At the beginning there are display cases containing an early native’s ceremonial war club, some faintly inscribed parchment, and a slice of pipe that formed New York’s original water system. At the end there is a bejeweled Judith Lieber evening purse and a copy of New York magazine proclaiming, “Bikelash.”

The 400-year story of New York, as told by the Museum of the City of New York’s latest exhibition, NY at Its Core, is that of a proud, roiling island—bubbling with commerce, cultural melting pots and clashes, economic polarities, and era-defining incident and drama. The museum posits that “money, diversity, density, and creativity” drove the formation of New York and continue to drive it today. Screens in both rooms map the eddying evolutions of the city’s population density.

The exhibit, made up of 450 historical objects and images, begins and ends with the water that surrounds Manhattan. In two galleries, split up into sections telling the stories of different eras, the visitor travels from 1609, when Henry Hudson first sailed up the river that would later take his name on Manhattan’s western flank, to 2012, the year of Hurricane Sandy.

ADVERTISEMENT

Along the way, it tells an astonishing urban story, with a huge cast of characters—from Hudson to Peter Stuyvesant to Emma Goldman to Andrew Carnegie to Jay Z—who have influenced not just New York but the wider world. As the song goes, if you can make it there…

In 1609 Hudson was seeking a route to the spice markets of Asia, we read, “but recognizing the natural resources of the area, a land rich with furs, fish, and plants,” he sailed into what was then the land of the Lenape people, and stayed. Over the next few years, the island became a commercial seaport “embedded in a global Dutch trading empire.”

The Lenape tribe had colonized the five boroughs for 6,000 years before Hudson arrived, but by 1700 only small groups remained—and this after a series of brutal squabbles over who owned the land of Manhattan Island between Native settlers and a growing European population.

The reverberations of history with today are inescapable—and perhaps inevitable; cities are palimpsests, after all—over who colonizes which parts of Manhattan; while Dutch Calvinism became the official belief of “New Netherland,” other beliefs were allowed to exist “quietly and legally.”

The English seized New York in 1664, transforming it into an international port. If immigration flourished under them, along with religious plurality, so did violent slavery. Despite the threats of disease and fire—on display is an 18th century leather fire bucket, and the certificate of appointment for a fireman from 1787—the population grew to more than 21,000 by 1771.

The exhibit makes clear that New York’s history has always been a rollercoaster. In decline during and after its British occupation, it rebounded to become the nation’s most populous city and busiest seaport by 1810; the city’s grid system was first configured in 1811. Slavery officially ended in New York in 1827.

Fascinating objects—snuff boxes, a shoe worn to George Washington’s inaugural ball—stud the tide of history. In 1784, Alexander Hamilton helped found the Bank of New York, the city’s first bank and only the second in the nation. By 1825, Wall Street had 11 banks and 29 insurance companies; the port exported the produce of the farms of the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island, Long Island, and New Jersey.

By the 1830s civic leaders began to plan roads, parks, and plans to expand the city, which was assailed by a cholera outbreak in 1832. By 1855, over half of the population of 630,000 were immigrants, the highest percentage in New York’s history. In the middle of the gallery are fun, interactive swiping boards, picking out historical figures as various as the beaver, “New York’s first export,” and Hudson himself.

In history, as today, the phenomenal amounts of money swirling in the city meant that the distinctions between the very rich and the very poor were always stark.

