Job is one of those rare off-Broadway plays that became a thing—a rave-reviewed, buzzy thing—when it initially ran at SoHo Playhouse in September. Its makers attributed a lot of its startling success to this widely seen TikTok video—another full-hearted rave—by actor Connor Boyd, who posts as “MoschinoDorito” and who has 1.1 million followers. Notably young audiences, especially featuring those working in tech, flocked to see the intense 90-minute twisty thrill ride that is the encounter between therapist Loyd (Peter Friedman) and client Jane (Sydney Lemmon).

The magic of MoschinoDorito may strike again, as Boyd gave the play another rave recommendation, telling his TikTok followers they would suffer FOMO if they didn’t book to see Job for its second run at the Connelly Theater (now, to March 3).

The play begins as a therapy session but, as terrified therapist Loyd (Friedman, who played Logan Roy’s right-hand enforcer Frank Vernon in Succession) eventually tells client Jane (Lemmon, who also briefly had a role in Succession, as Kendall’s onetime paramour, Jennifer), it is actually a hostage situation. When Job opens, Jane is facing Loyd holding a gun, and he understandably seems freaked out.

Jane is a tech worker—her job to sift the crudest, most offensive material and make it disappear—who has had some kind of breakdown, which culminated in a meltdown at work. That meltdown, which saw her standing on a table and shouting, went viral online. From being the judge and jury of online content, she herself has become a notorious online personality. She really doesn’t want to be in this room; having therapy is merely a box-ticking exercise in her mission to get her job back.

Boyd told The Daily Beast of the impact of his post, “It’s really cool. It’s hard to gauge what your impact is when you’re on TikTok, so seeing it materialize into ticket sales was really exciting. I hadn’t seen a play in forever, and I have a friendship-relationship with my audience. I know some will he happy to hear about these things, and be excited about going to see the thing I am talking like, and then comment, ‘Thank you so much, that was really fun. I got a lot out of that.’ So I take real pleasure in doing things like that. It was definitely a milestone, to have the impact I had. I didn’t expect it.”

Job made such an impression, said Boyd, because of “the intimacy of the space, and how intimate, in-person, communal artistic experiences are becoming rarer and rarer. I was watching world-class actors, I was sitting yards away from them right there watching them. You could hear a pin drop. I just think younger people don’t understand that acting is not just for cameras and television. Live theater is a total performance, and when you go see a performance of a play it is fixed in that moment of time and place forever. When we stream television shows we are all watching the same performance. In live theater you don’t know what’s going to happen, or how the performance will go. Inevitably the end work of that performance that night is completely unique.”

To say much about the plot of the play would be to spoil its major twists, but—as this author said in The Daily Beast’s review—its author Max Wolf Friedlich and director Michael Herwitz thread the strange dance between the two lead characters with a steady build-up of revelation and tension. The performances of Friedman and Lemmon are riveting. Lemmon’s Jane is both sharp and fractured, a coiled spring of acid all-knowingness, whose fury means we, like Loyd, fear what she is capable of.

We hear fragments of her personal story, alongside her holding forth on the dysfunction of the internet, and the generational clash she sees between the young of today and Loyd’s Boomers.

Jane’s job as a content moderator means she has seen the worst of the world, she says. “The phone is never the problem—people do bad things, not phones,” she insists. She has seen “car crash compilations, mass graves, heroin overdoses, a website for strep throat fetishists. People eating glass, people sticking glass up their assholes and vaginas.”

The audiences were enthralled to see how the therapy session turned out. Of the impact of his post, Boyd told The Daily Beast, “It was as completely surprising to me as I’m sure it was for those behind the play. The ultimate view and like counts weren’t as high as what I would consider a hit on TikTok, but for those people who reacted to it, they seemed to take action about going to see it. Usually my content is comedic, so if I am being straightforward and genuine it isn’t always guaranteed to be as algorithmically successful as the more humorous posts, so it was really surprising to see so many people take action about seeing the play.”

The response to his post has encouraged Boyd to consider declaring his love of things in general, and to see more theater in general. He ended up seeing Job twice at SoHo Playhouse, and may see it at the Connelly. If so, will he post another Tiktok? “Ha, I don’t know. Maybe a third time will be even more impactful.”

Just before they headed to the Connelly for dress rehearsals, The Daily Beast spoke to Friedman and Lemmon (who is Jack Lemmon’s granddaughter), about performing the intense play, its surprise success, meeting on Succession, and how every night performing Job feels different.

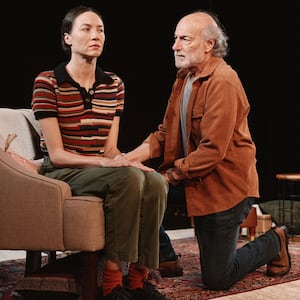

Peter Friedman, left, and Sydney Lemmon in 'Job.'

Emilio MadridPeter Friedman: We’re reinvestigating the play right now, so it’s like shaking off some old muscle memory and looking harder at the play.

Sydney Lemmon: It feels as if the world has changed, and continues to change—so the play feels kind of fresh given the circumstances of life now. It’s exciting to dig back in.

