Within your own backyard lies adventure that will transport you to a place that feels miles from home. So leave your passport behind and start exploring The Nearest Faraway Place.

For those with more esoteric tastes than the reliable New York Public Library can offer under its grand arches, Manhattan has no shortage of bizarre literary collections. Tucked away in bookshelves of hidden libraries across New York City are ancient mysteries, masonic orders, lost magic tricks, and expedition notes that make Hogwarts’ Room of Requirement look stale.

THE EXPLORERS CLUB

In 1951, the Explorers Club had a crisis on its hands: it had promised members attending its annual dinner that they’d be able to sample the meat of a 250,000-year-old woolly mammoth. When the supplier came back empty-handed, a member displayed the tenacity that likely earned him his admittance: he launched an expedition to Alaska and returned with the extinct animal’s remains. The dinner went ahead as planned at the Roosevelt Hotel where guests paid $9 a head to sample the exotic dish.

Today, the tusk from this ancient beast hangs above a window in the Explorers Club’s Trophy Room.

Tracing the fate of that meat was a recent request processed by Lacey Flint, the club’s archivist and research curator. She relays this story in the top-floor research library of Manhattan’s Explorers Club, surrounded by boxes of photo slides taken by Teddy Roosevelt, personal files on Amelia Earhart, and books documenting camel trains and submarine voyages to every corner of the globe.

The wide townhouses and manicured street dividers of the Upper East Side offer a properly historic setting for the glamorous 111-year-old Explorers Club.

The club doesn’t hold back with first impressions: the ground floor members’ lounge features a table made from a hatch of ship docked in Pearl Harbor on that fateful day in December; a chair belonging to the last dowager empress of China; and a cabinet of relics from century-old polar expeditions.

Theodore Roosevelt is the most famous of the historic membership, but the others hold their own against the swashbuckling president. Official explorers have gone to the highest points and lowest points on Earth, made it first to the moon, and summited Mt. Everest uncountable times.

The building itself is a six-story cabinet of curiosities. The real Indiana Jones’ whip sits on a mantle below a peg-legged explorer who hammered off his own frostbitten toes; a four-tusked elephant found in the Belgian Congo is on display; and scattered through the floors is a 14,000-volume library, including 1,400 rare books.

The literary collection began in 1922, when, according to Flint, then-President James B. Ford surveyed the 50 books they had at the time and declared “We really need a wealthy gentleman’s library.”

“They wanted to create the premier collection of explorers works,” says Flint.

So they did. Today’s assortment includes the first-edition 24-volume description of Egypt made by Napoleon on his 1798 expedition (the Rosetta Stone was found on that trip). The rare book room includes a collection that survived 25 years in the arctic after being left by a disastrous stranded expedition. In the entry hall, a display case contains the newly donated remains of that ill-fated expedition. “The Smithsonian wanted them,” says Flint with sly smile.

In the taxidermy-stuffed trophy room, she pushes aside a display case of African relics. Behind it, blended with the wood paneling, is a small, sticky handle that she pulls open with a shoulder-thrusting yank. The tiny, hidden room behind the door wasn’t listed on any of the building’s blueprints, and didn’t originally even have a door knob—only a lock on the inside. Inside are cramped bookcases filled with leather-bound works. A wooden board of Persian swords is propped against one section, and the books’ subject matter spans the world, from “Stalking Big Game with a Camera” to “The Land of the Pigmies.”

Across the hall, behind a door marked “Research Collections,” sits a larger chunk of the club’s diverse collection. This is where Flint brings the researchers. She’s working to get the collection online, but it’s a daunting task. “A lot of my inventory is handwritten,” she says. “In terms of archives, it’s really romantic, but usability is hard.”

For now, they still sift through thin boxes stuffed with Teddy Roosevelt’s lantern slides showing off his 1909 family safari to Africa. File cabinets are filled with personal details of deceased members, from Charles Lindbergh to Dian Fossey (women were admitted in 1981) to Scientology’s founding father, L. Ron Hubbard. Both members and the public are allowed access to the library, but they have to make appointments with specific requests that Flint follows up with preliminary research. Last year, she processed around 500 inquiries.

“They’re all a little strange because members of the club are all a little strange,” she says. “I’ve never gotten the same research request twice.”

CONJURING ARTS RESEARCH CENTER

In a building indistinguishable from the midtown Manhattan mess of chintsy jewelery shops and fabric factories, a buzzer indicates the fifth-floor occupancy of the Expert Playing Card Company. This is the money-making partner to the world’s most magical literary collection: the Conjuring Arts Research Center. When the elevator opens onto the floor they share, the view does not disappoint: a life-sized vintage poster of “Baldwin the White Mahatma,” a be-turbanded man showered by skulls, greets visitors.

