One math lesson endlessly demonstrated in Chicago's tougher neighborhoods is that the tiniest shift in a gunman’s aim translates to an ever larger change in a bullet’s trajectory that can make the difference between life and death.

Sixteen-year-old Michael of the South Side learned this firsthand as an innocent bystander on Sept. 10, moments after he and his classmates left Chatham Academy, which had just completed an active shooter drill such as have been conducted in schools everywhere following the carnage at Columbine and Virginia Tech and Sandy Hook and Parkland and too many other places.

Unlike those other schools, the far greater danger for kids of Chicago’s less affluent neighborhoods is the streets outside. The threat remains constant and unnerving even though police recovered more than 5,000 illegal guns in the first half of the year and violent crime is in decline. Homicides are down 20 percent so far this year. Shootings are down 18 percent.

But clearance rates, essentially how many crimes result in an arrest, are also down, to less than 16 percent for homicides, less than 6 percent for shootings. A recent study suggested that as many as one in three young people carry a gun on the South and West sides despite the continuing police effort. The motive seems to be largely protection; a third of those who are packing said they had been shot at or fired upon.

The continuing threat in the streets outside Chatham Academy took the form of a gunman who suddenly appeared from a car with a T-shirt pulled up to partly conceal his face. One of the bullets he fired tore through the likely intended target and into Michael's back. A shift in the trajectory of less than a centimeter would have sent the slug through Michael’s aorta with surely fatal results.

But the slug just missed the critical artery and he lived to teach a lesson for the whole country about maintaining the trajectory of your life even when it can be taken from you at any moment. He remains in an environment so dangerous his mother prefers not to publish his last name, but he continues on as a smiling model of courage and resilience and principled priorities in these callow times when so much seems fractured and devalued.

The Chicago news media duly reported the incident, noting that the shooting in which he was wounded had been preceded by another shooting four blocks away two a half hours earlier. A gunman had fired upon a 21-year-old and the trajectory of that bullet had sent it through the man’s neck, killing him.

It was this earlier gunfire that caused the school to go on an actual alert. The media had not failed to recognize the irony of the school's principal going from concluding a pre-scheduled active shooter drill to making an announcement over the PA system that students should be cautious when departing and head directly home. The message was repeated by the security guards posted at the exits.

“There's a lot of shootings going on, we want y'all to be safe," one guard was quoted by the Chicago Tribune telling Michael as he left. "We want y'all to go straight home. Make it back tomorrow safe and sound."

Outside, Michael saw a longtime family friend and another man he knows in a car. He called out to them for a ride, but the the car was already pulling away. He was starting home on foot when the gunfire erupted and people started running.

“I’m like, ‘Did I get shot?’” Michael would tell The Daily Beast .

As the Tribune would report, two other students were also wounded and all three survived. The paper interviewed Michael and his mother, Edye Brown, as he recovered at the University of Chicago Hospital.

Michael spent five days in the hospital.

Courtesy Edye BrownBut the Tribune and the rest of the media then understandably moved on to subsequent shootings, including one on Oct. 8 where a bullet’s trajectory sent it through the leg of an 18-year-old and into the neck of 2-year-old Julien Gonzalez, leaving him beyond saving.

Michael recovered to a point where a doctor instructed him to raise both arms above his head and removed a drainage tube from his chest. He had been shot was on a Monday and he was discharged that Friday. He had no doubts at all about what he would do when the following Monday arrived.

“I’m like, ‘I’m going to school,’” he would recall.

He voiced his top priority.

“School has always been number one with me,” he said. “When it's time to go to school, it's time to go to school until I graduate.”

The white sneakers he had been wearing at the time of the shooting were bloodstained, but he had a pair of red and black ones that went well with the red and black Chicago bulls hoodie and light blue denims he had on as he emerged from his home that Monday morning, resuming his life exactly a week after it had come within less than a centimeter of ending. His back-to-school outfit was completed by fresh bandages, front and back.

“They told me to change it every three days,” he later said to The Daily Beast.

His mother came along and they went to the principal's office upon their arrival. The principal asked when Michael might be ready to resume his classes.

“Today!” Michael replied.

