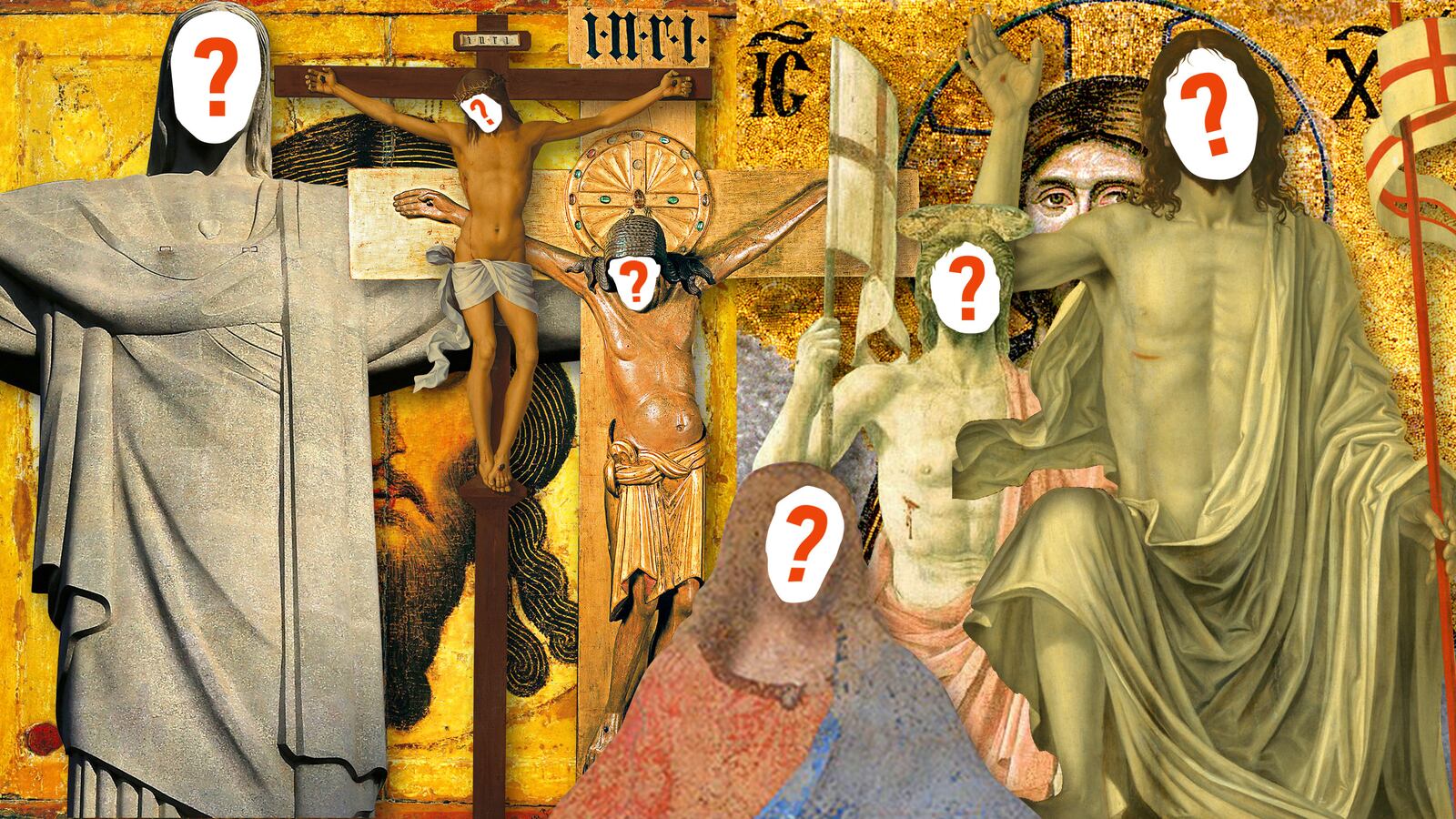

When Americans think of God, they tend to think of an old guy in a white robe and a long white beard. Our image of the patrician deity is painted by contemporary culture (think The Simpsons), though it has Biblical foundations. But when it comes to the appearance of Jesus, our mental portraits of the long-haired fella with the piercing blue eyes is very much the product of European and American artistic and cinematic imaginations. Now a new book by Professor Joan Taylor, of King’s College London, promises to answer the question: What Did Jesus Look Like?

To be sure, Taylor is hardly the first to ask and attempt to answer this question. It seems as if every few years a new study, analysis, or theory about the appearance of Jesus creates ripples in the media. Each study concludes in a similar fashion: Jesus was not the light-skinned, blued-eyed icon of Renaissance art, and he seems unlikely to have looked much like Willem Dafoe or Robert Powell. In recent years, forensic anthropologists have argued that Jesus was between 5’ 1” and 5’ 5” and weighed roughly 130-140 pounds.

