It took less than 48 hours for President Donald Trump’s euphoria over assassinating Iran’s premiere security official to become contempt at the Iranian refusal to accept defeat. Trump and his administration had insisted in the wake of killing Qassem Soleimani that they wanted an immediate “deescalation” of tensions. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, the administration’s premiere Iran hawk, has made that assurance to at least 10 foreign dignitaries, according to department call readouts.

But watching Iran opt against submission, Trump threatened not only Iran, but Iranian civilization. “As a WARNING,” Trump tweeted on Saturday, he had compiled a list of “52 sites,” payback for each of the hostages Iran took after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, “some at a very high level & important to Iran & the Iranian culture.” Those culturally resonant places “WILL BE HIT VERY FAST AND VERY HARD” should Iran attempt to avenge Soleimani. It was a declaration of intent to commit what is by definition a war crime.

It was also an expression of an impulse that has consumed America since 9/11 and that Trump has championed in its rawest form. Trump may declare his antipathy to endless wars, but the Soleimani assassination and its aftermath demonstrate why he hasn’t gotten around to ending them.

He and his allies instead reached in the aftermath of the Soleimani strike for the template established by President George W. Bush in the years immediately following 9/11, complete with unreliable narratives about intelligence, inflated threats, and maximally asserted authorities.

Vice President Mike Pence took the extraordinary Bush-era step of implying Iran was culpable in 9/11, something the 9/11 Commission specifically debunked. Robert O’Brien, Trump’s national security adviser, asserted that killing Soleimani was legal under the 2002 Authorization to Use Military Force, passed to give Bush the power to invade and topple Saddam Hussein’s regime. To complete the 2003 nostalgia trip, Fox News invited Bushies Karl Rove and Ari Fleischer, Iraq-war architect Paul Wolfowitz, and even Judith Miller, whose discredited WMD reporting for The New York Times intensified the Iraq war fever, to weigh in on Soleimani.

The deceitful, fearful politics of the war on terrorism are a central and underappreciated part of Trump’s rise to power. Those politics and their underlying logic fuel disproportionate violence, particularly against what they understand as civilizational insults, and rage against the institutional domestic voices that caution restraint.

Curdling as it ages, this kind of politics understands Iran’s clerical regime and its opposition to America in the Mideast as less a geopolitical adversary than a cultural insult stretching back even before 9/11, to the hostage crisis of 1979. That explains why Trump would respond to rocket attacks that killed a contractor with missile strikes in two countries, Iraq and Syria, and then respond to the subsequent assault on the U.S. embassy in Baghdad by killing the man in charge of Iran’s external security.

The hit had less to do with national security than it did with an aggrieved, hysterical sense of national honor. That’s also why Trump and his allies demonstrate little concern about its consequences, which are already destabilizing the U.S. position in the Mideast even before Iran launches violent retaliation. Their template, honed over a generation, glorifies retribution and seeks to cower dissent into acquiescence. It shows why Trump is no alternative to the war on terrorism, nor any departure from it. He is its inevitable product. As long as the war lasts, he is by no means its final form. And the war, left to its own devices, will last forever.

From the moment Trump killed Soleimani, legislators, reporters, and foreign-policy analysts asked what strategy the U.S. was now pursuing. Senate aides attending a Friday post-strike briefing came away frustrated at the lack of answers offered by administration emissaries. No strategy was on display–except for the obvious one, the last one left for a war in its 18th year: retribution.

The administration insists that it has a strategy, which it calls Maximum Pressure. Pompeo, unveiling that campaign in 2018, outlined its endpoint as some form of U.S.-Iran grand bargain–one Iran would have to enter after giving up its entire regional strategy after the U.S. gives up nothing.

Unsurprisingly, Iran has passed on that bargain, absorbing reimposed sanctions and U.S. bellicosity. Whatever pressure its government feels comes less from Washington than from its own citizens, who continue to suffer its violent repression. The administration’s response has been to declare Maximum Pressure a success while continuing to increase its posture of confrontation, a logic of escalation-to-nowhere that resulted in Soleimani’s killing.

Just as the Bush administration used moralism and deception to dismiss concerns about its unfolding war on terrorism, the Trump team has offered rapidly shifting rationales about the need to kill Soleimani. One of those rationales was eerily reminiscent of Bush deceitfully claiming Saddam Hussein posed an imminent threat to America, necessitating the 2003 invasion.

