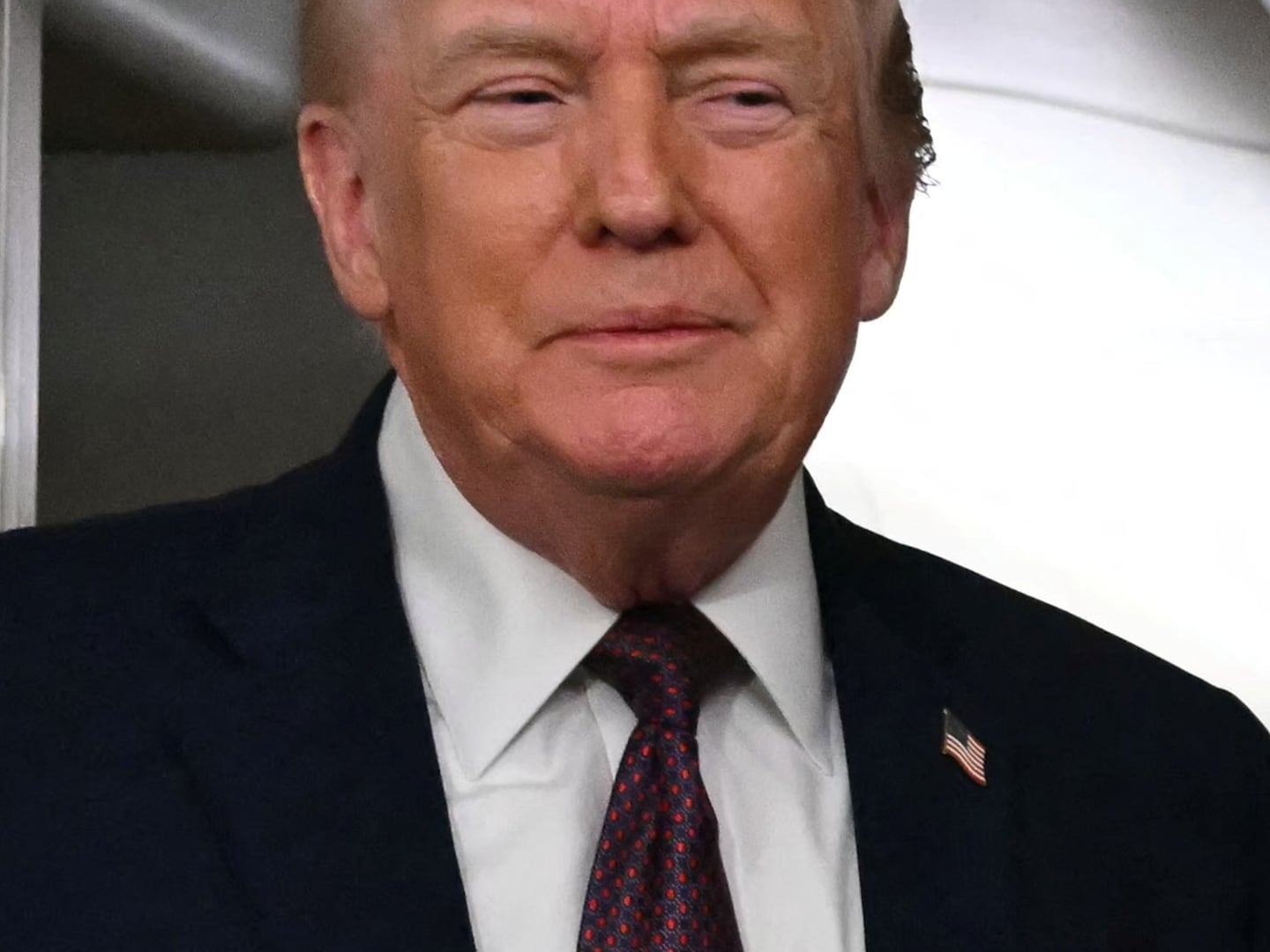

Former President Donald Trump has now been indicted for a fourth time, the most recent a 41-count indictment in Fulton County, Georgia, tied to his attempts to (in the words of the indictment’s introduction) “knowingly and willfully [join] a conspiracy to unlawfully change the outcome” of the 2020 election—a free and fair election that he lost.

The twice-impeached former president deserves due process, of course. He must have fair trials in each of the jurisdictions in which he is under indictment. But if he is convicted of any crime that would send an ordinary citizen to jail, he must serve time. That is true whether it is part of the mandatory minimum associated with the Georgia RICO statute, or the sentences that may be handed down in any of the other cases in which he is a defendant.

Just as hundreds of insurrectionists who answered his call to attack the Capitol are serving time, so should he be. Just as anyone else who stole national security documents from the federal government and then obstructed justice time and time again to hang on to them would be incarcerated for years, so should he be. Just as Michael Cohen or Reality Winner went to jail, so should former President Donald Trump. It is not enough for him to be found guilty and then to sit poolside at Mar-a-Lago wearing an ankle bracelet.

Last week, there was an essay in The New York Times by respected conservative legal scholar Jack Goldsmith, a professor at Harvard Law School, entitled, “The Prosecution of Trump May Have Terrible Consequences.”

