The Campbell soup cans are there. The piled-high Brillo boxes are there. There are the many faces of Jackie O, and there is Andy Warhol himself colored a livid green in a self-portrait from 1986, his feathery hair jutting out at many angles as if starring in an early iteration of Wicked.

But for all the many must-see familiars in the Whitney Museum’s retrospective, Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again, let your eyes rove throughout this exhibition. Opening this coming Monday, it is the first major Warhol retrospective organized by a U.S. museum since 1989, two years after Warhol’s death.

While you see all that made Warhol famous, look for the Warhol you don’t know. It may make you smile more. It will certainly give you a welcome jolt, even if, as one woman said softly to a companion at Tuesday’s press preview, “I’m just so nervous about tonight and the election results. Every day brings a new disaster.”

Warhol remains so present in our culture it may seem perverse that it has been nearly 30 years since there was a museum show devoted to him. In the intervening years, the media has become its own museum, and Warhol’s images remain thoroughly, eternally, consumed and consumable.

The exhibition, which is mainly situated on the Whitney’s fifth floor, begins with a 1985 quote of Warhol’s: “Everybody has their own America, and then they have the pieces of a fantasy America that they think is out there and cannot see… And you live in your dream America that you’ve custom-made from art and schmaltz and emotions just as much as you live in the real one.”

The quote was presumably chosen as an encapsulation of the Warhol wonderland you are about to enter, where very serious things, like politics, death, and brutality, are given ironic or colorful artistic treatments.

If Pop Art had already begun to satirize the serious on canvas, Warhol took that satire and coated it with glitter and camp, using the subversive eye of a gay artist observing and mocking the predominant heteronormative culture of his time (and without that culture initially realizing it). The social and commercial fevers of the modern world—advertising, celebrity, hero worship, notoriety, White House politics as prime-time entertainment—were colorful putty in his creative hands. Our deities could still be worshipped, Warhol said, but with a wry smile rather than fawning respect.

The wonderful thing about the Whitney show is that it places Warhol’s famous moments alongside the moments you have likely never seen or heard of. It focuses not just on famous faces and glamour but also Warhol’s artistic inspirations and techniques, particularly around abstraction. The show is grouped thematically, not chronologically, and feels less exhausting and more surprising as a result.

Next to the room of his famous multiples is a room of his drawings and early work from long before he was famous, including a wall of fantastic, golden, and ornately designed shoes, inscribed with the names of his heroes: Elvis Presley, Mae West, and Christine Jorgensen.

Warhol began his professional life in the 1950s, after graduating from the Carnegie Institute of Technology, as an illustrator, and here you can see his first commercial experiments with stamps, stenciling, and his signature blotted-line technique.