A narrow hallway leads into a dark, packed three-room library out of your film noir dreams. A young volunteer pecks away at a laptop amidst the floor-to-ceiling bookshelves. The section markings hint at a fantastical 18,000-book collection, with categories that range from “Conjuring Theory” to “Mentalism,” “Escapes” to “Cryptology.”

Jennifer Spota, the head librarian and archivist at Conjuring Arts, explains that the works can’t be sorted by the Dewey Decimal system because they would all fall under “Magic Tricks.”

The center was founded by a magician named William Kalush in 2003. He found a home for his growing personal collection in the same building on 30th and Broadway where he ran a produce company.

Now Conjuring Arts has magicians like David Blaine sitting on the board and runs initiatives like the Hocus Pocus Project, which sends performers to hospitals and juvenile detention centers.

It’s open to the public by appointment during research hours, and attracts academics, history buffs and magicians looking for information about certain tricks, techniques or legendary figures. The books can’t be removed from Conjuring Arts but there are two lending libraries housed in magic shops in the city.

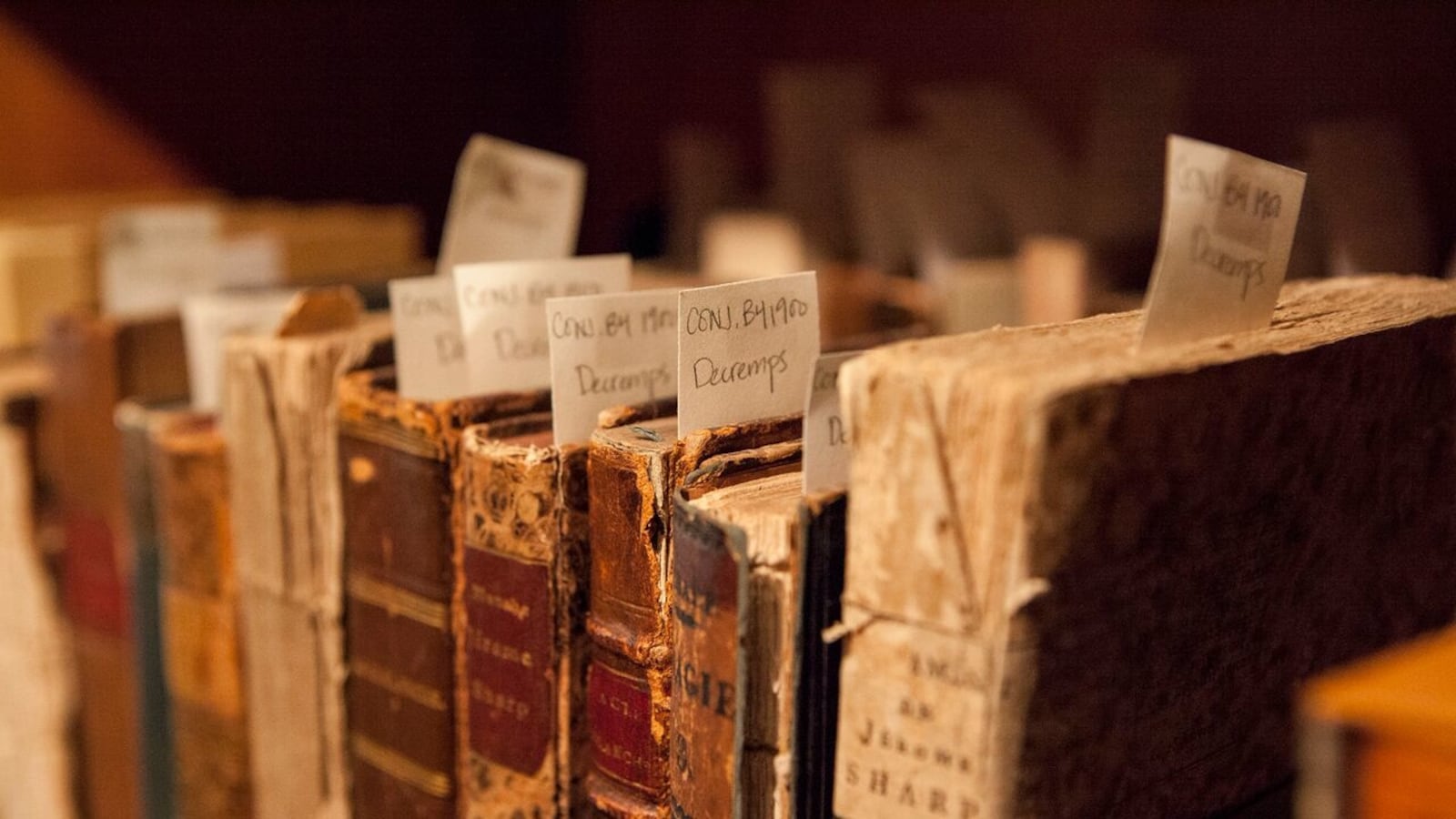

Abutting the library is the rare books collection, a small room covered in posters of the 19th and 20th centuries’ most famed magicians. A rectangular table occupies most of the room and the walls are stuffed with ancient texts of various origin, stretching back to 1481.

Spota will sometimes demand a trick as an entry fee. Navigating through teetering piles of books and letters in the maze-like back offices, she approaches Master in Residence David Roth, a renowned coin magician, who is translating typewritten correspondence that was recently scanned in by the digital librarian sitting nearby.

“Will you do a trick for us?” Spota asks.

“No,” he replies. “You can watch my videos on YouTube.”

Spota has no magic background other than a discovery of a Vaudeville performer in her family tree. But she’s fascinated by the look she gets into the private lives of the world’s most famous magicians. The center often receives letters, and she recently she scanned 5,000 pages of correspondence over 40 years between two magicians, Fawcett Ross and Ross Bertram. She came out the other side with a wealth of insight into the magicians’ community, but no party tricks.

“I can’t even shuffle a deck,” she jokes. “I clearly didn’t inherit Great Uncle Talley's skill.”

GRAND LODGE OF NEW YORK’S FREEMASONS

A few blocks south from Conjuring Arts, a waving flag on Sixth Avenue boasts familiar symbology: the square and compasses of the Grand Lodge of New York’s Freemasons.

For an organization constantly blamed for holding a secret power over global affairs, the Robert R. Livingston Masonic Library tucked away in the stately building offers unexpected transparency.

