The image provokes both fear and fury: a wire coat hanger, spattered with blood, symbolizing the drastic measures women may take when abortion access is limited.

Whoopi Goldberg brandished one on stage at the 2004 March for Women’s Lives, urging the younger generation to remember what their forebears used. Protesters at the 1989 March for Women's Equality carried a giant replica, stained red, through the streets of Washington D.C. like a macabre parade float. And the symbol has been ubiquitous since Donald Trump’s election, popping up at marches, in the pages of glossy magazines, and on this site.

The imagery makes Jill Adams, founder of the Self-Induced Abortion Legal Team, shake her head.

“If I never see another coat hanger at a press conference again…” she said in a recent interview, trailing off wistfully.

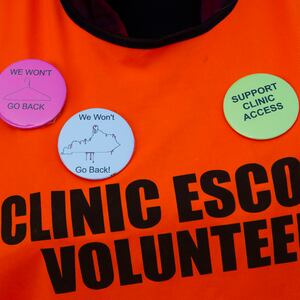

Adams is part of a new movement that advocates for a woman's right to perform her own abortion. The women refer to home abortion as “self-managed” or “self-induced”—the sinister-sounding “back alley” isn’t in their vocabulary—and argue that it is both safer and more accessible than ever before.

Non-clinical abortion isn’t something to be feared or shunned, they say: It’s just another choice under the “pro-choice” umbrella.

Ending a pregnancy without professional help has its risks, from medical complications to imprisonment. But the abortion methods available today—usually a combination of the drugs misoprostol and mifepristone—are much safer than those used before Roe v. Wade, when women resorted to drinking toxic chemicals or inserting objects like coat hangers into their uteruses.

Because of the safer procedures and a growing support network, advocates say, more women are seeing self-managed abortion as an empowered choice—not an act of desperation.

“In my experience, it isn't necessarily that people are reaching for that choice because they don’t have any other options,” said one member of the Knoxville Abortion Doula Collective. “It’s because it’s what they actively and autonomously want to do.”

Pro-Choice supporters take part in a March for Women's Equality in Washington, DC, 9th April 1989. They are carrying a huge representation of a bloody coat hanger.

Barbara Alper/GettyIt’s unclear how many women are actually choosing this option. Because half of American states either directly or indirectly criminalize self-induced abortion, most women who take this route don’t publicize it. But the growing interest in self-managed abortions is evident in the number of organizations springing up to support it.

This spring, the mail-order abortion pill service Women on Web opened its first arm in the United States. The company—which has quietly operated in countries where abortion is illegal for more than a decade—was recently inundated with requests from inside the U.S., founder Rebecca Gomperts told The Atlantic . In the first six months of operation, Gomperts said, she mailed abortion pills to some 600 U.S. women.

A year earlier, one of Gomperts’ former partners, Susan Yanow, launched an educational program called Self-managed Abortion; Safe and Supported (SASS,) which offers training on how to take the abortion pills safely, with minimal legal risk. The group has hosted more than 20 workshops and educated more than 300 people to date. Several doula collectives have also started offering information on the procedure, in addition to arranging funding and transportation for in-clinic abortions.

An even quieter network has also emerged to provide at-home abortions without the help of a doctor, according to multiple reports from this summer. The network deploys dozens of women, in every region of the country, using both medical and herbal methods. Adams’ organization, meanwhile, provides guidance to women who have ended their own pregnancies and are worried about legal repercussions.

Even some physicians, like obstetrician-gynecologist Jamila Perritt, say they now support women who decide to end pregnancies on their own.

“One of the things that’s always a priority to me, whether we’re talking about abortion care or reproductive health care in general, is that I trust the patients I take care of,” Perritt, a fellow with Physicians for Reproductive Health, told The Daily Beast.

“For some people, ending their own pregnancy in the privacy of their own home fits with the reality of their own lives.”

Women have been performing their own abortions for all of recorded history. Some scholars argue it is referenced in the Bible (God tells Moses to administer “bitter water” to women who become pregnant from “having sexual relations with a man other than your husband,”) and it appears in Persian medical texts as early as 865 A.D. Women in the Roman Empire ingested herbs to end their pregnancies, as did women in the early U.S. colonies.

The criminalization of abortion in some ways stemmed from a desire to wrest this control from women’s hands. The top proponents of an abortion ban in the mid-1800s were members of the American Medical Association who wanted, in part, to delegitimize midwives and concentrate medical power in the hands of physicians.

