published in 1970. But more immediate, the two men developed an on-again, off-again working relationship that included their cowriting the Dr. Strangelove screenplay and their not working on a couple of projects dear to Southern’s heart.

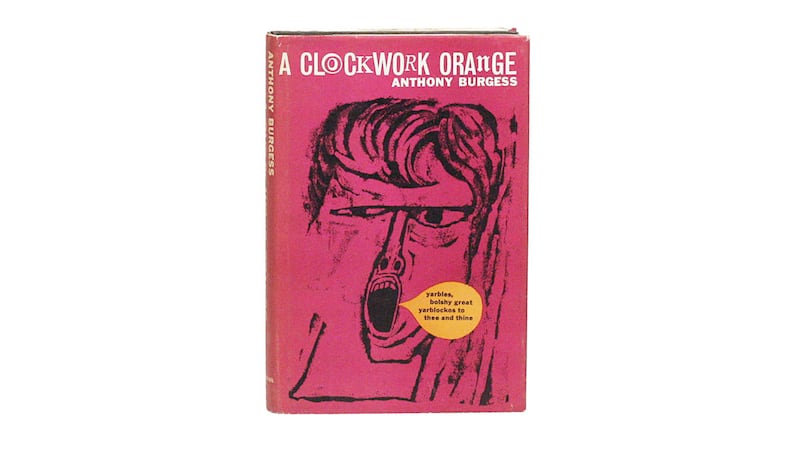

Southern had optioned Anthony Burgess’ novel A Clockwork Orange about a gang of young “droogs” who terrorize a dystopian London. He’d even written a screenplay, which Kubrick read but wasn’t interesting in filming.

“Nobody can understand that language,” Kubrick told Southern, referring to the Russian-derived “nadsat” lingo that Burgess created for his violent antihero Alex, who says things like “groodies” and “devotchkas” when, for example, he means “breasts” and “pretty girls.” There was also the little problem of the British film censors, who dismissed Southern’s adaptation—or anybody’s adaptation, for that matter—with the following condemnation of the Burgess novel, published in 1962: “There’s no point in reading this script because it involves youthful defiance of authority and we’re not doing that.”

Malcolm McDowell in Stanley Kubrick's 1971 film, A Clockwork Orange

AlamyThen there was Southern’s work-in-progress novel Blue Movie. Kubrick was more predisposed to it—or at least he liked one chapter, which prompted him to write back to Southern, calling it “the definitive blowjob.”

In the end, Kubrick was no more interested in turning Blue Movie into a movie than he was in filming Southern’s screenplay of A Clockwork Orange. Blue Movie the novel tanked with the critics and the public, even though its first paragraph coined one of Hollywood’s most oft-repeated questions, “Listen, who do I have to fuck to get off this picture?!?”

Even worse for Southern, Kubrick took a second look at Burgess’ novel about the “droogs” and deemed it his next project, after 2001: A Space Odyssey. Southern’s option on the book had lapsed, and to add insult to that oversight, Kubrick was now writing his own adaptation of A Clockwork Orange.

Burgess took the news of Kubrick’s interest in his novel with somewhat less pique than Southern. Then again, he wasn’t exactly overjoyed, either. He remarked, “I did not much care: there would be no money in it for me, since the production company that had originally bought the rights for a few hundred dollars [$500] did not consider that I had a claim to part of their profit when they sold those rights to Warner Brothers.”

A Clockwork Orange, 1971

AlamyBurgess did care, however, how Kubrick might translate his novel to the screen. He harbored ambivalent feelings about the novel. It wasn’t his favorite. In fact, “It was the most painful thing I’ve ever written, that damn book,” said the author. He wrote it to exorcise the memory of what happened to his first wife, raped by four American deserters in London during World War II. She was pregnant and lost the child as a result of the attack. A Clockwork Orange, by necessity, had to be a very graphic book. “It was the only way I could cope with the violence,” said Burgess. “I can’t stand violence. I loathe it. And one feels so responsible putting an act of violence down on paper. If one can put an act of violence down on paper, you’ve created the act. You might as well have done it. I detest that book now.”

Regarding a proposed film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, Burgess had been here before, and not only with Southern but the Rolling Stones, who briefly toyed with playing the “droogs” under the direction of Nicolas Roeg. Ken Russell was also going to direct a version but started work instead on adapting Aldous Huxley’s The Devils of Loudun to the screen.