On a recent visit by an Atlas Obscura tour group, library director Thomas Savini satirically notes that the library chronicles the history of Freemasonry to “become the world-dominating order that it is today.” The group doesn’t laugh.

But it’s the fiction-fueled fascination with Masonry that has helped get a trickle of visitors through the glass doors of the Livingston library. “Some folks watched the History Channel and the Da Vinci Code and come in looking for a spaceship,” he says. They ask, “Do you really worship Satan?”

Savini has been a Mason for 23 years and served as the director of the century-old Livingston Masonic Library for over 15. He’s in charge of the 60,000 books, which are largely donated by the 70 different orders of New York lodges that use the building.

Eleven lodge rooms are open to the public in the historic building, but in an organization that keeps its inner workings locked tightly, few are aware of this library tucked away on the 14th floor. On a recent day, three visitors—one a member, another an inductee, the youngest a prospective—wander through the open room. An average of five visitors a day come see the collection, an estimated half from the general public and half from the 5 million of members worldwide.

The anti-Masonic visitors also “make frequent use of the collection,” Savini says. One drawer in the card catalogue spans from Ancient Mysteries to Anti-Masonic. “It’s not my business to change their mind,” he notes.

There are many misconceptions of Freemasonry that Savini would like cleared up by the texts he guards.

A door breaking up a wall of display cabinets in the back opens to the rare book room, and Savini takes out the 1793 manifesto of a German study group promoting social change, like the vote and religious freedom. This book, Spartacus and Philo and the Illuminati Order, would give birth to the idea of an enigmatic society that’s fueled centuries of conspiracy theories and Masonic lore. “The idea of the Illuminati or a hidden group of social change fomenting in the shadows really engrained itself,” says Savini.

Membership has been sliding over the past half-century, and the Mason style of not overtly recruiting members has hurt. There’s a “perception we’re a bunch of old men, which I think is inaccurate, but it’s an obstacle in appeal that we have,” says Savini. The last in a long line of Freemason presidents was Gerald Ford in 1977.

“We’re in an aggressive development phase,” Savini says of the library, which is going through a push to digitize. Earlier in the day, he had fulfilled a request to find material on 1700s New York lodge membership. Fifteen years ago, when he started, he would have slipped on gloves and made sure no one was around to disturb the delicate materials. “Today I did it with a click,” he says without nostalgia.

Savini hopes an online version of his carefully curated library will dispel some of the more rampant anti-Mason theories. The contents of the bookshelves are, he claims, “not the legend, not the myth, it’s the real facts.”