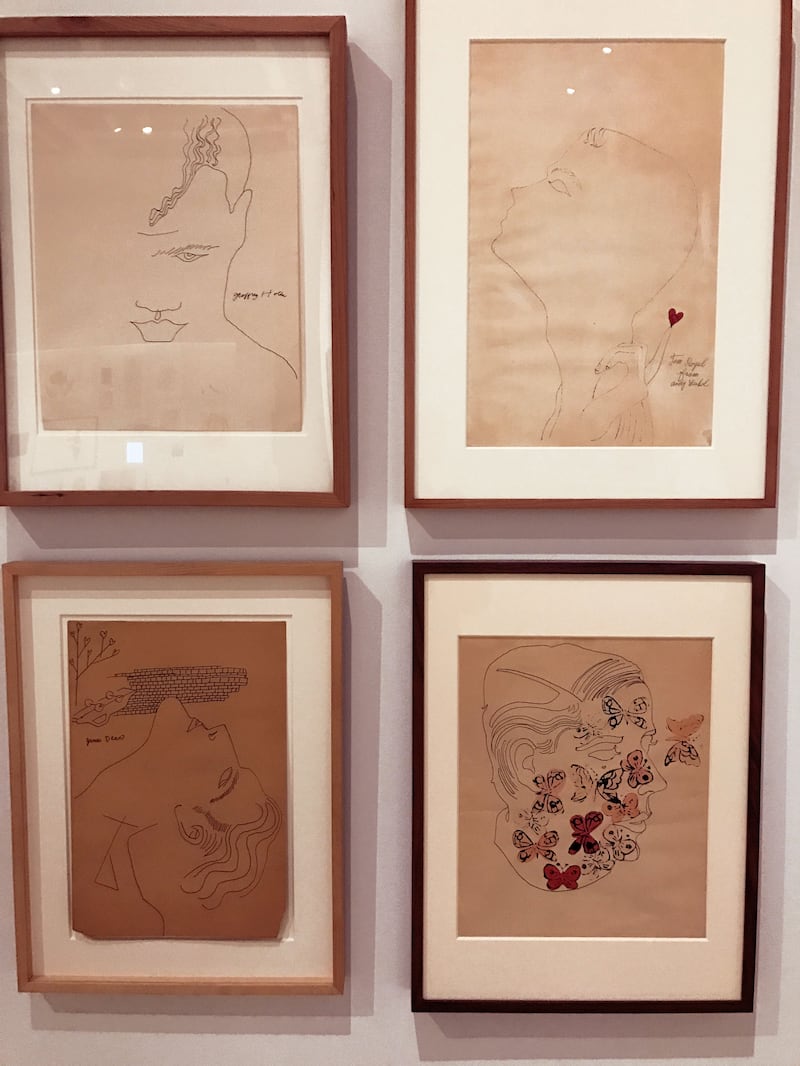

In this fascinating room too are the works of an artist who was gay and beginning to inscribe his sexuality on canvas, at a time when such artistic expression counted as a bold declaration.

Here are Warhol’s line drawings of lovers and friends—their hair and noses and toes; and even one of a boy (possibly Warhol himself) picking his own nose. His sketches of “Geoffrey Holder,” Tom Royal, “Kenneth Jay Lane with Butterflies,” and James Dean, in ballpoint pen, ink, and gouache, are tender and whimsical. There is a crotch and profiles of other unidentified men.

Warhol drew Truman Capote’s features in a sequence of wavy lines in ink, and also captured fashion photographer Otto Fenn, who oversaw a gay salon in the 1950s. The first image we see of his is a still life of the living room of Warhol’s childhood home. Painted in 1948, it features a chair, lamp, couch, and blinds; it looks supremely, weirdly conventional. We see the folk-art influence of Warhol’s mother, Julia Warhola, via a sketch of a cat she did.

The exhibition contrasts the formative and unexpected with the celebrated, now seen up close. One room is devoted to his “Death and Disaster” series. “Saturday Disaster” is a tangle of bloodied limbs, while “Lavender Disaster” features the electronic chair at Sing Sing.

The most shocking, “Suicide,” features multiple images of the body of 23-year-old Evelyn McHale, a bookkeeper who leapt to her death from the 86th floor of the Empire State Building, her body smashed on top of an idling limousine. “Orange Car Crash Fourteen Times” is… guess what.

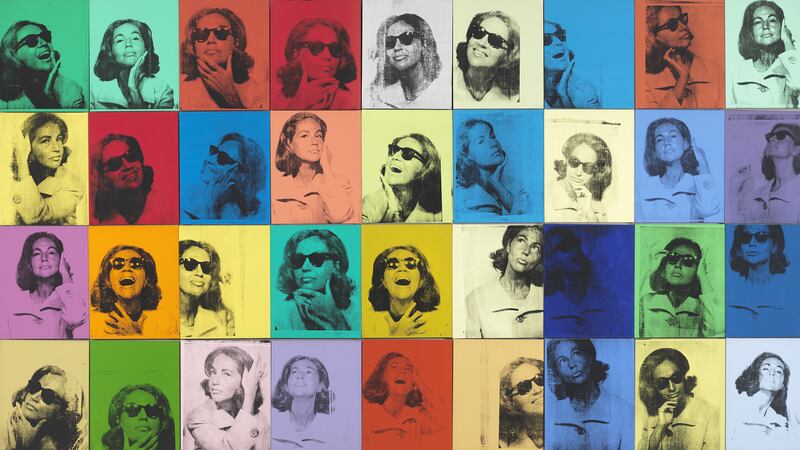

All of Warhol’s artistic technique—from line drawing to photography to silk-screen and installation—is on show. His first major painting commission from 1963, a multiple set of images of arts benefactor Ethel Scull, takes up one wall.

Andy Warhol (1928–1987), ‘Ethel Scull 36 Times,’ 1963. Silkscreen ink and acrylic on linen, thirty-six panels: 80 × 144 in. (203.2 × 365.8 cm) overall. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; jointly owned by the Whitney Museum of American Art and The Metropolitan Museum of Art; gift of Ethel Redner Scull 86.61a‒jj.

