When people talk about the appearance of Jesus, the controversy is almost always about his skin tone and eye color. A whole tradition of Western artwork and moviemaking erroneously depicts the Galilean rabbi with light-colored eyes and skin, when archaeological evidence and, shucks, common sense maintain that he had much darker features. But what about the rest of his body? In particular, what about those body parts that mark him as male, which are so central to our understanding of who Jesus was?

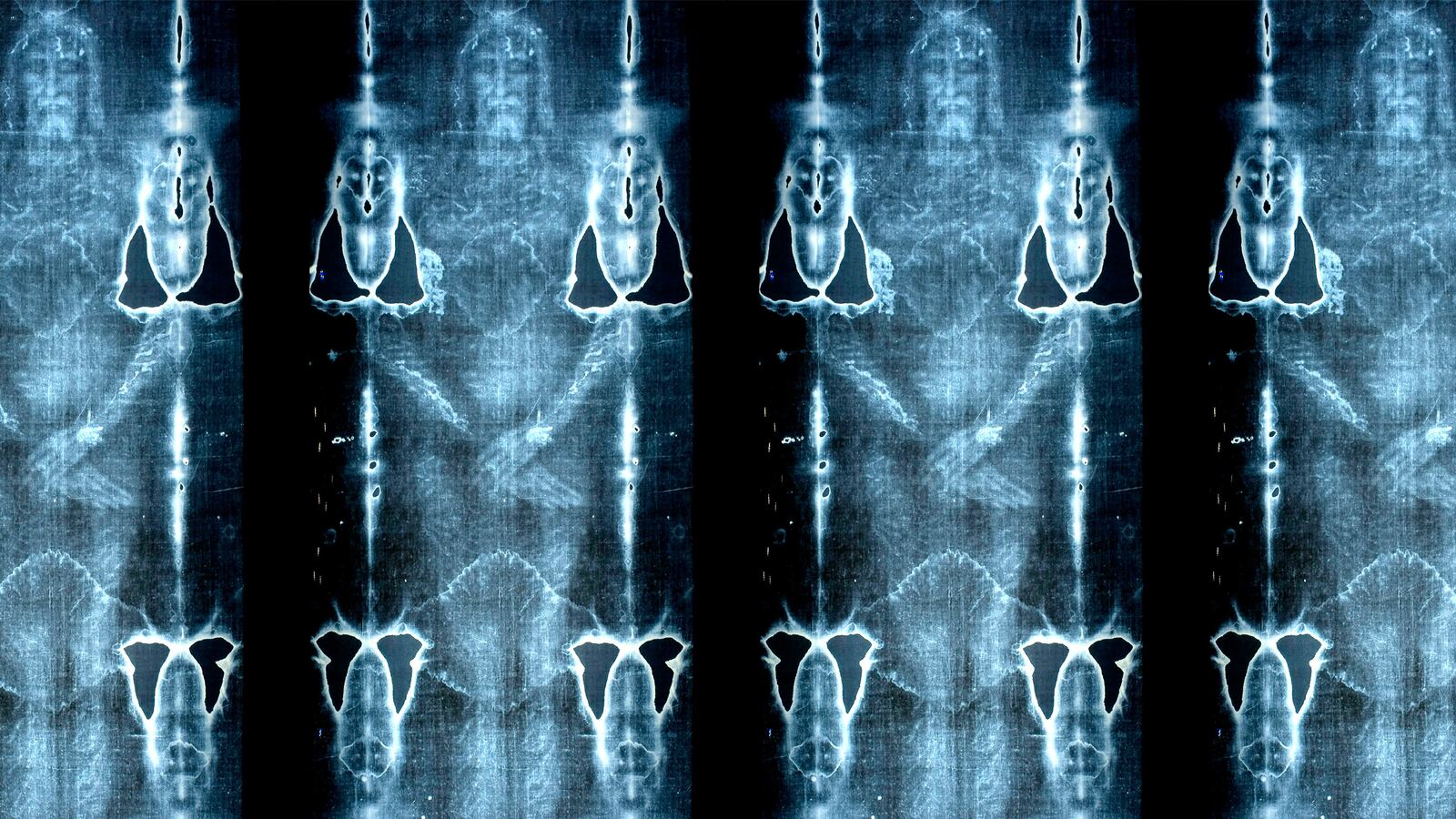

Newly published scientific investigations into the Turin Shroud have identified the outline of the scrotum and right hand thumb of the man outlined on the cloth. If the Shroud is authentic, this would seem to supply clear evidence that Jesus was, in fact, male. But a recent book by Giulio Fanti and Pierandrea Malfi aside, the majority of scholars believe that the Shroud is almost certainly a medieval forgery.

