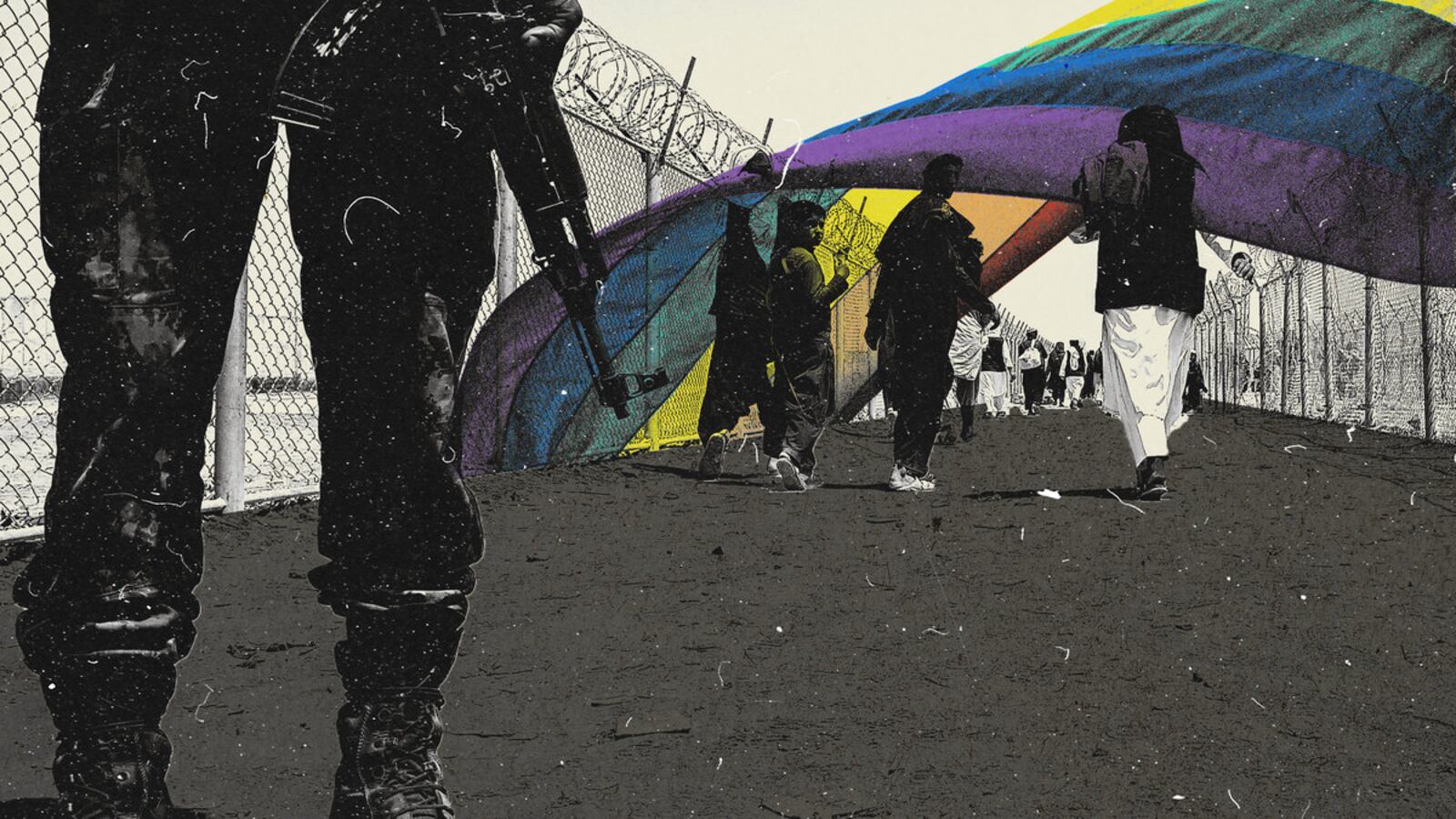

C says all he can see are tall buildings surrounding him. “It feels like I have escaped death, but now I am in a prison,” he told The Daily Beast through a translator. “I am in a boundary surrounded by four walls, not allowed to go anywhere.”