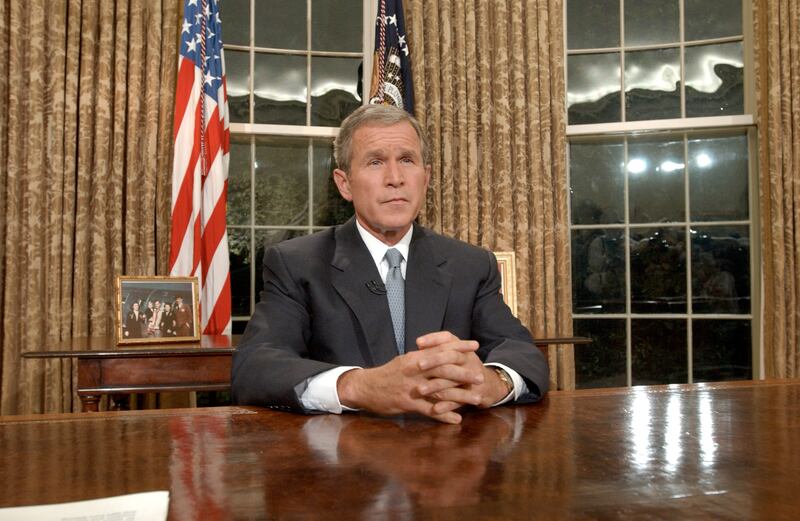

President George W. Bush addresses the nation from the White House following the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.

Greg Mathieson/Mai/GettyOn Friday, Pompeo said, specifically, that an “imminent” threat from Iran necessitated the strike–something that clashed with the Pentagon’s Thursday-night statement that Soleimani was only “actively developing plans” for some attack.

Attendees of the Senate briefing and those briefed on it who spoke with The Daily Beast did not hear anything that sounded imminent. Multiple reports over the weekend portrayed the threat intelligence about Soleimani’s fateful trip to Iraq as “business as usual” and Pompeo’s advocacy of killing Soleimani as months-old.

On Sunday, Margaret Brennan asked Pompeo on CBS’ Face the Nation if killing Soleimani actually ended the supposedly imminent threat. “There are constant threats,” the secretary rejoindered, as if that was exculpatory instead of damning.

Whatever Maximum Pressure has done, whatever killing Soleimani did, it has not stopped “constant threats.”

To Chuck Todd on NBC’s Meet the Press, Pompeo dismissed any violence that Iran will now launch against Americans–the entire rationale for killing Soleimani–as “a little noise here in the interim.” He completed his rhetorical move away from imminence in a Tuesday press conference that seemed to frame the killing not as preemption but retribution for the dead U.S. contractor.

“If you’re looking for imminence, you need look no further than the days that led up to the strike that was taken against Soleimani,” Pompeo said, before asserting vague “continuing efforts on behalf of this terrorist to build out a network of campaign activities that were going to lead, potentially, to the death of many more Americans.”

Nor could administration officials keep straight their versions of the scope of the allegedly imminent attack. Sometimes it threatened “dozens” of Americans, other times “hundreds” or even more. Pompeo on Sunday told Fox News’ Chris Wallace that Trump “didn’t say he’d go after a cultural site. Read what he said very closely.”

It took hours for Trump to lash out that it was only fair for him to respond to the history of Iranian roadside bombs in Iraq with cultural punishment. “We’re not allowed to touch their cultural site? It doesn’t work that way,” Trump insisted.

Anti-war activist demonstrate outside the Trump International Hotel in Washington, DC, on January 4, 2020.

Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/GettyThe absurdities compounded. Taking a hard pivot away from describing the intelligence agencies as a Deep State conspiracy to destroy Trump, Fox and Friends on Monday dismissed criticism of “our president’s decisions, our intelligence community’s decisions, our generals’ decisions,” since “everything [about the intelligence] can’t be made public.”

The more plausible reason Trump killed Soleimani is the one administration officials kept coming back to after being challenged on the intelligence and the strategy. It was one Bush adopted about Saddam to dismiss similar pre-invasion questions.

Soleimani was an evil man, Iran is an aggressive state, and America reserves for itself the right to kill people on that basis. The “terrorist” Soleimani–so designated by Trump, following in yet another post-9/11 tradition–”not only caused enormous death and destruction throughout the region, killed hundreds of Americans over the years, but had done so in the past couple of days, killed an American on December 27th,” Pompeo told Brennan.