Taylor’s scholarly best guess about the appearance of Jesus argues much the same: “Overall,” she concludes that Jesus was “probably around 166 cm (5 feet 5f inches) tall, somewhat slim and muscular, with olive-brown skin, dark brown to black hair, and brown eyes.” Her conclusions are drawn both from the skeletal remains of men buried in the region and from the close ties between residents of Judea and those who lived in Egypt. While conceding that there were ties between Judea, Europe, the Sudan and Ethiopia, Taylor argues that because Judeans tended to marry only among themselves, Jesus is more likely to have looked like the men depicted in Egyptian funerary art than a contemporary from Europe or Ethiopia.

Where Taylor goes further than her predecessors is in using clues about Jesus’ life found in the Gospel stories to deduce how Jesus’ social context and profession affected his looks. None of the writings of the New Testament explicitly describe what Jesus looked like. The most detailed description of his body is found in the “doubting Thomas” scene, in which Jesus refers to the marks of his crucifixion. We occasionally get references to his clothing, but this hardly helps us distinguish him from any other first-century resident of Galilee or Judea. The earliest artistic depictions of Jesus date to at least two centuries after his death. The second century Christian theologian Irenaeus tells us that other (to his mind, heretical) Christians claim to have a portrait of Jesus painted by Pontius Pilate. But there’s no evidence that such a thing ever existed; that Pilate was much of an artist; or that Pilate had time to make such a thing. There’s no first-century portrait buried in the desert and just waiting to be found.

This is where Taylor turns detective. Using the biblical descriptions of Jesus’ lifestyle, as an itinerant craftsman who spent a great deal of time walking but did not always have a consistent source of nourishment, she concludes that he was likely thin. But we shouldn’t leap to the conclusion (with many artists) that Jesus had a slight build. From the fact that Jesus was a carpenter Taylor observes that Jesus was a manual laborer engaged in physical activity and concludes that he was probably muscular and strong. The more effeminate depictions of Jesus as soft-limbed are out of keeping with the tasks he would have been expected to perform on a day-to-day basis.

Taylor actually thinks that the silence about Jesus’ looks says something about his appearance. She points out that certain Biblical figures, like Moses and David, were described in ancient literature in terms that gestured to their good looks and attractiveness. But the evangelists provide no such indications for Jesus. While his face is radiantly white at the Transfiguration (the moment in the story when Jesus goes up a mountain and converses with Moses and Elijah), we do not know anything else about his facial features. Taylor argues that the silence on the question of Jesus’ appearance suggests that, contrary to cinematic tradition, he was not handsome.

There are some difficulties with Taylor’s analysis: the Gospels were written decades after Jesus’ death by those who, in the majority of cases, had not met Jesus in person themselves. Even if they did describe Jesus’ appearance, how would we know if these descriptions were accurate? Moreover, we might dispute whether the marital and burial practices of Judeans and Egyptians provide good comparanda for assessing the height of an impoverished Galilean (Galilee is to the North of Judea and, thus, even further away from Egypt). But Taylor’s basic point that pale, blonde, blue-eyed Jesus is a projection of later European cultural values, though not entirely novel, is well made and robustly defended.

An interesting point made in the book is the question of whether or not Jesus was disfigured in any way. Noting that Jesus was a woodworker or craftsman, she points out that it is possible that Jesus had scars from his profession. As Christian Laes has shown in his recent edited volume Disabilities in Roman Antiquity, bodily disfigurement of one kind or another, though rarely considered in relation to Jesus, was almost the norm in the ancient world. Broken arms and legs would not have been set properly and would have caused limps and physical difficulties for the remainder of a person’s life; scars received in war, in childhood, or in domestic and professional accidents would rarely have been stitched. Those, like Jesus, who performed manual work were especially susceptible to hand and eye injuries. While blacksmiths wore eye patches to protect at least one eye while they worked, there was very little protective equipment available to the non-soldier and even less proficient medical care for the injured. It is highly plausible that Jesus, like other men of his professional class, would have been scarred or even lost full range of movement in a limb.

And yet few scholars think about the ways in which the historical Jesus might have been physically imperfect. Part of the reason for this is that Christianity in particular and society more broadly equate bodily perfection with bodily ability. For Christians this leads to the assumption that if Jesus had divine powers he surely would have been able to protect himself from injury or at least cure himself of any injuries he did sustain. Surely, the argument goes, an incarnate deity doesn’t trip and fall like normal human beings? The irony here is that Jesus does allow himself to be executed and permanently scarred on the cross (he still has those marks after his crucifixion). In other words, the argument doesn’t entirely make sense. It is rooted in popular prejudice. The idea that Jesus is able-bodied and physically unmarked is as anachronistic and prejudicial as the assumption that he had pale skin, blue eyes and blondish hair.