C is 26, gay, originally from Kabul, and has been in a refugee camp for two and a half months, having escaped Afghanistan in September in fear for his life. C asks The Daily Beast to not use his real name. His family is still in Afghanistan, and he worries about both their rejection and what the Taliban would do to them if his identity were known. He also asks us not to name the refugee camp, or its location, as he fears for his own life and safety within the camp should his sexuality be discovered.

C feels forgotten by America, and worried that he will be deported back to Afghanistan “where I fear I will be killed,” he told The Daily Beast. He is not alone. The advocacy organization Rainbow Railroad, which has been helping facilitate the escape and resettlement of queer Afghans, estimates there may be “hundreds” like him—LGBTQ people who managed to escape the country, but who have not yet made it to the U.S., the UK or other Western countries, and are instead in refugee camps in countries hostile to LGBTQ rights and people.

Jill Kelley, a former honorary ambassador to U.S. Central Command who helped evacuate hundreds—including C—during the chaotic dash to leave the country when the Taliban assumed control of it, says the State Department has “behaved terribly” towards C, and other LGBTQ Afghans like him.

“He is an innocent LGBTQ activist. This is what humanitarian efforts are made for,” Kelley told The Daily Beast. “If he is ultimately sent back to Afghanistan, our government has failed us horribly. It is terrifying and shaming. LGBTQ rights are a key part of the Biden administration’s platform, and it’s time for them to put their money where their mouth is. We are supposed to set an example to the world around human rights. The lens of our values and our democracy will be shown by whatever this young man’s fate is.”

Mark Pfeifle, deputy assistant to the president and deputy national security adviser for strategic communications and global outreach at the White House from 2007 to 2009, also helped in C’s evacuation. He told The Daily Beast that the United States “must bring people here whose lives will be destroyed if they are sent back to Afghanistan. They should be brought to a place where they can live and have a future.”

The U.S. State Department did not respond to repeated requests for comment on C’s specific case, and why he was still in the camp he is in—or what it was doing for LGBTQ Afghans in refugee camps in anti-LGBTQ countries.

Instead, it asked The Daily Beast to delay publishing this story until after its announcement of a Special Envoy for Afghan Women, Girls and At-Risk populations on Thursday. This person, an official indicated, would be focused on issues facing LGBTQ Afghans. The official also sent a detailed list of the various ways refugees can apply to enter America.

Kelley and Pfeifle insist they have passed on C’s details to officials, and tried to raise his case numerous times to no avail. The Daily Beast—with C’s consent—has offered to pass his details to the State Department, but no official has, at the time of writing, been in touch to take them.

Kimahli Powell, executive director of Rainbow Railroad, told The Daily Beast that in the chaos and desperation of late August many Afghans, including LGBTQ people, rushed to get out of the country any way they could, sometimes without knowing which countries they were going to.

The organization, Powell said, had only facilitated travel to countries where LGBTQ Afghans’ safety could be guaranteed, “because we were concerned about LGBTQ people being put in neighboring countries which were still hostile to LGBTQ persons.” Many thousands of displaced Afghans in the region are awaiting resettlement, including LGBTQ people, Powell said. The organization had received 900 requests for help in total, and Powell estimated that hundreds of LGBTQ Afghans were in a similar position to C in refugee camps in anti-LGBTQ countries, where they may be denied access to services, while fearing exposure, prejudice and violence from fellow campmates who may be homophobic and transphobic.

“They likely have a precarious status if they have any visa status, and the country criminalizes LGBTQ people or is hostile to them,” Powell said. “Most of these countries don’t want refugees in the first place. That’s when LGBTQ refugees’ safety becomes a concern, because with a precarious visa status they face deportation back to Afghanistan where they face almost certain punishment and potential death by the Taliban.”