In other words, America was settling a 40-year-old score. As Jeremy Scahill detailed for the Intercept, many on the right, from neoconservatives to nationalists, have never been comfortable with leaving Iran out of the war on terrorism. Many consider Bush’s 2002 characterization of Iran as part of an “Axis of Evil” a bold move that he unfortunately backed away from acting upon. They seethed as Iran faced no consequence for exploiting the Iraq occupation to kill and maim U.S. troops with powerful roadside bombs–something else that blurred the distinction between Iran and the war on terrorism.

The insistence on Soleimani as the incarnation of Iran’s evil has additional utility. It seeks to intimidate those who oppose the assassination and portray them as terrorist sympathizers, morally bankrupt, inauthentically American, and contemptuous of a suppressed people’s struggle for freedom. That worked exceptionally well for the Bush administration in the wake of 9/11. Democrats, sensing a vengeful national mood, opted for complicity or silence. Trump and his allies are running the play again.

“The only ones that are mourning the loss of Soleimani are our Democrat leadership and our Democrat presidential candidates” ex-U.N. ambassador Nikki Haley told Sean Hannity, who called Soleimani “evil.” On CNN, Bernie Sanders argued that U.S. assassinations of foreign officials will be useful for tyrants like Vladimir Putin, who see their value against domestic critics. “Bernie just compared @realDonaldTrump taking out a terrorist responsible for killing hundreds of thousands (including hundreds of Americans) to Putin assassinating his political dissidents,” tweeted a Republican National Committee communications director.

Some of the Democrats most complicit in the Iraq War, like Joe Biden, quickly reverted to type. Biden issued a statement saying Soleimani “deserved to be brought to justice” before retreating into the sorts of process concerns familiar from post-9/11 Democratic reluctance to oppose Bush. (“[Trump] owes the American people an explanation of the strategy and plan to keep safe our troops and our embassy personnel…”)

It fell to Sanders and the resurgent left–legislators like Ro Khanna, Ilhan Omar, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez–to reject unequivocally any war with Iran in terms as strident as those who advocate one. Often explicitly citing the Iraq War, they presented a tacit case, absent for a generation, that progressivism cannot coexist with endless war.

Liberals who consider Trump a departure from American traditions have hoped since 2017 that the military, the diplomats, the intelligence chiefs, and other security chiefs would stop Trump. But they–the people and institutions who built the war on terrorism and for whom hostility to Iran is often borne from direct experience–have been a minimal, reluctant bulwark.

Many in uniform consider Iran owes the U.S. a debt of blood for its role in amplifying the horror of the Iraq occupation. The Times reported that the generals actually presented killing Soleimani as an option for Trump. It was the sort of thing their experience with Bush and Obama during the Iraq and Afghanistan surges taught them would be rejected by commanders-in-chief who don’t wish to appear so extreme. But even after Trump took the option, a luminary of the war on terrorism defended it.

David Petraeus, his statements characteristically caveated, called the assassination “a very significant effort to reestablish deterrence, which obviously had not been shored up by the relatively insignificant responses up until now.”

Yet it cratered what remained of U.S. strategy in Iraq. Caretaker Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi, whom the U.S. outmaneuvered Soleimani to install, called for the end of the U.S. troop presence. Parliament voted on Sunday to expel the U.S., although a final decision may await Abdul-Mahdi’s successor. The U.S. military command in Baghdad announced it has suspended operations against the so-called Islamic State, even though the Pentagon deployed a fresh brigade to Kuwait, and is no longer mentoring the Iraqi military.

Whatever ultimately happens with the call for withdrawal–something which Abdul-Mahdi tempered on Monday–Trump’s first response was to threaten America’s nominal ally Iraq. He warned that he would sanction Baghdad, something that conjured the devastating human consequences of the '90s era sanctions, “like they’ve never seen before” and demanded reimbursement from a state the U.S. attempted at agonizing cost to secure as its major Arab client.

But Iran, and primarily Soleimani, outplayed the U.S. in Iraq repeatedly, something the past three presidents have refused to accept as the inevitability it always was. Iran is next door, and is now more unified that at any time in recent memory. Popular protests against the regime have given way to the massive national funeral processions for Soleimani, strengthening the hand of Iran’s maximalists. It turns out other countries also have nationalists who thrive off attacks from hostile foreigners.