Peter: We’re not redoing major parts of it. We’re taking a few seconds to clock hearing things differently during the therapy session itself—things that might have driven through before.

Sydney: What he said! It’s a tricky balance, I would say. We have a specific place to get to in the play. We’re negotiating discovering new things. We haven’t welcomed a new audience yet, and we’ll see how it works.

Peter: All these things we might take out at the first preview. But it’s like we’re hearing the play anew.

Sydney: Honestly it all feels fresh. I don’t know why. It hasn’t changed on the page.

Peter: We don’t know where it’s going to go. That’s the trick of doing something over and over. That’s what’s hard. You have to do it as if it’s the first time over and over again. Then it’s always a surprise for us.

Sydney: At the beginning, the difference between them is that Jane has an idea of Loyd, and Loyd has an idea of Jane.

Peter: No, not beforehand.

Sydney: Jane has a concept of who this guy is, but when she gets there she’s confronted with something—then has to backpedal quickly to have the session she wants. Playing Jane and Loyd is like running two trains in tandem.

Peter: It sounds artsy-fartsy, but I don’t know of another play where you have to work two trains at the same time. We’ve learned in all our training that there has to be something our character has to achieve, and it sure looks like there are two things going on here for the two characters. It’s very unique. I’ve asked all my acting friends who come, “What is Jane’s objective?” People have different answers. It’s a double deal. What does she know about Loyd? Is it true?

Tim Teeman: When I saw it, there was a charged atmosphere in the small SoHo Playhouse space from the start—from when it seems Jane is taking Loyd literal hostage, before the play takes its various twists and turns.

Sydney: Oh, that’s nice to hear.

Peter: We can’t be too aware of that, we have to stay so focused.

Sydney: We could feel the audience 100 percent, but we were engaged with something that is very taut. I can’t break focus for a second. If I do, it takes me a really long time to get back into it.

Peter: There’s no benefit to breaking focus. When I would speak with friends afterwards, they were very complimentary, but you think, “Oh, they’re friends being nice.”

TT: It’s intense to watch. Is it just as intense to perform?

Sydney: Actually, it was a really fun rehearsal process. We had a lot of laughs. We took the work seriously, but I think we did it in the lightest way possible. Every night we do the play, then it’s over. We have a nice chat and go on our merry way. We let the dark stuff be the dark stuff, and try to keep everything else feeling nice.

Peter: We’ve been re-rehearsing in a very well-lit rehearsal room with people a few feet away—and it’s not a whole lot of fun. To be honest, we’re dying to get back to a dark theater stage to feel that tension again.

Sydney: The play can really play like jazz. Whoever the actors are in it will find their own way through it. In the first iteration we found our own music. We also had cerebral conversations as we hacked it out. Max (Wolf Friedlich, the playwright) was very generous to work with. The rehearsals and then doing the play moved everything so far from the brain into the body that when started re-rehearsing it last week I couldn’t put together what I thought about it. The play lives in our bodies now. We need a dark room to let it go, to let it be free.

Peter Friedman, left, and Sydney Lemmon in 'Job.'

Emilio MadridPeter: The space, the privacy, is important, and I look forward to being on a podium above everybody else in this dark room, and the lights on us, so we can’t see anything but each other and we’re alone.

Sydney: This is a therapy session, and then there is also the thing that Loyd is being held hostage.

Peter: Loyd is confined.

Sydney: Jane has changed so fucking much—pardon my French—as a character from where I began with her.

Peter: She does almost every day. Sydney finds new ways of doing her final speech every time we do it. I always think, “Bring it on.”

Sydney: That’s so nice, stop it. The major challenge of playing Jane for me was bringing her out enough to fill the space of the theater. Initially, I had so many judgments about what it is to be Gen Z, millennial, techy person. My instinct was to make her quiet, to take her in, in, and in. I had to balance those good impulses with the ability to craft a theatrical performance reaching out. People talk to us about it as a generational divide Boomer/Millennial play. Peter and I never spoke about that. We kept the focus on what was happening in this therapy session.

Peter: I saw Loyd as a character immediately, and having lived those years as he had, I had my idea of what he would be.

Sydney: We’ve had a lot of variations in audiences. Sometimes people laughed boisterously at the beginning. The writing is funny and we were anticipating it. But sometimes the laughter continues long past a point where anything funny has been written or said. At those moments Peter and I are communicating telepathically, saying to each other, “Why the hell are they laughing right now?”

Peter: It feels like the play leaves our control at moments like that.

TT: It’s ironic, given the play’s themes, that a TikTok video helped drive so many people to the theater. Lots of young people went, and tech people?

Sydney: We felt the excitement. We knew the houses full, and that was astonishing.

Peter: And, as you say, young people too. We came in one day a week before opening and were told we’d sold out for the entire run—and then they told us about the TikTok video. It was crazy. At opening night, a famous actor came with his wife and daughter, and afterwards the actor said all the good things. Then their kid pushed through, and just had so much to say.