Powell went on: “That’s why we want the U.S. government to figure out a pathway to get these people out immediately. The government has signaled to us that they are very aware of people like the man you are reporting on. We would just like to see them move faster to help them. We want them to work with civil society organizations on the ground, so we can identify and immediately relocate people like the man you have identified. If you are on your own without advocacy, that’s how you get lost.”

“All my hopes were washed away. There was nothing.”

C, a student and social activist, knows the violence of the Taliban all too well. “They killed my father, who was a police officer. They burned his whole body. I am very scared, I do not want to endanger my family. They are in danger right now because of me, and because of my father.”

He first realized he was gay when he was young. “It was very hard for me. I did not accept it, because I was not fully aware of being gay.” When he did accept himself around three years ago, he says he was relieved.

His family does not know that C is gay. “LGBTQ people are not accepted in Afghanistan, and my family would feel ashamed,” he says. His mother died 16 years ago, and he says he was afraid to come out “because I was worried I would lose my family, and they would kick me out, which I did not want after the death of my father.” He is also the family’s only breadwinner, so he wants to begin working to financially support them as soon as he can.

Kimahli Powell attends the Gay Times Honours 2021 at Magazine London on Nov. 19, 2021 in London, England.

Karwai Tang/WireImage/GettyLife in the refugee camp is hard, and he is mentally suffering. “There are thousands of Afghans here, and if anyone finds out I will be harassed here,” C says. “I do not know any other LGBTQ people here. I am not in contact with any homosexuals. That’s why my mental state is not good. I have not been in contact with anyone for three months.” C also has a partner who he has not seen for a long time. “I miss him. I want him to be in my arms, but he is not. He is also coming to America, and one day I hope we will be reunited.”

“Since Afghanistan is a conservative society, people are not mature when it comes to these sorts of issues,” C says about growing up gay in the country. “It’s not a safe place for LGBTQ people, even before the Taliban captured the government, but at least then there was a chance of living. I was living. You could have parties at night, meet friends, enjoy life a bit. But I could not be open about who I am, people would tease me about it, and now if people knew they would probably kill me.”

“When the government collapsed and the Taliban took over the country, I felt, ‘I am dead.’ All my hopes were washed away. There was nothing. Now you cannot listen to music, or wear what you want. The Taliban said they were forgiving people. This is false. They are taking people away, and killing them. I feel very hopeless, and also disappointed at what is happening to my country right now.”

“The biggest fear people reach out to us about is being outed and having their identity exposed,” Powell said, both inside refugee camps and also within Afghanistan. Before the Taliban takeover, while conditions were “not great” for LGBTQ people in the country, said Powell, “at least there was some degree of community. Now that sense of security has been compromised.” The organization has heard stories of the Taliban searching homes, beating people up, and threatening to return. LGBTQ people facing such situations in the country are “usually in hiding or living under precarious circumstances, worried they can’t stay in one place for long,” said Powell. “The amount of displacement is huge right now.”

C said after the Taliban took control of the country he had been unable to sleep. “Every single moment and moment I was terrified that I would be executed. I was living a life of terror, escaping one place and then another place.”

Kelley, C said, had kept him safe for the following three weeks, co-ordinating safe house after safe house, and protection and guidance leading to his ultimate evacuation. He was at Kabul airport, hoping to get on a flight out of the country, the day of the suicide bomb blast that killed at least 183 people. “I was 20 meters away. I was not afraid. All I could think about was getting out of Afghanistan. I was ready to take any risks. I was worried about the people around me in the safe houses. Were they spies? But they were just people like me, with sad, sad stories about why they had to leave the country. We were all hoping for better lives. Jill’s support was amazing. She kept me going all the way through.”