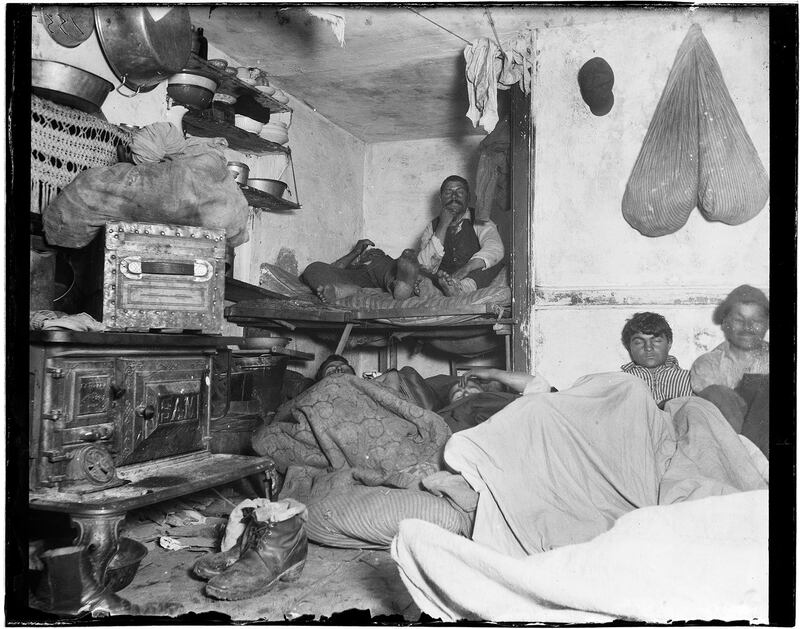

In the 19th century, while the rich built homes on Fifth Avenue and funded opera houses and museums, and a “Ladies Mile” of swanky shops formed between Broadway and Sixth Avenue and 15th and 24th streets, on the Lower East Side, working-class businesses—umbrella makers, hot corn sellers—thrived. In Lower Manhattan there were tenements and slums, documented in the photographs and essays of Jacob A. Riis.

The exhibit makes clear how another influx of immigrants made New York even more diverse in the late 19th century, with newspapers catering to particular communities, and an even more dizzying cultural melting pot of political alliances, jokes, language, food, and images.

Areas like Chinatown came into being. Coney Island became a fun-land escape, and the Bowery known for its cultural vibrancy, with uptowners and out-of-towners coming to gawk and “slum it” there. In the early 1900s, postcards showing “exotic” Lower East Side life were on sale.

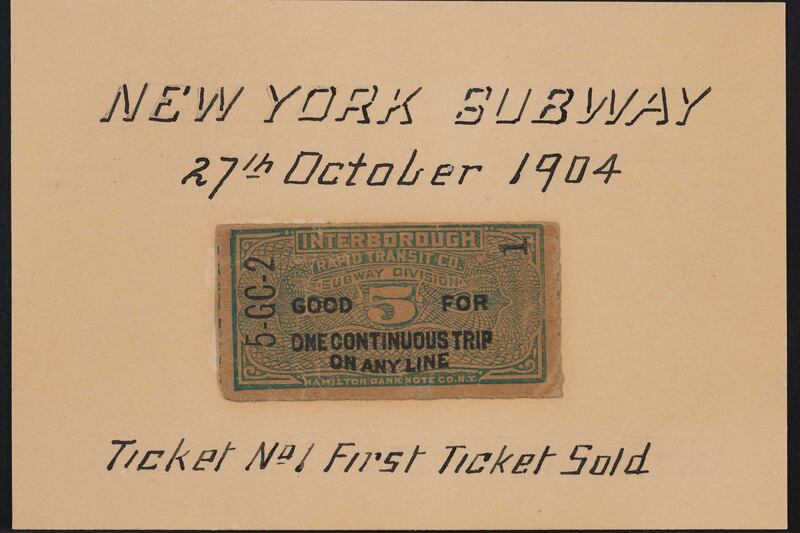

Transportation innovations, like ferries and the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883, changed life and mobility dramatically (there are materials and tools from its construction on display; look out for Erica Wagner's book on its chief engineer, Washington Roebling, which will be published in the US next year).

Three years later the completed Statue of Liberty came to define New York’s status as an inspiring, stirring gateway to America.

The second gallery, filled with the sounds of the city—honking horns, drills, and sirens—takes up New York’s story from 1898. If the cultural vibrancy of New York increased exponentially (by 1930, 200,000 African-Americans lived in Harlem), so did its sharp social divisions.