It warns that “the costs to the legal and political system will be large” should Trump be convicted “before or after the election.” It offers a variety of arguments in support of its thesis—which is, in my view, dead wrong.

Goldsmith suggests that “even if” the Department of Justice is not driven by political motivations prosecution would be “unseemly.” He speaks of the “perceived unfairness” of the DoJ’s Russia investigation and of the “department’s treatment of Mr. Biden’s son Hunter.”

Never mind that there is absolutely no hint that partisanship has entered into the DoJ’s treatment of Trump during the Biden years. Indeed, quite the contrary, if anything, the Merrick Garland-led Justice Department has bent over backwards to avoid any hint of bias—including, notably, appointing an independent special counsel to oversee the Mar-a-Lago, Jan. 6, election fraud cases and, more recently, the Hunter Biden case.

Never mind that the Russia investigation conducted by Robert Mueller not only found substantial evidence of Russian assistance to Trump’s reelection effort and serial instances of obstruction of justice, but that those findings were unfairly minimized and effectively dismissed for political reasons by the Trump administration’s Attorney General Bill Barr.

Not only did Goldsmith not fairly address these issues, he goes further and says the facts don’t really matter. What matters to him is that the DoJ will be viewed post-prosecution as “an irretrievably politicized institution by a large chunk of the country.”

That a recent poll shows a majority of Americans believe Trump should have been charged with a crime in the Jan. 6 case goes unmentioned by Goldsmith. (An even larger majority approved of the New York indictment of Trump, according to an April poll.) That it would therefore be a minority who would be the ones politicizing the fair administration of justice does not appear to concern him.

He then goes on to say that the prosecution could damage the rule of law in the U.S., not because it is wrong or because it is actually political but because the unprincipled hyper-partisans might in the future use it as an excuse to drive “ever more aggressive tit-for-tat investigations” of future presidents. He argues also that trials like the special counsel’s Jan. 6 and election fraud case might contribute to the “criminalization of politics”—accepting the Trump defense’s argument that the former president was merely “being political,” not criminal.

Goldsmith also sidesteps Trump’s prosecution in New York by dismissing it as “dubious” and characterizes the federal cases as being led “by Mr. Trump’s political opponent.”

Interestingly, when raising the issue of Watergate, he suggests it is relevant because our experience since “deluded us into thinking independent council of various stripes could vindicate the rule of law and bring national closure in response to abuses by senior officials.” This is not only a dubious assertion, it is missing the far more relevant aspect of the aftermath of Watergate which is Gerald Ford’s disastrous decision to pardon Richard Nixon for his crimes.

That decision led directly to the presumption of many that presidents are above the law. It no doubt was factored into Trump’s perception of his own impunity should he run afoul of the law. One can only imagine how differently Trump might have behaved had Nixon actually been forced, as he should have been, to go on trial and do hard time if convicted.

Throughout our history, courts have been presented with circumstances when unpopular decisions might have alienated a segment of the populace. It runs against every foundational principle of justice to suggest that the size or volume of the mob’s protests should take precedence over evidence, due process, and ultimately justice. In a case like this, fearing an organized political backlash to Trump’s facing his just desserts is the type of politicization about which we should be most concerned.

Rather than being concerned about the impact on our system of letting justice be done, we must concern ourselves with the consequences of the miscarriage of justice that would result if Donald Trump could walk away from conviction for serious crimes with a slap on the wrist or no real meaningful punishment at all.

We already know that because Trump is a rich man (and because he has many supporters willing to help foot his massive legal bills) that he will use an army of lawyers and every legal tactic in the book to delay his trials, to disrupt them, to impede them and to appeal them. Surely, on some level he feels he can (as he has throughout his life) avoid responsibility for his actions simply by retreating behind a wall of lawyers and dubious legal tactics.

Perhaps his plan involves delaying justice until he can take office again and, at least on the federal cases, pardon himself. Perhaps he thinks he can just draw these cases out until he dies or is too infirm to sentence.

But what then? What message does that send?

How will it be taken in conjunction with the Nixon pardon and the erroneous Department of Justice Office of Legal Counsel memo that suggests a sitting president cannot be charged with a crime?

Should we end up there, we will have essentially struck through the words “Equal Justice Under Law” that are carved into the pediment of the Supreme Court and confirmed what many believe based on the other imbalances of power and fairness within our system: That presidents are above the law. We will have also created a new defense, that anyone running for office can no longer be prosecuted because by definition the case will be political. We will also have created a defense for anyone ever convicted of any of the myriad crimes for which Trump might ultimately be convicted.

Further, the arguments currently being fielded by Trump’s defenders create other peril—should they be acknowledged by credible legal scholars as reasonable in the way Goldsmith has bought into some of the most specious of Trump’s defenses.

Can a Republican no longer be tried in a jurisdiction that has elected Democrats in the past? Must we assume that no attorney general or judge can ever be fair should they be involved in a case in which the defendant is from a different political party? Can defendants with large crowds of noisy supporters expect their cases to be dropped?

No. None of these are risks we can or should run.

Each of the many cases against Trump must be conducted on the merits. The evidence must be weighed. Appeals must be heard where the law requires it. And then, should Trump be found guilty of crimes that carry a jail sentence, it is essential to our future as a democracy, it is crucial to the rule of law in America, that he then serve the sentences his crimes warrant.