In 1859, physician Horatio Storer wrote that doctors were “the physical guardians of women and their offspring,” and that it was their duty to “govern the tribunals of justice” for all obstetric matters. The argument worked: by 1880, nearly all U.S. states had laws on the books criminalizing abortion.

Still, in the years before the Supreme Court ruled such abortion bans unconstitutional, women continued providing the service for themselves. In 1971, a California woman named Carol Downer organized her first class on abortion in a Venice Beach bookstore. The gathering spawned a movement, driving hundreds of women to explore their own bodies, administer their own self-exams, and in some cases, perform their own abortions.

At the same time, the women of the Jane Collective were administering up to 60 abortions a week in a Chicago apartment building. The collective started by referring women to doctors who would provide the service, but eventually decided to cut out the middleman and start performing abortions themselves. The women of Jane estimate they performed some 11,000 abortions in the early 1970s.

Women taking part in a demonstration in New York demanding safe legal abortions for all women.

Peter Keegan/GettyThen, in 1973, the Supreme Court decided Roe v. Wade. In a 7-2 majority, the court ruled that abortion access fell under a citizen’s constitutional right to privacy, but also that the “basic responsibility for it must rest with the physician.” As a result, women were directed to hospitals to end their pregnancies, and the practice of at-home abortions largely petered out.

Downer, 85, said she worries about the knowledge women lost over the ensuing years. While she obviously supports Roe v. Wade, she said it is important that women still take responsibility for their own reproductive health. Legislators and pharmaceutical companies, she said, “just want to make a society in which you never have to look at your own cervix, your own labia; you’ve been born ashamed of your very self.”

“A woman can go into a perfectly good, safe clinic and nevertheless come out of it feeling very isolated and ashamed,” she added. “I don’t think it’s a good idea to make [abortion] like any other procedure, because it isn’t.”

The current resurgence of at-home abortions comes in a political landscape increasingly hostile to abortion rights.

In 2018 alone, 13 states adopted 26 new restrictions on abortion and family planning, according to the Guttmacher Institute. The year before, nearly 50 abortion clinics across the country shut down, leaving 39 percent of reproductive-age women in counties with no abortion provider. The Trump administration has also allowed more employers to stop covering abortion in health insurance plans, leaving women to pay for it on their own.

Most news coverage of self-managed abortion focuses on this angle: the women being driven into it because they have no other option. A 2016 Glamour article on the “Rise of the DIY Abortion” quoted women who couldn’t find a doctor in their state, or who were afraid to disclose their pregnancies to an abusive partner. A feature in New York Magazine from early 2017 warned how “Abortion’s Deadly DIY Past Could Soon Become Its Future.”

But self-managed abortion advocates say that ignores the women who simply prefer to manage their abortions themselves—and can do so safely, thanks to recent medical advances.

In 2016, researchers at the University of Washington surveyed more than 20 women who had ended their own pregnancies. Most of them had already been through at least one clinical abortion before, and chose to self-induce out of a desire for privacy and control, or a better knowledge of their bodies. The decision to have an abortion at home was just that—a decision.

Katie, the volunteer for the Knoxville Abortion Doula Collective, can easily list off the reasons behind such a decision: undocumented women may be worried about being reported to authorities; trans men may feel uncomfortable in a clinic full of female-presenting people; others may simply prefer not to drive through a crowd of protesters. Still others may have been mistreated by gynecologists, obstetricians or other providers, and feel anxious in a clinic setting.

In Katie’s view, framing self-managed abortion as dangerous keeps these people from accessing the information they need to do it safely.

“It's the same sort of scaremongering that midwives see in reference to their practices,” she said. “People simply cannot imagine alternatives to the current medical system, even when it is shown to be incredibly dangerous— not to mention abusive—for most individuals to interact with.”

Adams, the founder of the SIA Legal Team, said the current conversation does more than just stigmatize home abortion. It helps criminalize it.

The FDA still tightly regulates abortion-inducing drugs, preventing them from being sold at retail pharmacies. For women who go outside this system—ordering from Women on Web, for instance, or using a physical method like menstrual extraction—the punishment can be severe.

According to the SIA Legal Team, seven states directly criminalize self-induced abortions. Ten states criminalize harm to fetuses without adequate exemptions for the pregnant person, and 15 have abortion laws that could be misapplied to women who self-induce.