C felt safe when, many weeks later, his plane to freedom was in the air. “It started taking off, then stopped. I felt terrible and worried, and thought, ‘Is someone coming to take me off? I’m a dead man.’ But it was a technical issue. We took off again, and 15 minutes later I was happy. At last I had made it. I started rejoicing.” C said he knew of four other LGBTQ people who had escaped Afghanistan—two are in the U.K., and two are in Pakistan awaiting resettlement in Canada or the U.K.

“I dream every night of being able to live openly as who I am.”

C said the future for LGBTQ people in Afghanistan was bleak. “They cannot live there. It is impossible to live there. You either have to forget about your feelings or accept you can’t live there. The Taliban does not believe that people of the same sex can have those feelings for each other. There is no possibility of changing this perception, and there is nothing else but their intention to just kill or get rid of LGBTQ people.”

He added: “If they come to know someone is LGBTQ, they will definitely kill them. It is very hard for people like me. You have to leave the country because there is no possibility to live there because of who you are. But this is the country where you were born, and you cannot live there because of what you are. The only option is not to live there. LGBTQ people in Afghanistan, and refugees like me, need the help of Western countries to help them get out of there.”

In October, Rainbow Railroad facilitated the safe passage of 29 LGBTQ Afghans to the U.K., and Powell said the group could help oversee similar relocation efforts. “We just need governments to come to the table. We will support these LGBTQ people as much as possible as we wait for the government to live up to its commitments and promise.”

Kelley told The Daily Beast she offered her help to evacuate C, because like other individuals to whom she offered the same assistance, “I feared he would suffer the most horrible, barbaric death if the Taliban found him.” They stayed in touch by text, including terrifying moments such as during a gunfight, or when C, in the trunk of a car, could hear the Taliban asking questions of the driver.

“I emailed our political leaders about this LGBTQ activist, and no one responded,” Kelley told The Daily Beast. “I thought, ‘How dare we let this happen? This is why I pay my tax dollars.’ If I didn’t help him, who would? It’s still just as bad. My lawyers are frustrated with the State Department, and how incompetent and unorganized they seem to be. I just hope the State Department lets him, and others, in eventually, so he can be free to be gay here. I am deathly afraid that he may be sent back to Afghanistan. We cannot let that happen.” Kelley said she had overseen a vetting of C herself when helping him escape, to ensure that he did not represent any kind of danger.

Pfeifle told The Daily Beast that he was also determined to help C. “I can only imagine what it must be like to be in the trunk of a car, scared for your life, your cellphone battery going down, hearing what is going on outside. The worry now is that Afghan withdrawal challenges have faded off into the sunset. Southern border issues have become the focus of everyone’s attention, and people like this man are getting lost in bureaucracy and forgotten about. I am extraordinarily worried about his and other LGBTQ refugees’ safety and well-being.”

“The people at the top of the U.S. government need to assign people to focus on this. It’s a fight against time. We invaded that country in 2001, we had an incredible number of friends and allies on the ground who helped us. Now we need to help them, and the groups who are most vulnerable under Taliban rule we need to bring to safe places where they can live and have a future. That is our duty. This man represents all that’s good, all that’s possible about our future, and it should be a priority of any administration—including the current one—to do everything it can to bring him to a place where he can live and prosper. Without that, I fear the worst.”

Of his own future, which he hopes is America, C says, “It’s difficult and hard. Nothing is known yet.” If he finally makes it to America, C wants to continue his studies in political science, continue his social activism through YouTube and other media, and then get “any job” until he can specialize in his chosen field of IT.

“I dream every night of being able to live openly as who I am, spending time with other LGBTQ people, sharing and living with them. I am living for it.” C told The Daily Beast. “Physically, I am good, but psychologically I want to be with someone. I haven’t spoken with anyone, or shared my feelings, with anyone for so long. I ache to be with my partner, a man I can love.”

Kelley said C was “very down. All I tell him is, ‘Don’t worry, we’re going to fix this. I am going to help you. You’ve got to stay strong. Keep fighting.’”

“I am very strong,” C told The Daily Beast. “I do not accept defeat at all.”