The timing of this first Broadway revival of Home (Todd Haimes Theatre, to July 21) in over 40 years is piercing; its author, the playwright Samm-Art Williams, died on May 13, aged 78. To not just get a sense, but also understand the panorama of his life in the arts, and the love, respect, and devotion he commanded, read the testimonies given by friends and colleagues to American Theatre. A resonantly made announcement at the beginning of the show as the lights go down says the show is being performed in his honor and memory.

In this revival of the play, directed with tender nuance by Kenny Leon, the visual constant are rows of corn. They are there when Cephus Miles (Tory Kittles), at the beginning and end of the play, is in his home rural hamlet of Cross Roads, North Carolina. And even when he spends time in “a very, very large American city” the corn is still there, even if not brightly lit.

Home is not a conventional play; it’s the narrated story of Cephus’ life that includes a spell in jail after he refuses to fight in Vietnam, and then many years in New York, lost in a haze of various misbehaviors. His life story is told to us as a rhyme-meets-ballad by Kittles, with Brittany Inge playing Woman One and Cephus’ true love, Pattie Mae Wells, and Stori Ayers as Woman Two. From boxes the two women pull out scarves and coats, and become many other characters—lovers, friends, acquaintances, strangers, and folks along the way, around 40 in all. It’s a virtuosic display of dress-up and swift character sketching.

The poetry and staging combine both expansion and contraction; Home only lasts 90 minutes, yet it feels a grander sweep than that. Arnulfo Maldonado’s clever and simple design matches this; as if seen on a cinema screen, the frames of walls shrink and expand to the shapes of home and church.

Home is a play meets lyrical ballad, where big themes—racism, resistance, identity, and, of course, home—are filtered through the trajectory of Cephus’ life, and the many stories, raw and real and tall and ridiculous, he and Woman One and Woman Two tell. The excellent and expressive Kittles, Inge, and Ayers both relate stories, and the rhythm of life, simultaneously—as if the text is music and they an orchestra as well as actors; as one talks, another may make the propulsive chugging of a train. As the play has it: “Time rushes by./So fast it rushes by.”

Early on the contrasting rootedness and dislocation inherent in Cephus’ life is made clear: “Children of the land./Babies of the soil./Where have they all gone?/With the good teachings. The spiritual souls of their Mother’s and Dad’s. To cities and places far to the North./Changed and rearranged by life and circumstance./That’s where they’ve all gone.”

The text is a mischief-speckled lullaby—beautiful, moving, very funny, then sad; its own journey through a man’s journey. “I love the land, the soft beautiful black sod crushing beneath my feet,” Cephus says, hymning “the warm sparkling drops” of rain that “cover your face and the ground with its sweet blanket of pure wet.”

And then he tells a hilarious yarn about crap shooting “in the white folks section” of the local cemetery “because that’s where all the nice cement vaults were.”

“My lucky vault belonged to Mr. Hezekiah Simmons,” Cephus tells us. “Born July 7, 1877, died July 7, 1957. All those sevens made it lucky. I heard that he was a mean white man when he was living. But in death, Mr. Simmons was definitely my friend.”

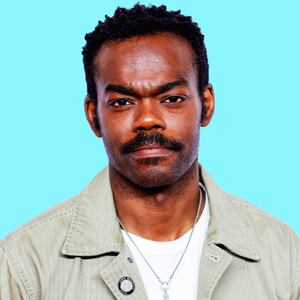

(l to r) Brittany Inge, Tory Kittles, and Stori Ayers in 'Home.'

Joan MarcusHis love for Pattie Mae—“She’s my soft summer day”—remains the constant as he heads north. With that journey away from home, the incantation goes: “Roll, roll. The subway rolls. Take it to the city. Bright lights and party lights. The subway rolls. Escape. Run to the city.” (It had echoes to this audience member of Auden’s “Night Mail.”) Here the vistas of corn recede to a blur of murky cityscapes, a place where Cephus ultimately loses more than he finds.

Woman Two says: “Everybody’s going North man. The city. Move fast. Step out. Good God! Do it! Do it! It will change you. You will be what they call, ‘somebody else.’” This is true, but the city breaks Cephus, not makes him.

The uptown A train can indeed “make you forget these cornfields and hog pens,” but only for so long. The staging and story leads to one place—Cross Roads itself, and Cephus back to capital H-home, with its softened skies, corn brightly lit and ramrod high, and the reborn and re-softened destiny of Cephus himself. The play ends with a twist to warm the heart, and a line that brings a gale of laughter—an assertion of joy and selfhood, and, when it comes to Samm-Art Williams, a vivid legacy to applaud.