In the fall of 1988, shortly after Congress had passed the first piece of welfare reform legislation in 50 years, Joe Biden, then a senator from Delaware, wrote a column in his local newspaper that leaned heavily on racial stereotypes in praise of the effort.

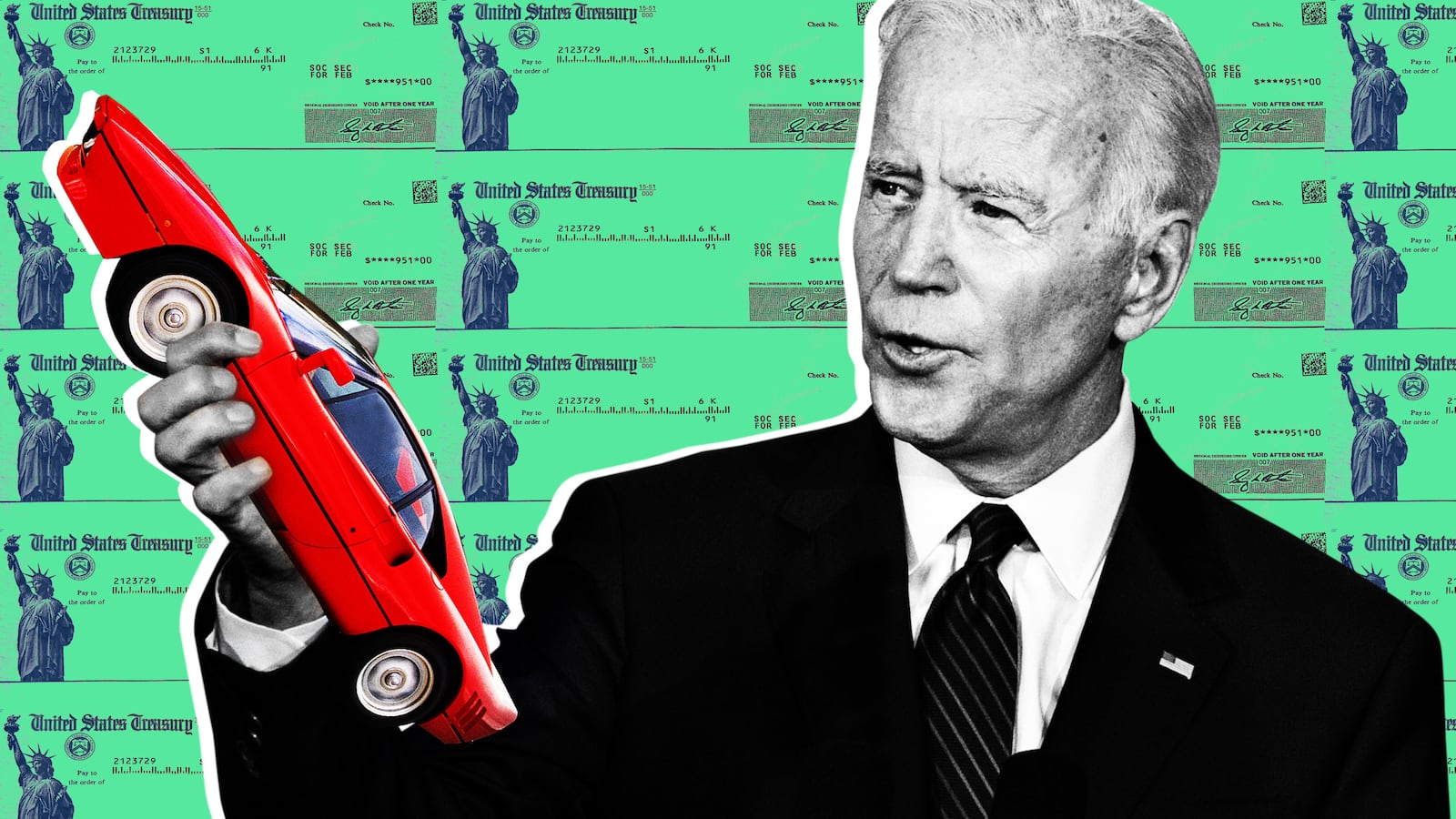

“We are all too familiar with the stories of welfare mothers driving luxury cars and leading lifestyles that mirror the rich and famous,” the column read. “Whether they are exaggerated or not, these stories underlie a broad social concern that the welfare system has broken down—that it only parcels out welfare checks and does nothing to help the poor find productive jobs.”