Kubrick, suddenly inspired, finished his A Clockwork Orange screenplay in a span of a few weeks, and while there was a flurry of telegrams to Burgess to discuss the project, the filmmaker didn’t much like collaborating anyway. He saw no reason to meet the novelist. As Kubrick put it, “Whatever Burgess had to say about the story was said in the book.”

Despite his “detest” remark, Burgess had also written his own Clockwork screenplay, which Kubrick read and rejected, just as he had read and rejected Southern’s adaptation without so much as a phone call to his Dr. Strangelove collaborator. He had an assistant send a rejection letter to Southern. It read in full: “Mr. Kubrick has decided to try his own hand.”

Production began in autumn 1970, and looking back on it, Burgess wrote in his memoir, “I feared, justly as it turned out, that there would be frontal nudity and overt rape.”

And much more. Kubrick considerably sexed up the source material, although his eroticization had less to do with dialogue than visuals. For example, the Korova Milk Bar, barely described in the novel, got the full Kubrick treatment: The director had admired the nude sculptures of Michel Climent, but when the artist demanded to be paid for his work, the parsimonious Kubrick hired another designer (Liz Moore, who had created the Star Child for 2001: A Space Odyssey) to make tables and drinking fountains from naked female mannequins, complete with fluorescent wigs and matching pubic hair. Elsewhere in the film, girls in a record shop suck on penis lollipops. And one victim, the Cat Lady, received a major makeover, as did her abode, the walls replete with erotic art. In a production memo, Kubrick detailed many of his original touches, including the Cat Lady’s death by dildo when she is bludgeoned by a huge phallic work of art.

During production, the movie’s Alex, Malcolm McDowell, inquired if Kubrick had ever met with Burgess to discuss the project.

“Oh, good God, no!” exclaimed Kubrick. “Why would I want to do that?”

Or, as McDowell surmised, “Kubrick didn’t want interference from the author, who probably didn’t know the first thing about making a movie.”

McDowell turned out to be the perfect Alex. He conveyed the requisite antic anarchy, and had no qualms about appearing naked on camera either alone or with an equally naked actress—a fact Kubrick well knew from viewing McDowell’s first major stint in front of the camera, Lindsay Anderson’s movie about a revolution in an English boarding school. In If…, McDowell and actress Christine Noonan got so carried away filming their nude tussle that an assistant director quit the production in a fit of moral outrage.

Burgess was equally squeamish. Despite having much admired Paths of Glory and Dr. Strangelove, the novelist was not a fan of Kubrick’s Lolita, and he feared what would happen to A Clockwork Orange when all the sex and violence had to be visualized onscreen. “Lolita could not work well,” Burgess wrote, “because Kubrick had found no cinematic equivalent to Nabokov’s literary extravagance. Nabokov’s script, I knew, had been rejected; all the scripts for A Clockwork Orange, above all my own, had been rejected too, and I feared that the cutting to the narrative bone which harmed the filmed Lolita would turn the filmed A Clockwork Orange into a complimentary pornograph.”

In the beginning, Burgess liked what he saw—or, at least, he said he liked what he saw—when Kubrick eventually deigned to meet and give him a private screening of the completed film. Burgess didn’t even hold it against the film version of A Clockwork Orange when his wife, repulsed by the film’s choreographed sex and violence, left that screening after a mere 10 minutes. After seeing the movie, Burgess didn’t wait long to tell the press, “This is one of the great books that has been made into a great film.”

Maybe Burgess meant what he said. Or maybe he simply wanted to persuade Kubrick to direct his screenplay Napoleon Symphony. It didn’t take long for Burgess reassess his opinion of A Clockwork Orange the movie.

Buoyed by that first impression, he agreed to join McDowell for a one-week publicity tour of New York City in late autumn 1971 to promote A Clockwork Film, its world premiere set for Dec. 19. The travel-phobic Kubrick remained behind in England, “controlling everything,” said McDowell. The two men’s press day began with a limo pickup, which invariably kicked off with Burgess asking McDowell, “Have you shit today?” McDowell told him yes, at which Burgess launched into a scatological dissertation until their first interview of the morning. That was Monday.

By Wednesday, McDowell noticed a distinct change in his publicity date’s attitude toward Kubrick and his film. “Burgess realized he’d been cheated because he wasn’t paid anything for [the movie] A Clockwork Orange,” said the actor. Regardless of how the film version performed at the box office, Burgess would see no profit points. Worse, “Kubrick went on paring his nails in Borehamwood,” the novelist complained, leaving the publicity chores to him and McDowell. Burgess was even called upon to attend the New York Film Critics’ Circle Awards on Kubrick’s behalf, since A Clockwork Orange had won the best film and best director awards. There at Sardi’s restaurant, Burgess got his revenge when he quickly won the hearts of the assembled reviewers. “I have been sent by God—Stanley Kubrick—to accept his award!” he announced to much laughter and applause.

