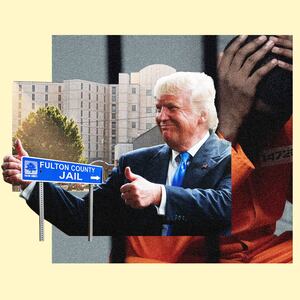

LaShawn Thompson shared something in common with former President Donald J. Trump. Both were defendants charged in Fulton County, Georgia, and booked at the Fulton County Jail—known as “Rice Street.” But that is their only shared commonality with the criminal justice system.

On Thursday, with TV cameras overhead and behind his motorcade following every moment of his journey, Trump arrived with an armed U.S. Secret Service escort, and sped through the process of paperwork and having his fingerprinting and mug shots taken like a VIP being let into a night club. It took only 24 or so minutes for him to be booked and leave the jail. His height was logged at 6-foot-3, his weight at 215 pounds, and his hair color as “blond or strawberry.”

The newly minted Inmate No. Po1135809 was back on his private jet within a matter of moments, after claiming again he had done “nothing wrong.”

But LaShawn Thompson never got to leave after his booking at Rice Street. He died there at the age of 35.

Thompson died at the Fulton County Jail after being held there for three months. According to his autopsy, contributing factors to his death included dehydration, malnutrition, untreated schizophrenia, and severe insect infestation on his body from lice and bed bugs.

His family’s attorney said he “was eaten alive by insects and bedbugs.” Thompson was charged with a misdemeanor.

By contrast, Trump is charged with racketeering crimes in a 41-count felony indictment and facing a total of four different criminal cases brought by prosecutors at the U.S. Department of Justice, Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, and now the Fulton County District Attorney’s Office. But the Fulton County case is the first time that Trump will experience the normal booking procedures of fingerprinting and likely be photographed for his “mug shot.” He also has release conditions that include bail.

Trump did not go through the same booking processes as other defendants in either of the two DOJ criminal and the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office. Nor did he have any bail or bond requirements in those cases. Perhaps the difference in Georgia is due to the fact that both the New York and federal systems were deferential to a defendant who once led the executive branch while Fani Willis feels no such obligation.

Or perhaps the difference is Trump is now a defendant facing a total of 91 criminal counts. But whatever the reasons behind Georgia’s decision, Trump and his supporters will continue to claim that he is the victim of political persecution and that there are “two systems of justice”—a supposedly lenient one for liberals and a supposedly harsh one for conservatives. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The real two systems of justice in our country is that the influential and wealthy experience one system while those with no influence and little wealth experience a wholly different one. Both systems can result in some measure of justice, either through a conviction for crimes or an acquittal, but in only one system—the one for those who lack influence and wealth—is the system itself a tool of punishment.

A police officer in Antioch, California, put it best in a text message about a suspect who suffered dog bites inflicted by police canines: “i (sic) feel like this is the real punishment compared to the soft DA” That’s not how it’s supposed to be.

The processing of a criminal defendant should be just that—a process—and that process should be a safe and humane one for every defendant who is innocent and not to be punished until they are proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. The process of being arrested and charged shouldn’t be viewed as comeuppance for anyone. The much talked-about “perp walk” is a great example of our society’s interest in punishment pre-conviction.

The act of parading a charged person for public humiliation dates back at least to the French monarchists paraded through the streets on the way to the guillotine and was updated—ironically—by now Trump co-defendant Rudy Giuliani, who liked to parade Wall Street defendants though a scrum of media that had been notified in advance by police when to assemble to provide maximum publicity for Giuliani’s career.

The popular practice of putting mug shots onto the internet—particularly those of celebrities—is another aspect of this pre-conviction punishment process. Recognition of the problems associated with disseminating mug shots—including promoting racial biases—have caused many news organizations to stop using mug shots as part of their stories.

But transparent processes like perp walks and mug shots may serve some kind of deterrent effect showing the public that even the rich and powerful may be brought to justice. In other instances, like the capture of a dangerous serial killers—for example the Son of Sam murderer in New York or the Night Stalker killer in Los Angeles—the visual of the perp walk and mug shot also serves to reassure the public of their safety. That is not true for dangerous and inhumane conditions in jails and prisons. Nor is it true for the abuses perpetrated by law enforcement.

Inhumane conditions in jails (whether for those awaiting trial or those serving sentences) and brutal treatment by law enforcement (including sexual assault and harassment) are not parts of the criminal justice system. Or at least they are not part of the sanctioned criminal justice system. In places like the Fulton County Jail, investigations by the DOJ and human rights groups using public records requests found “overcrowding, inmate deaths, excessive force from officers, structural issues, outbreaks of lice and scabies, and malnourishment among inmates.” And the Southern Center for Human Rights found in one 2022 outbreak that “100% of inmates in one unit suffered from lice, scabies or both” and 90 percent were malnourished.

The multiple cases now brought against Trump—and now, finally, those who worked with him to allegedly commit crimes—do show that our system is capable of holding even the powerful accountable. But they also shine a light on the horrors—and they are horrors—experienced at the hands of our criminal justice system by those not shielded by wealth, influence, and power. In the long run, long after the mug shots of Trump, Rudy, and others fade from memory, it is how we treat people like LaShawn Thompson that we as a society will be remembered for, and for which we should be judged.