For all its image of a city of encompassing opportunity, the centrifugal economic force of New York, and the discrimination operating alongside it, meant the haves had even more and the have-nots even less. In the display cases we see a flapper dress, a pair of tap shoes worn by Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, and a speakeasy recipe book, and later Abstract Expressionist art, and a trumpet owned by jazz musician Roy Eldridge.

The exhibit analyzes the effect of the Depression and the New Deal—we see protesters holding rats at one rent strike protest—and how the eradication of the slums of Lower Manhattan dovetailed with the building of such landmark projects as the Twin Towers. It looks at the efforts of successive mayors to imprint their visions on the city, and key figures like planning scion Robert Moses and his nemesis Jane Jacobs, and highlights momentous protests, like the Stonewall riots of 1969.

The fascinating statistics are occasionally jolting. In 1950, 917,000 New Yorkers worked in manufacturing and 430,000 in the port; by 1980 the first figure had dropped to 597,000 and the second to just under 200,000. During the 1960s the city lost a fifth of its factory jobs.

In the 1970s, the city’s social divisions became so pronounced they became enshrined in movies like Death Wish and Taxi Driver. One’s experience of it, of course, depended on where and how you lived. Other display cases hold the treasures of Studio 54—a 1978 guestlist includes Liberace, Ringo Starr, and Lindsay Wagner—and CBGB.

The 1977 blackout was heralded by a Time magazine cover headline: “Once More With Looting.” You can see Milton Glaser’s original concept sketch for the “I Heart New York” campaign (1976). The viewer surfs from beautiful clothes and expensive trinkets to a poster for a fundraising AIDS dance-a-thon.

There’s a photograph from a 1988 demonstration by residents of the storied Christodora building (recommended: Tim Murphy’s novel of the same name), and a Donna Karan-designed Barbie doll. The fruits of public-private partnerships segue to the exhibit’s only piece of 9/11 memorabilia: a twisted and battered sign from the World Trade Center’s PATH station.

The exhibit ends with a series of unresolved questions: How should the city’s money be spent; who benefits from new developments; and who is able to live in the city? The questions were made all the more urgent by Hurricane Sandy, “a natural disaster of unprecedented proportions” that “exposed the city’s vulnerability to the very waters that once made the port so successful.” New York’s history is thus brought full circle.

In another room you can watch this span of history unfurl in moving images, while a third gallery space, a “future city lab,” is dedicated to the dreams, visions, and proposals of both planners and exhibition visitors: what should and could New York look like up until 2050, encompassing housing, commerce, climate change, and transport. (I particularly liked “Paul’s” image of a self-driven buggy in Midtown, with the human inside happily snoozing as his vehicle did all the work. Then I thought, with alarm, how chaotic the roads are already.)

The museum has also supplied pencils and pieces of orange, blue, and green cards on which visitors are encouraged to write their hopes for the city, in completing the sentence “What if…”

Here’s a selection:

—“We loved others the way we love ourselves.”

—“Health care was free, preventative and guaranteed,” under which someone—presumably British—has added, “Then you would have the NHS.”

—“We all look at one another as equals, as our neighbors, as New Yorkers.”

—“There was no religion, no wars. We could all live in peace with each other. Wouldn’t that be nice?”

—“New York defies the anti-immigrant government of Trump, and continues to welcome new arrivals and capitalize on their ideas and energy.”

Reading the cards—the people’s optimism in the New York values so derided by the likes of Ted Cruz, their passion for this passionate city—you are reminded of the force and energy of all those who have helped shape the city in its 400-plus years of just-as-passionate history. So much has changed in New York, and yet—reassuringly—nothing has changed. As the exhibit shows, the city’s spirit is its most durable, seductive strength.

NY at Its Core is at the Museum of the City of New York, 1220 Fifth Avenue at 103rd Street. Book tickets, and more details here.