It had been, by all accounts, a very rough few days of interviews for Burgess and McDowell. On the Today show, Barbra Walters attacked the film’s graphic sex and violence. Four teenagers had recently raped a nun in Poughkeepsie, New York, and it was inaccurately reported that they were dressed like the droogs. Nor had the rapists seen A Clockwork Orange.

Regardless, confronted with Walters’ uninformed rant, Burgess found himself put on the spot. “I was not quite sure what I was defending—the book that had been called ‘a nasty little shock’ or the film about which Kubrick remained silent,” he recalled. “I realized, not for the first time, how little impact even a shocking book can make in comparison with a film. Kubrick’s achievement swallowed mine, whole, and yet I was responsible for what some called its malign influence on the young.”

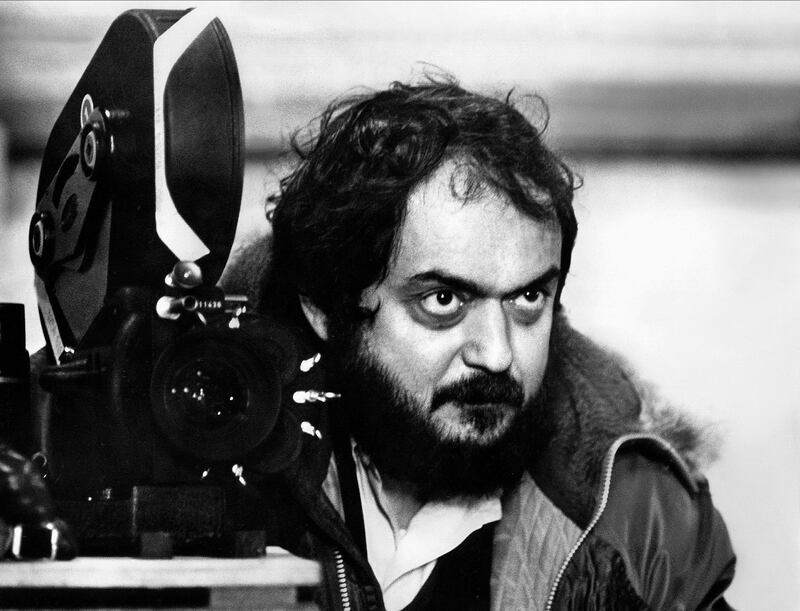

Stanley Kubrick on the set of A Clockwork Orange

AlamyDuring his press chores, Burgess took time to attend a screening of A Clockwork Orange with a paying audience. He wanted to see what all the fuss was about. He wanted to see how New Yorkers were responding and found that “the theology passed over their coiffures.” He was especially dismayed when several people in the audience shouted, “Right on!” at the thug Alex.

For a while, he continued to defend the film, the novel, and himself. In between interviews, he wrote a defense of the film: “Neither cinema nor literature can be blamed for original sin. A man who kills his uncle cannot justifiably blame a performance of Hamlet. On the other hand, if literature is to be held responsible for mayhem and murder, then the most damnable book of them all is the Bible, the most vindictive piece of literature in existence.”

The film received an X-rating in the United States and the United Kingdom, and many newspapers refused to carry advertising for A Clockwork Orange. Kubrick responded to some editorial pages by quoting from Adolf Hitler’s critique of a 1936 Munich art exhibition that called for censorship.

The Bible and Adolf Hitler. Burgess and Kubrick weren’t afraid of going after the big guns.

Did they win or lose the battle? In 1974, Kubrick took A Clockwork Orange out of circulation in the United Kingdom due to accusations that the film inspired copycat rapes and other violent acts. His wife, Christiane, recalled, “When it was released in England, it was blamed unfairly for the increase in crime and there were cries to ban it. We received hate mail and death threats.”

Burgess was one of those who grew to hate the film, so much so that he eventually turned his novel into a play. It included the stage direction: “A man bearded like Stanley Kubrick comes on playing, in exquisite counterpoint, ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ on a trumpet. He is kicked off the stage.”

First edition of Anthony Burgess' novel, A Clockwork Orange

HandoutThis article is excerpted from Robert Hofler’s book Sexplosion: From Andy Warhol to ‘A Clockwork Orange’—How a Generation of Pop Rebels Broke All the Taboos (It Books/HarperCollins). Copyright c 2014 by Robert Hofler.