Sydney: I really loved whenever who worked in tech came to see the play. They would say, “Oh my god, I know people who do Jane’s job under similar pressures.” Or: “This woman freaked out and came to campus with a weapon too.” Therapists told us about the time a client bought a weapon to a session. So many people told us stories like that. You really wouldn’t expect it. This play is so extreme, the last thing you would anticipate is people saying, “Oh, I’ve been in that situation before.” But many, many people did, and it was a real privilege to get to hear their stories, and appreciate how they felt reflected in the play.

TT: Has the play affected how you both use the internet?

Sydney: Yes, I now have a 15-minute maximum cap on how I use Instagram. I don’t use TikTok. I stay off my phone. I was trying to do this generally, so I’m not sure if it’s all to do with the play. Lots of people, whether they have seen or read this play, feel that way.

Peter: I do old-people things on the computer—read, watch an old movie, that kind of stuff.

Jeremy Strong, left, and Peter Friedman in "Succession."

HBO MaxTT: Before doing the play, did you both meet on Succession?

Peter: Actually, yes. We arrived on the same plane, and met in the lobby in the hotel in Dundee (for the episode of the same name, the eighth episode of the second season, where the Roy family fly into the Scottish city for a party to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Logan—played by Brian Cox—founding Waystar Royco).

Sydney: We were both checking in, and just this last week on my iPhone the “memory” popped up of Peter and wife Caitlin (O’Connell) walking through this beautiful castle in disrepair, falling apart on the edge of a cliff. It was like, ‘Look, we were in Scotland together.’ Our characters didn’t have any scene work together, besides a big banquet scene where there were like 50,000 people there for what was supposed to be Logan’s big party.

Peter: All of Dundee who wanted to stand around in party dress were there that night.

TT: What’s it been like to see the show clean up on the awards circuit for what was its final season?

Peter: I am very glad to have been part of it, to be part of the tapestry. I got lucky. It’s… alright. You feel like you get reflected attention while it’s on. People see you on the street. Once at Columbus Circle (in New York City), some person stopped me at the light while I was waiting to cross, then another lady said something, then a driver shouted something. I was like, ‘Watch the lights people!” If you go to Wholefoods, it’s really a thing. If I go to Wholefoods, I wear a mask. (He laughed) Wholefoods customers are the Succession demographic.

Jack Lemmon in drag, left, and Marilyn Monroe during a scene from the movie "Some Like it Hot."

Richard Miller/Getty Images/Richard Miller/Getty ImagesTT: Sydney, your grandfather was Jack Lemmon, and your dad Chris Lemmon is an actor. Were they very encouraging when it came to acting?

Sydney: No, they tried to keep me out of it.

Peter: Really?

Sydney: Yeah, they said, “Don’t do it. If you can do anything else, just do that.” But I loved it. It started with school plays, which led to acting training and education.

TT: Is being “Jack Lemmon’s granddaughter” a burden if you’re an actor yourself?

Sydney: It is not a burden whatsoever, but rather a delicious, sweet feeling.

TT: The space at SoHo Playhouse was small, compact. That size and intimacy added to the atmosphere of the play for the audience. The Connelly is a little bigger. And a Broadway house would be a bigger stil.? Might the atmosphere of the encounter between Jane and Loyd be lessened if the theatrical spaces get bigger?

Peter: I think you’re right. I don’t want to hurt whatever the producers have in mind, but I wouldn’t want to do it in a larger house. I’ve seen stuff in larger houses which have succeeded in smaller ones, and you have to use sitcom energy to fill the space. I don’t think it’s what I want to do.

TT: What is it like to perform? There’s just two of you. Does that entail a level of trust that is different to performing as part of a large company?

Sydney: We come on stage. The lights go up, and we don’t leave till the lights go down. It’s just the two of us. So far we have been fortunate, knock on wood, that in the first run, we never got into seriously hot water, losing our place in it. That fear keeps me up at night. I’m grateful it didn’t happen the last time, which is why I am knocking on wood now. I feel as though, no matter what happens, I have complete trust in doing this thing with Peter—he can always get us back on track.

Peter (looking askance at Sydney’s faith in him): God!

Sydney: Seriously, I feel very, very safe with you as my partner in this—and feel like we can do it, no matter what.

Peter: God, OK.

TT: Do you ever surprise each other during a performance?

Sydney: Oh yes. I feel like we are listening to each other, and hearing it and finding it new every single night. That’s how it feels.

Peter: That’s the deal.

TT: Did you have any memorable audience responses at the SoHo Playhouse?

Sydney: I loved it whenever we would hear an “Oh shit,” or gasps at those twists, or shocking moments.

TT: Do you hope the audience may leave feeling not entirely sure what is true and what isn’t—that the ambiguities of the play win out?

Sydney: Yes, more than, “She was definitely this or that,” or “He did this or that.” We hope people leave thinking, “Well, where do they go from here?” and “Who are these people?”

Peter: Sydney and I try to live moment to moment in this play. For us, like the audience, it’s a real-time experience. We know the script, but we are never sure what’s going to happen next. If you said to me, “What happens after this moment?” I couldn’t tell you. So, we just get on…

Sydney: Yes, and go for the ride.