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS) New YorkHis beautiful 1972 screenprints series, “Sunsets,” occupies another; a small selection of 632 prints depicting sunsets and likely inspired by his 33-minute film showing the setting of the sun, Sunset, made in 1967. Alongside it is a rare piece of installation art: “Mylar and Plexiglas Construction” (1970), which is like a multicolored mangle or a candy-making machine that more properly belongs in Willy Wonka’s factory.

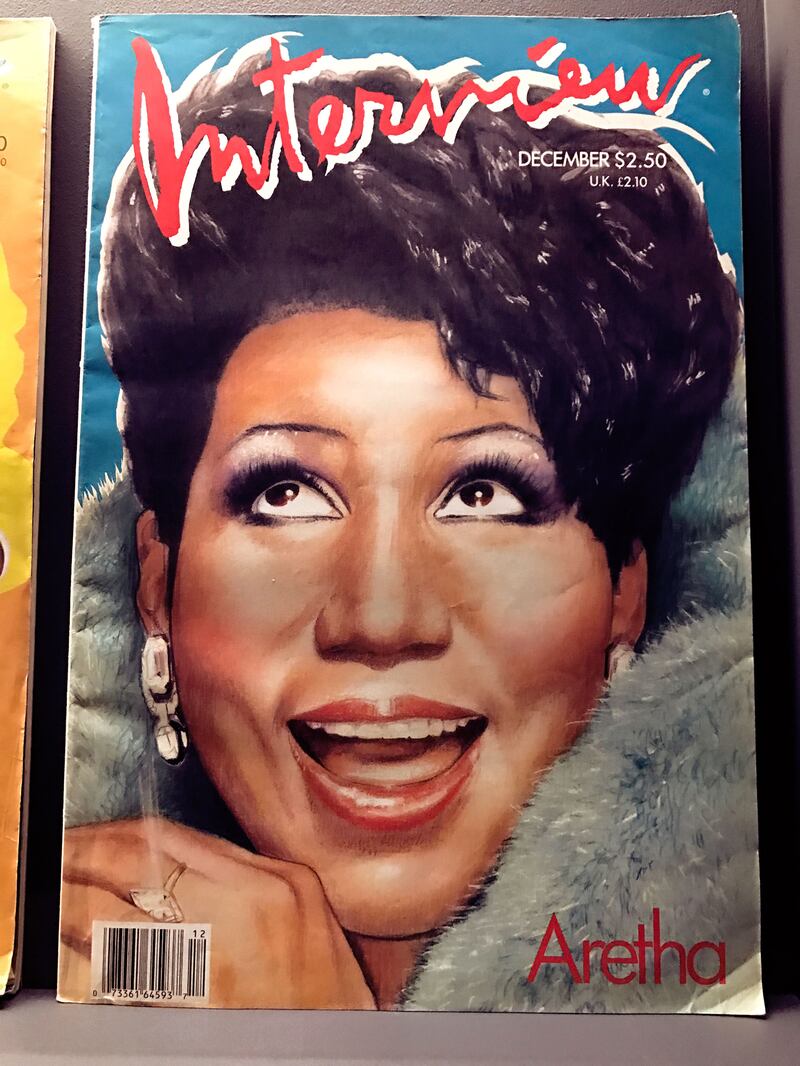

Look at all the display cases. Inside you’ll find the first ever issue of Interview magazine from 1969, when it was devoted to Warhol’s love of underground film, and long before it was a celebrity magazine. Here is his album cover for the Rolling Stones’ Sticky Fingers and the famous Pop-banana for The Velvet Underground & Nico.

In another part of the show you will see another bank of Interview covers from its ’70s and ’80s heyday, featuring Aretha Franklin, John Travolta, and Nancy Reagan. Those who enjoy Warhol’s portraiture will delight in “Eight Elvises,” his famous silvery silkscreen of Elvis Presley in cowboy attire.

Each room emphasizes the breadth of his output. His “Cow Wallpaper” forms the cacophonous backdrop to a room of his flower prints (prediction: This room will become a traffic jam of Instagrammers, which Warhol likely would have loved). The wallpaper was created at the same time as Warhol produced silver, helium-filled pillows in 1966, just as Warhol announced his retirement from painting.

When did he ever have time to go to Studio 54? His designs and influence furnish magazines, books, video, film, and music, and fashion. Because you may have become laissez-faire around Warhol—a peril of artistic ubiquity—you may go too fast by a selection of images from “Flash—November 22, 1963,” which was inspired by the assassination of JFK and the publication of the Warren Commission Report. Moments from that day, plus typed testimony are piled on one another.