Michael had only been at the start of the second week of school when he was shot, but he had already developed a fondness for Chatham Academy.

“I just like the school,” he told The Daily Beast. “My first week, the teachers were all connecting with me.”

The teacher in the last class in his schedule had asked Michael what he wanted to do later in life. He has always loved vehicles and he told her he hoped to get a CDL, a commercial driver's license that would permit him to drive everything from trucks to buses. She presented him with a surprise on the fateful second Monday of school.

“She printed up a big packet, the whole rules and regulations for getting a CDL licence to take the test!” Michael later said.

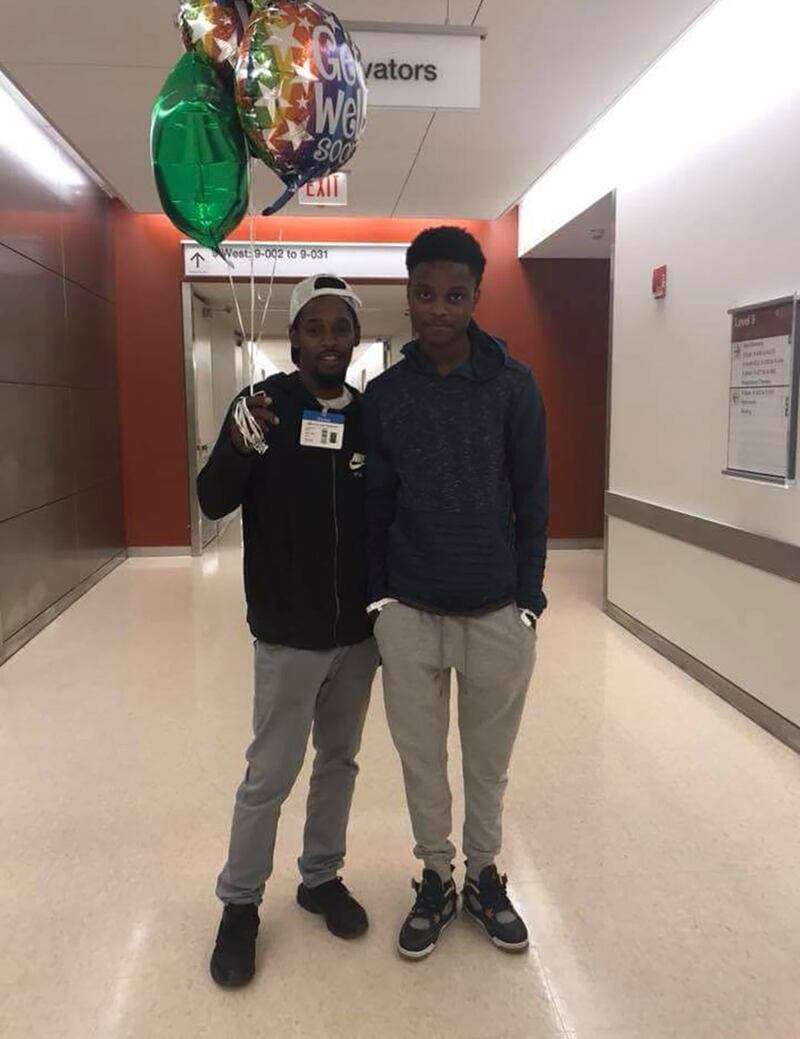

Michael and his stepdad get ready to leave the hospital.

Courtesy Edye BrownA good friend named Porcha offered to carry the packet in her purse, as Michael did not yet have a backpack. He otherwise likely would have had the packet with him at the time of a shooting not long after this last class of the day let out. The bullet that pierced him from behind might have struck the study materials for his avowed goal along with the backpack. The trajectory might have been shifted a fatal fraction of an inch and robbed him of any future at all.

Porcha was there when the gunfire erupted and he had called out to her.

“I’m hit! I’m hit!”

She was at his side in the cafeteria as he sat on a table and removed his shirt

“I was looking down at the bullet hole,” he would recall.

He eased back on the table.

“[Porcha] shaking me, she screaming for somebody to call an ambulance,” he would recall. “She’s telling me like open your eyes, breathe!”

