Of all the Founding Fathers, Thomas Jefferson is the one whose failure to apply the ideals of the Revolution to the institution of slavery is best known. His own writing left him fully exposed on the contradictions between his words and deeds. In the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson wrote that all men are created equal, and a decade later in his Notes on the State of Virginia he asserted that the relations between master and slave can only be “the most unremitting despotism on the one part and degrading submissions on the other.”

Despite these convictions, Jefferson did not cease being a slave owner, and as Annette Gordon-Reed established in her groundbreaking 1997 study, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, Jefferson had a long sexual relationship with the enslaved Sally Hemings in the years after his wife’s death. He fathered at least six children with her, four of whom survived into adulthood.

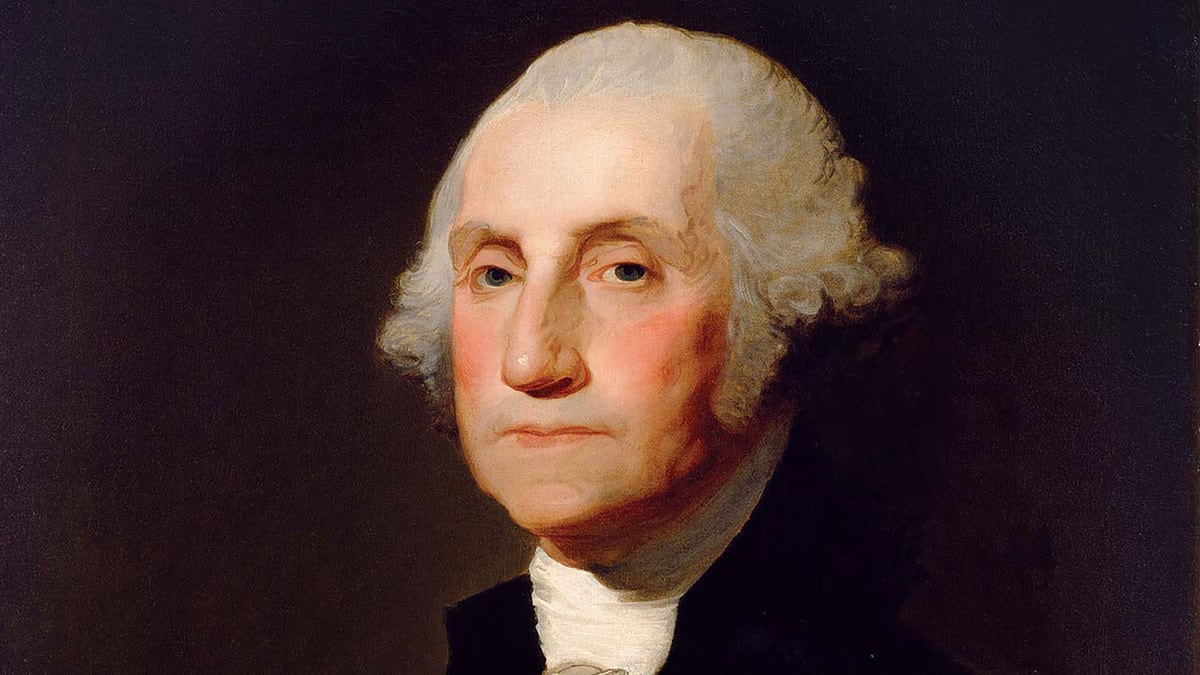

It is, however, George Washington who, as the first president of the United States and a Virginia slaveholder, had the greatest practical opportunity of any of the Founding Fathers to move the country to end slavery. By his example, Washington might have provided an answer to Samuel Johnson’s sardonic question, “How is it we hear the loudest yips for liberty among the drivers of Negroes?”

Instead, Washington played a cautious, often contradictory role with respect to slavery. Why he did so is the subject of a timely new book by Bruce A. Ragsdale, Washington at the Plow: The Founding Farmer and the Question of Slavery. Ragsdale, who has been a fellow at the Washington Library, Mount Vernon, has made extensive use of his familiarity with Washington’s life and letters.

The result is a portrait of Washington deeply rooted in the culture and politics of his era. Ragsdale notes that slavery was personally repugnant to Washington. He takes seriously Washington’s desire “to get quit of Negroes.” But he also emphasizes what is striking for us today: Washington never made a principled, public statement opposing slavery or offered a practical plan for ending it. Indeed, as late as 1775, Washington was still purchasing slaves.

On the eve of Washington’s return to Mount Vernon following the Revolutionary War, Lafayette, among others, urged him to free the slaves he owned as the culminating act of his leadership of the army. Washington did not take Lafayette’s advice, although in his private correspondence with the Philadelphia merchant Robert Morris, he made his antislavery views clear. “I can say that there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it,” Washington wrote, before going on to add, “but there is only one proper and effectual mode by which it can be accomplished, & that is by Legislative authority: and this as far as my suffrage will go, shall never be wanting.”

Cultivation of his vast landholdings by slave labor was, as Ragsdale notes, key to Washington’s success as a farmer. In addition, Washington found ways to train his slaves in other skills, from brick making to construction of the many buildings on his land. What Washington did not do was find ways to make the kind of scientific farming he admired succeed without the use of slaves.

Washington devoted himself to making Mount Vernon and the plantations he owned run efficiently. He was committed to the rotation of crops and the use of manure. He made sure his livestock and horses had the benefit of substantial barns and stables. And he stressed the use of ditching and hedging to mark off his fields and make them as fertile as possible. But when it came to his slaves, the best Washington could do was be a “good” slave owner and make sure his slaves had enough to eat and medical care. He was opposed to whipping and cruelty. But in place of such punishment, he stressed constant supervision of his slaves, not leniency.

Not until the end of his life when he concluded that most Virginia planters were unwilling to support any form of gradual abolition did Washington take a stance on slavery that came close to reflecting his sense of the injustice of it. In July 1799, five months before his death in December, Washington declared, “it is my Will & desire that all the Slaves which I hold in my own right shall receive their freedom.”

Nonetheless, even in his will, which was designed to free 124 persons at Mount Vernon alone, Washington remained the ever-cautious property owner. He specified that the actual freeing of his slaves should not occur until the death of his wife, Martha, and to this delayed emancipation he added one more clause. The freeing of the slaves should not take place until “after the Crops which may then be on the ground are harvested.”

It was Martha who in December 1800, a year after her husband’s death, freed Washington's slaves with a deed of manumission submitted in the Fairfax County court. Her actions reflected her desire to fulfill her husband’s wishes, but they were also done with mixed motives according to contemporary accounts. There was worry that, with the slaves’ freedom dependent on her death, Martha was in danger. As with so many other matters surrounding his slaves’ lives, Washington had not imagined how desperately they might view their own situation.

Had he foreseen slavery leading the nation into Civil War, would Washington have acted more swiftly to free his own slaves? It is not a question for which Washington at the Plow has an answer, but it is a question that reminds us that our racial past remains a volatile political issue for voters. Nothing makes that clearer than the Virginia governor’s race, where this month Republicans won an upset victory capitalizing on the false claim that with Democratic Party approval Virginia’s public schools are teaching a form of critical race theory that argues historical racism remains embedded in the state’s and country’s institutions.

Nicolaus Mills is professor of American literature at Sarah Lawrence College and author of Like a Holy Crusade: Mississippi 1964—The Turning of the Civil Rights Movement in America.