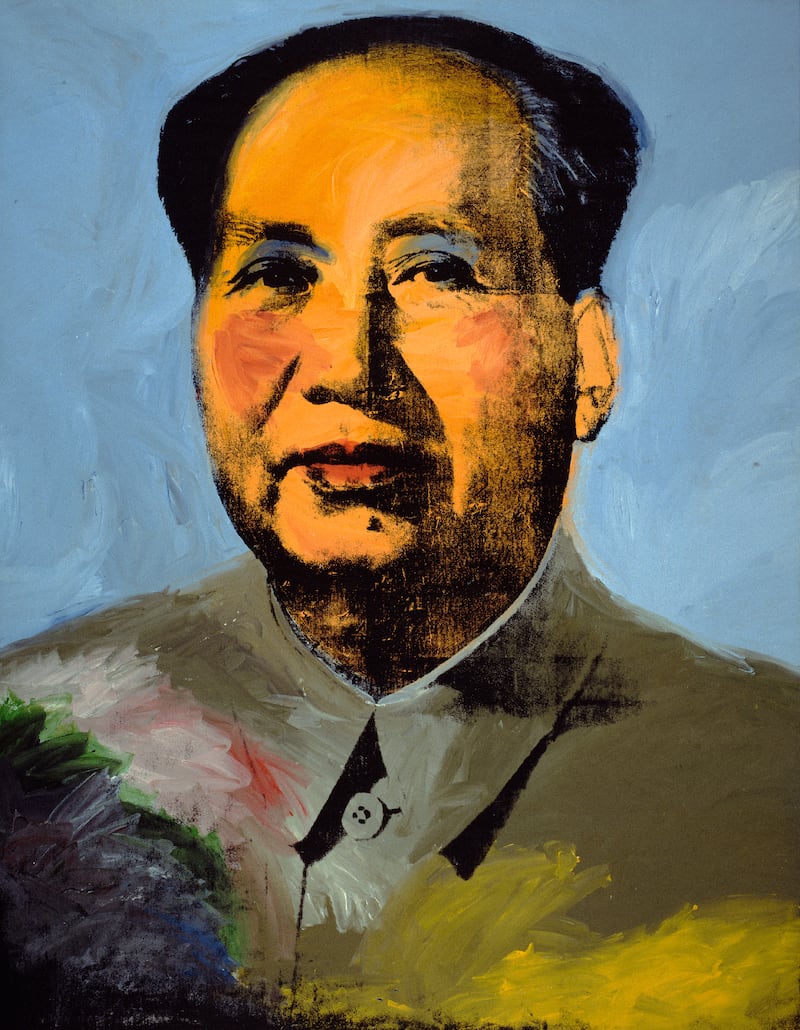

In another room is his portrait of Chairman Mao with red lips and blush cheeks, and adjacent to that a mass of photocopies of Mao that Warhol ordered.

Andy Warhol (1928–87), ‘Mao,’ 1972. Acrylic, silkscreen ink, and graphite on linen, 14 ft. 8 1⁄2 in. x 11 ft. 4 1 ⁄2 in. (4.48 x 3.47 m). The Art Institute of Chicago; Mr. and Mrs. Frank G. Logan Purchase Prize and Wilson L. Mead funds, 1974.230.

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS) New YorkIn this treasure trove it's easy to be dazzled. This gallery-goer wanted more attention paid to the role of assistants and the Factory in this mass of output; how did Warhol work, and what other hands and minds, apart from his own, went into creating a piece that bore his name; what was his artistic process?

The provenance of art, and what made something original, was something Warhol himself playfully addressed in both the themes and production of his work. He once said that “somebody should be able to do all my paintings for me. I think it would be so great if more people took up silk screens so that no-one would know whether my picture was mine or somebody else's.”

Blink and you’ll miss the collection of six self-portraits of Warhol in drag (Warhol with Joan Cusack-ish big hair is a sight to behold) that the artist took between 1980 and 1982. The show also includes Warhol’s series “Ladies and Gentlemen” (1975), which featured transgender pioneer Marsha P. Johnson alongside other trans (and drag queen) models.