Hundreds of protestors gathered during the anti-war with Iran rally at Times Square Saturday January 4, 2020 in New York, NY.

NurPhoto/GettyFor an exhausted, frustrated America, strategy is beside the point, as it only entangles the U.S. in a Mideast morass. What Trump seeks instead is zipless, frictionless violence. As he put it in a Sunday tweet, the response to any Iranian reprisal will be another U.S. attack, “perhaps in a disproportionate manner.” That impulse is the inevitable result of the catastrophe of the war on terrorism, where for 18 years raids and decapitation strikes have substituted for victory.

Trump’s threat against Iranian cultural heritage reflected the subtext of the Forever War: a clash of Western Civilization against supposed Islamic Barbarism, against which anything is permissible.

That subtext has never been respectable among the politicians, generals, intelligence chiefs, diplomats, lawyers, and other institutional figures that created and maintained the war on terrorism. Some deny that subtext even exists, preferring to consider declarations like Trump’s a vulgar, embarrassing deviation from an unfortunate geopolitical responsibility. But it has always been present, to varying degrees, in all their institutions, even at times prompting some of them to make efforts at eradicating it.

(It has been on relatively blatant display in American journalism, deliberately as well as tacitly, since immediately after 9/11, as when prominent conservative pundits lamented that the U.S. didn’t kill enough “Sunni men between the ages of 15 and 35” to forestall the Iraq insurgency.)

Whatever their intentions, the inability or reluctance of the political and security classes to resolve the Forever War guaranteed the viciousness would grow.

Being at war for so long has left a considerable number of Americans unable to reconcile their global dominance with the agony of being in a limbic state of neither peace nor victory. It has led a considerable number of them to consider brutality, which America can deliver, a substitute for victory, which America can’t.

In a post-draft America with minimal shared wartime sacrifice, few Americans actually wage the war on terror, meaning most of us experience it as a media event, the background noise from the TV or on social media, where its consequences are abstract but its frustrations intense. Such an experience is conducive to seeing an answer in “bombing the shit” out of people who live in “shithole countries”; to locking them up indefinitely with little or no legal redress; to surveillance scaled up to global levels and scaled down to Muslim-American civil-society leaders and even mosques; to torturing people in captivity; to hardening the border against the potentially dangerous, broadly defined, through the conflation of immigration with terrorism.

Versions of all of those practices have been justified, in sophisticated and eminently respectable ways, by Republican and Democratic leaders and the leadership of the security services.

Republicans, for a generation, have exploited this strain in American politics, while Democrats, more often than not, have cowered before it. Trump decided it was time that constituency had a champion–not someone who winked and nodded at it, let alone someone who condescended to it or called it racist. Trump understood the totemic force of defining an ever-elusive enemy through the deceitful, inflammatory phrase Radical Islamic/Islamist Terror, which means that terror is something Muslims, who are seen as subhuman, do and are. It is a moral judgment about who the architecture of state violence ought to be aimed at–and, inescapably, which Very Fine People ought to escape it. Failing to exercise maximum brutality on Muslim combatants and civilians alike is why, in Trump’s explanation, “We don’t win anymore.”

Trump expresses an antipathy for the war on terrorism that has confused elite observers, most infamously Maureen Dowd, who assessed him as “Donald The Dove.” Yet Trump’s stated antipathy has its limits. As president, he dramatically stepped up the aerial bombardment of Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan. However pointless Trump considers the Afghanistan war, he nearly doubled the troop commitment to it he inherited and cancelled peace talks with the Taliban in response to highly predictable Taliban violence.

In his first two years in office, Trump ramped up drone strikes beyond even what President Barack Obama, whose reputation is inextricable from drone warfare, did in his own first two years as president. He also removed restrictions placed by Obama that existed, however porously, to prevent unnecessary civilian death. When a CIA official showed Trump drone footage of a strike that killed a man after he walked away from his family’s house, the president misunderstood the message of precision the agency attempted to convey and asked, “Why did you wait?” To send his own message, he made a woman deeply implicated in torture the director of the CIA.

Trump possesses greater clarity about what the war on terrorism is than his journalistic or security-sector critics. His great political insight is to recognize that, for his supporters, the war on terrorism’s grotesque subtext of violence against nonwhites who are viewed as alien marauders is its emotional engine.