Which brings us back to the question: how do we know Jesus had male genitalia? To be sure, his behavior in the Gospels and the way that he is described by early Christian sources presuppose that he was male, but this does not necessarily tell us as much about his gender as we might think.

In 2014, Dr. Susannah Cornwall, who teaches at the University of Exeter, caused a stir when she published an academic article arguing that the sex of Jesus was simply a best guess. She wrote, “It is not possible to assert with any degree of certainty that Jesus was male as we now define maleness.” Correctly observing that it is difficult to speak definitively about the genitalia of an unmarried person with no children, she added, “There is no way of knowing for sure that Jesus did not have one of the intersex conditions which would give him a body which appeared externally to be unremarkably male, but which might nonetheless have had some ‘hidden’ female physical features.”

Her arguments prompted some fierce pushback, but should not be quickly dismissed. Dr. Cornwall is an established scholar and one of the global leaders in the theology of intersex. Her observations reveal a great deal about our own assumptions.

This isn’t low-stakes stuff: if Jesus was not male, then a number of arguments for the all-male priesthood of the Roman Catholic and Orthodox priesthoods are suddenly undercut. In fact, Cornwall’s article appeared at a moment when the Church of England was debating the legitimacy of female bishops. But, historically speaking, the genitalia of Jesus is about much more than the gender of Jesus: it is about his humanity.

A late fifth/early sixth-century mosaic in what is known as the Arian baptistery in Ravenna, Italy shows Jesus, naked in the river Jordan, with genitals clearly visible to the viewer. The rest of Jesus’ body is ambiguously gendered. He is depicted as clean-shaven, youthful, and even slightly wide-hipped. Some have argued that he is androgynous. Regardless of how we assess Jesus’ gender in this scene, the mosaic is pointing us to the idea that Jesus really was a human being, not merely appearing as one. The fact that we can see Jesus’ genitals (something that was unusual in Byzantine art) led to the baptistery’s name and association with the Arians. The Arians were Christians who held the now-heretical opinion that Jesus was not just a human being, but also a creature and, thus, not really and fully a god.

A more orthodox take on the significance of Jesus’ genitals for our understanding of who he was emerged in 15th- and 16th-century art. In The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and Modern Oblivion, Leo Steinberg noted that art of this period focused on the genitalia of both the baby Jesus and the dead Jesus. The point, according to Steinberg, was that genitalia represented the most sinful part of the human body. By focusing on them, Renaissance artists were highlighting that, in becoming incarnate, “God [joined] himself to the human condition to the point of sharing with man even that portion wherein retribution for Original Sin is most apparent.”

For some scholars, Steinberg was being highly selective. In her response, Caroline Walker Bynum, the Grand Dame of medieval history, observed that there are paintings like Quirizio of Murano’s The Saviour, in which Jesus is shown in the pose of a nursing mother. In other words, the imagination of this period was able to conceive of Jesus as either hypermasculine or deeply feminized.

However medieval and Renaissance artists might have imagined Jesus as a child or at his death, there were others who were focused on rediscovering the tangible reality of Jesus’ genitalia. The vast majority of Christian tradition maintains that Jesus ascended to heaven in bodily form. But there was a piece of him missing. As a Jewish male, Jesus was circumcised as an infant, an event referred to in Luke 2:21. Historians might imagine that his foreskin was simply discarded, but in the Middle Ages foreskin relics began appearing in Europe.

On Christmas Day in 800, Charlemagne presented one to Pope Leo III. He claimed that an angel gave it to him in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The Holy Prepuce (Holy Foreskin) was kept in the Lateran basilica before it was looted during the sack of Rome in 1557. According to David Farley, author of An Irreverent Curiosity: in Search of the Church’s Strangest Relic in Italy’s Oddest Town, there were at least eight, and perhaps as many as eighteen, holy foreskins in Europe during the Middle Ages. The most famous was the prepuce of Calcata (a town about 30 miles north of Rome), which was purported to be the foreskin stolen in 1557.

The debate over the authenticity of these relics infuriated the Vatican to the point that, Farley claims, in 1900 it was decreed that anyone who wrote or spoke about the Calcata prepuce faced excommunication.

An authentic foreskin relic would do a lot more than establish the sex of Jesus. If, in our twenty-first century, we had a piece of Jesus’ body, the problem would no longer be heretical claims about his gender or non-divinity, but rather the potential for sacrilege. If we had the DNA of God it would only be a matter of time before somebody wanted to clone him.