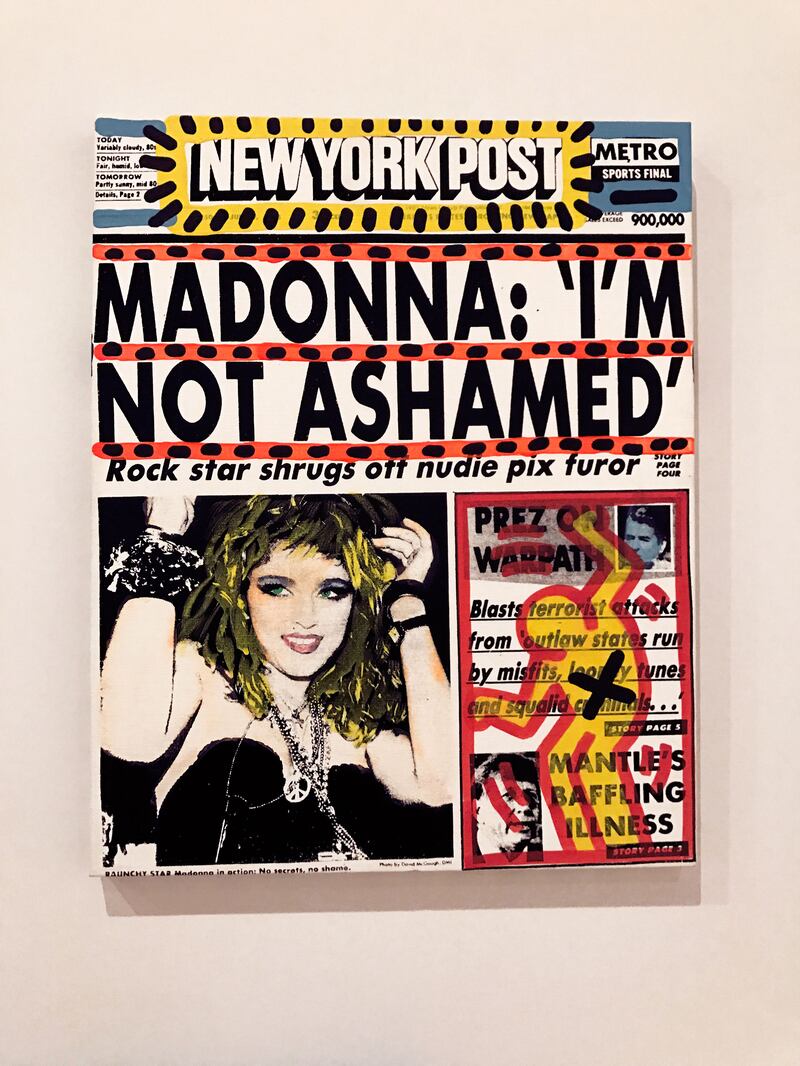

The phrase “ripped from the headlines” buzzes through the spectator’s mind while viewing his recustomized newspaper headlines, like “129 Die in Jet,” inspired by a New York Mirror front page in 1962 devoted to what was then the world’s deadliest-ever air crash. Warhol also ripped from advertising; his multiple Coke bottles are well-known (and present here), but also see his tone-perfect recreations of Coca-Cola posters.

The exhibit takes the viewer through to Warhol’s final years via his flirtation in the early part of the 1980s with that decade’s group of cool New York artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, Julian Schnabel, and Cindy Sherman. There is even a flier for a 1985 show on Mercer Street Warhol held with Basquiat, with both men pictured as if competing boxers. A darkened room is a flickering pleasure palace of Warhol’s short films.

The final room of the fifth floor reveals just how influenced by abstraction and artists like Ellsworth Kelly, Barnett Newman, and Ad Reinhardt Warhol had become. The room is dominated by his Rorschach images and by a 1979 canvas of 63 Mona Lisas disappearing into a soft white nothingness.

In “Camouflage Last Supper,” which Warhol completed in 1986, a year before he died, Da Vinci’s famous painting is overlain by camouflage. The image is a piercing meditation on AIDS, faith, sexuality, and death. Look at its collision of something grand, old and revered, and Warhol’s playful and emphatic intrusion of the new and the shocking.

As you leave the fifth floor, you can linger over a display case of letters, photographs, cards, and personal ephemera, trying to make out the senders and spirit of the billet-doux. Then there are two final images of a white brick wall and another of multiple masks. These are unexpected postscripts to a blockbuster exhibition, quieter artifacts that remind us, vitally, that Andy Warhol was so much more than soup tins, Jackie O, and Brillo boxes—and the loud celebrity that they brought him.

Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again is at the Whitney Museum, from November 12 to March 31, 2019.