Contemptuous of their traditional elites’ inability to subdue a diffuse enemy, Trump and his allies, to the adulation of their political constituency, prefer to subdue those closer to home and easier to identify: Muslims, immigrants, nonwhites who expect America to fulfill its promises of equality and liberty, and the white progressives who claim to support the same objective. Trump correctly calls the car a lemon while revving its engine into the red. Doing so unlocks a panoply of authoritarian possibilities that stretch far beyond the war on terrorism, like separating migrant children from their families and locking them in cages. This is what it truly means to be exhausted by a war without end.

Whether Trump destroys Iran’s heritage or not, he reveals his understanding of victory: defilement, in cultural terms, of those who would frustrate him. Under Trump’s watch, the foreign battlefields of the war on terrorism have seen intensified bombings, raids, and other punitive measures. Even those who fought America’s wars for it can be abandoned to their violent fate once Trump sees them as encumbrances, just more subcontractors to stiff. With an embrace of brutality comes a delight in transgression, particularly when the typical lawyers or liberals or foreigners or Deep Staters howl objections. They walk into Trump’s trap: Aren’t these the people who got us into these stupid wars?

One of the things those people told them was not to start a war with Iran. For the Trumpists, though not only for them, Iran, the supposed architect of Radical Islamic Terror, has been at war with America since 1979, all while the U.S. refuses to fight back. This long cultural insult is inflamed by the insistence on restraint from the same political, diplomatic, intelligence, and military voices whom many allies of Trump view as enemies of the president. Cowing them into submission is as delectable for the nationalists as vaporizing Soleimani.

An important figure in the history of the war on terrorism exemplifies the intensifying grievances at its heart. When the planes hit the towers, Michael Scheuer was the chief of the CIA’s Osama bin Laden Unit, its leading al-Qaeda expert, and architect of its renditions program. Frustrated that his superiors and the Bush administration misdiagnosed al-Qaeda’s political agenda and were unwilling to pull the U.S. out of the Mideast, Scheuer–also a harsh critic of the Iraq war–published a book in 2004 arguing that “Islam is at war with America” and that the U.S. had no choice but to respond with far greater violence as a matter of survival.

After he left the agency, Scheuer’s trajectory followed America’s nationalist turn. He became a birther, a Trump supporter, and a devotee of the QAnon conspiracy theory. He recently mused about “loyal-citizen firing squads chosen by lottery” executing “Democratic coup-ists and insurrectionists” like Chuck Schumer, Nancy Pelosi, Adam Schiff, Barack Obama, his old CIA colleague John Brennan, and ex-intelligence chief James Clapper. After the Soleimani killing, Scheuer praised Trump for the kind of “non-intervention” and “America First” policy that the ex-CIA official believes is warranted.

“An Iranian military attack must prompt President Trump to unleash U.S. military power to destroy Iran’s oil-production facilities, or its navy, or its merchant fleet, or, better yet, all three. No U.S. troops on the ground, no occupation forces led by an imperial pro consul, no U.S. demands for changes in Iran’s government or its political and social systems, and no U.S.-taxpayer-funded reconstruction assistance. Simply let the Iranians lick their wounds, work out their post-catastrophe future, and reflect on the fact that, hereafter, it would be terribly unwise to again fuck with the Americans,” Scheuer wrote. He presented this as an alternative to the endless war, rather than its next phase.

But the war on terrorism isn’t only something that happens in Iranian oil fields, or in Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen, Somalia, Pakistan, and elsewhere on the map of violence. The war happens in America.

A women participates in demonstration against U.S. President Trump's travel ban as protesters gather outside the U.S. Supreme Court following a court issued immigration ruling June 26, 2018 in Washington, DC.

Mark Wilson/GettyThe war on terrorism is the Muslim-focused travel ban. It’s Trump’s demand that Muslim congresswomen Omar and Rashida Tlaib and two of their nonwhite colleagues go back where they came from. It’s the durability of mass surveillance, the refusal to admit refugees, the post-conviction detention of noncitizens, the militarization of law enforcement, the legal architecture that permits presidents to execute American citizens abroad without trial if an intelligence agency says capturing them is unfeasible, the enthusiasm not only for war crimes but for the men who commit them.

As long as all this and more remain entrenched in American political culture, the war on terrorism will survive any pullout from Iraq, Syria, or Afghanistan. It will produce more conflicts with countries like Iran. And it will produce more Donald Trumps.