In perhaps the most famous example of this, an Indiana woman named Purvi Patel was sentenced to 20 years in prison for allegedly inducing her own abortion in 2015. She served three years in jail before the Indiana Court of Appeals overturned her conviction, saying the state feticide statute was never meant to be applied to self-induced abortion.

By walking around with giant, bloodied coat hangers and writing think-pieces on the horrors of at-home abortion, Adams said, modern feminists inadvertently fuel the very people who would prosecute women like Patel.

“I know it can be difficult for some people to let go of powerful, arresting images and to update both their images and their rhetoric but it's necessary,” Adams said. “Because this outdated notion of non-clinical abortion being dangerous or unsafe, it contributes to stigma, and that contributes to criminalization.”

The controversial abortion pill known as RU-486, seen here as Mifeprex.

Getty ImagesThere are real concerns about a rise in DIY abortions, of course—not the least of which is safety.

The combination of misoprostol and mifepristone has been approved by both the FDA and the World Health Organization and is effective in ending pregnancies more than 95 percent of the time. It’s been used more than 3 million times in the least 18 years and resulted in 20 deaths, making it safer than both natural childbirth and common drugs like Viagra. Compared to the methods women used pre-Roe, said New York obstetrician-gynecologist Gila Leiter, it’s “like night and day.”

Still, Leiter counseled that taking the pills under a professional’s direction is always safer. Women who get their pills from a doctor’s office or clinic can guarantee it is the right medication and dosage, and that their pregnancy is intrauterine—a necessary condition of a medication abortion. A health professional can also ensure that the abortion has been completed and that there are no negative side effects.

“When it’s not regulated and you’re taking pills, there are always concerns,” Leiter said.

Others are concerned that safe at-home abortion methods, and the information needed to use them, are not available to everyone. Pills ordered from Women on Web, for example, are not covered by insurance, which could be a barrier for the 75 percent of abortion patients who are low-income.

Even Heather Booth, one of the founding members of the Jane Collective, was hesitant to endorse DIY abortion as a sustainable model. She commended the work that Jane did decades ago, and that places like Women on Web are doing now, calling it “brave and groundbreaking.” But she was skeptical that these services could provide the safe, supportive, and widely accessible care available at a well-supported clinic.

"Planned Parenthood, I know they have standards that I trust and value. I trust the leadership and I trust that that's the largest provider of health-care services for women in the country,” she said. “And I'm glad there are supplements to that, but I want to make sure that the main services for health care are not undermined, and right now they are being undermined.”

Booth’s comments reflect a quiet fear of some others in the pro-choice movement: that an increase in at-home abortions will impact clinics’ bottom line.

Many clinics already operate at a loss, charging rates that have remained stagnant for decades. Nearly 200 providers closed their doors or stopped performing abortions between 2011 and 2016, largely because of financial and logistical barriers, according to Bloomberg News. For the women who depend on these clinics for health care, that spells disaster.

Susan Yanow, who runs the SASS education program, said clinics are “caught between a rock and a hard place,” trying to balance their dedication to patient care with their need to stay afloat. There is a fear among some providers, she said, that a rise in self-managed abortions could mean a decrease in the number of people who come in.

But Yanow believes that many women have already self-managed their abortions for decades, and that the current conversation is simply bringing them to light.

“People think we are taking a piece of the pie by encouraging people to self-manage abortion,” she said. “I think the pie is bigger than anyone has known.”

Members of the self-managed abortion movement say this is exactly what they want—to be a piece of the reproductive choices pie. Adams describes her ideal model as “both/and:” Women can choose to go into a clinic if it makes them more comfortable, or take a medication at home if they prefer.

“We want everyone to have not just legal, but meaningful access to the full panoply of abortion care options,” she said, “which include provider-directed care and self-directed care; clinic-based care and home-based care, and other things we haven't even been able to imagine yet."

Major pro-choice groups also seem to be catching on to the idea. The Guttmacher Institute released a statement this year saying people should have access to a “full range of safe and effective options for abortion care”—including self-management with medication. The American Council of Gynecologists and Obstetricians declined to comment for this article, but has argued against criminalizing self-induced abortion in the past.

Katie compared current concerns about self-managed abortions to the outcry over the first home pregnancy test in the 1970s.

“Just as nobody bats an eye at the idea of a home pregnancy test now, we envision a society whose members are trusted to make pelvic health decisions autonomously, on their own terms—be it abortion, contraception, miscarriage management, or birth,” she said.

But first, we’d have to stop carrying around those damn coat hangers.