He would later say that his ears seemed to close up and sounds became fainter as Porcha kept calling him to him.

“That girl, she wasn’t going to let me die,” he would later say. ”Her tears be on my face.”

He felt as if he were beginning to fade away.

“My eyes was open, but it was getting dark,” he would remember. “It was getting real dark. I was getting short of breath.”

But even as all else dimmed, he suffused with an inner brightness. He would recall speaking determinedly to himself as the person who knew him best:

“I’m not going to let this end my life. I know what I'm trying to do. I know I'm doing the right thing I know I'm going to school. I’m not going to let this just stop.”

The school had a zero cell phone policy, but Michael had retrieved his on the way out. He nonetheless missed a text his mother sent from a laundromat several blocks away. She had been doing a wash while off from her job as a nurse.

“Hey son, not sure if you got your phone... I just got word that there has been some shooting near your school.”

The mother’s cell phone rang and one of the paramedics who had responded to the school told her Michael had been wounded, but his vital signs were good. They put him on the phone.

“Mom, I’m OK, but I did get shot in the chest,” he said. “But, I’m OK. Don’t worry about me. The paramedics are taking me to the hospital.”

The mother would recall, “He’s just talking to me like nothing's happened. I’m just happened him with questions. I’m just like freaking out at this point.”

Brown raced to the University of Chicago hospital and remained with her son over his five days of recovery. He made the declaration that showed his spirit had grown only stronger.

“I’m like, ‘I’m going to go to school,’” Michael would recall. “She was like, ‘It’s up to you.’”

Michael returned to Chatham Academy after recovering from the gunshot wound.

Courtesy Edye BrownHis bravery inspired the same in Brown as she overcame a mother’s natural protectiveness when her child has been nearly killed.

“He definitely had the courage,” his mother later told The Daily Beast. “He had the the courage for both of us. I don't think I would have been ready.”

She added, “No parent wants to experience something like that. All of this violence and there’s reasons behind it. And he’s just trying to get his education. That definitely just tears me up.”

She remained on what she called ”an emotional roller coaster” at the thought of her son and so many other children living under constant threat.

“Fearful of going to school, fearful or leaving school, trying to get home,” she said.

The mother in no way faulted the Chatham Academy for what had happened. She noted that the school had taken whatever precautions it could after the nearby shooting earlier in the afternoon. She wondered why the police had not posted even one officer outside the school when it let out.

“No cops,” the mother said. “No cops at all.”

In the meantime, the police made it known they had stopped two suspects near the scene and taken them into custody. Michael and the mother learned that the two were the family friend and the other man in the car he had called out to and seen drive away from the school just before the shooting. The police continued to hold them for days despite assurances from Michael and his mother that the supposed suspects could not possibly have been involved.

The two were finally released and the case went unsolved in a city where the police clear up less than 6 percent of nonfatal shootings, less than 16 percent of homicides. But two cops did have time to make a U-turn and pull over Brown and her husband as they drove through the area a week later. The cops told the couple that their car’s license plates were expired.

“I had to tell them, ‘Are you kidding me?... My son got shot a week ago. Where were you guys then?’” Brown would recall.

Back at school, Michael continually reminded people that he was not an invalid and needed no special treatment.

“I’m still like the same person,” he told The Daily Beast. “You don't have to act like that opening doors for me. I had to tell them, ‘I’m all right. I’m OK.’”

The hospital had sent him home with pain medication, but he abstained from using it even when his still healing wound hurt.

“I haven’t even took one of them pills yet,” he reported.

He did not need to be reminded how lucky he was that nothing had caused the bullet’s trajectory to change ever so slightly.

“I realized I really was thanking God for real, for real,” he told the Daily Beast. “The whole situation could have went the other way. It could have turned out so different.”

The inner brightness that had suffused him when eternal darkness loomed now enabled him to see his way even more clearly than before.

“I opened my eyes,” he said. “I realized a lot of things. I valued my life more.”

Meanwhile, Porcha had given him back the packet the teacher had printed out. He was ready to start studying for his CDL and be ready to go to work after he graduates.

“I can’t wait until I start getting a job,” he said.