Biden’s argument, delivered in the pages of the Newark Post, was not a full embrace of the rhetoric of conservatives at the time, who warned that the indigent (in their estimation, mainly African-Americans) were using government assistance to supplement lavish lifestyles. But it certainly echoed it, adding to the perception that the problem wasn’t poverty itself but poor people abusing poverty-fighting programs.

“The thing that strikes me about the Biden quote is him acknowledging that it might not be true but then saying that doesn’t matter because perception becomes reality… that people’s attitudes need to be listened to and respected rather than corrected,” said Josh Levin, who wrote a book titled The Queen that traced the roots of the stereotype. Levin added that Biden’s line struck him as atypical of Democrats at the time.

Thirty years later, as Biden finds himself the frontrunner for the Democratic nomination for the presidency, both the column and Biden’s broader support for welfare reform could prove politically problematic—serving as another résumé spot, along with his prior praise for segregationist senators and his opposition to busing, that raises concerns about past cultural and racial insensitivities.

“It certainly was a racist narrative,” Adrianne Shropshire, executive director of BlackPAC and the affiliated nonpartisan Black Progressive Action Coalition, said of Biden’s use of the “welfare recipient with a luxury car” imagery. “That was obviously the sort of outrageous and untrue stereotype that emerged certainly during the era of Ronald Reagan, this notion of fraudulent undeserving women... I was a kid. And I remember that being the image—an image that, as a child, I knew was inaccurate.”

Noting that Biden had claimed in his column not to know if the stories were true, Shropshire added that it didn’t actually matter. “The challenge,” she said, “is when you lead with that image it actually negates in some ways what comes after it.”

For Biden’s campaign, the caveat in the column’s lead did make a difference, to the degree that it showed he remained doubtful about the welfare queen stereotype. But more important, they argued, was his broader history of opposing legislative efforts to fray the fabric of the social safety net.

“Throughout his career in public service, Joe Biden has fought for not just working and middle-class families, but also poor and struggling families,” said Jamal Brown, the Biden presidential campaign’s national press secretary. “As he wrote in 1988, we as a society have an obligation to help the less fortunate out of poverty through job training and educational and other opportunities.”

At the time that Biden was writing for the Newark Post, conservatives had made major political strides in arguing that the social safety net was being abused. Ronald Reagan in particular had warned of so-called welfare queens who not only were living off government handouts but living quite well. Such cases did exist. But they were often greatly exaggerated (indeed, statistics on such fraud shows that it is rare) or entirely misrepresented. As one 1984 Washington Post piece noted, it was a tax bill, not welfare, that was allowing “business mothers,” not welfare mothers, to purchase Mercedes.

Still, Democrats embraced reform, either convinced of its merits or spooked by the attacks. The legislation to which Biden was referring in his Nov. 3, 1988, article—which The Daily Beast unearthed through a larger review of his columns—was The Family Support Act. It enhanced child support collection, created job opportunities and training for families on welfare, and established that single parents with a child over the age of 3 must enroll in educational activities or vocational training in order to receive full government assistance, provided that they had child care services as well.

The bill was championed by Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-NY), a liberal stalwart, and was embraced across the political spectrum.

“Welfare policy should be based on a simple premise: we have an obligation to help society’s less fortunate receive the education, training and transitional services they need to work their way out of poverty,” Biden wrote. “In return we expect a commitment from them to do all they can to succeed in becoming productive members of their communities.”

But the 1988 law didn’t satisfy the reformers’ itch. And when Bill Clinton campaigned for the presidency in 1992 he did so, famously, on a plan to “end welfare as we know it.”

It would take years for that promise to come to fruition. But when it did, Clinton found an able ally in Biden.

In the mid-’90s, Biden continued to push for major reforms to the welfare system. He insisted that “too many welfare recipients spend far too long on welfare and do far too little in exchange for their benefits.” He argued that welfare recipients should have six months—“period”—to find a job in the private sector or give up their benefits. He said Congress should “require all welfare recipients to sign a contract in which they agree to work in exchange for their benefits.”

But he was hardly a conservative ideologue in pursuit of reform. He opposed a provision that would have prohibited additional cash assistance “for children born to families already receiving assistance.” And he supported an amendment that allowed states to use federal block grant money to provide non-cash assistance to children whose families had hit their welfare support limits.

In 1996, Congress passed welfare reform far more sweeping than the version they’d done just eight years prior. The legislation put a five-year lifetime limit on how much assistance could be given to any family and gave states much greater latitude on how the program was administered. It created more stringent work requirements, limited the ability of legal immigrants to get assistance, and put restrictions on food stamp eligibility.

“Compared to ’96, The Family Support Act was a relatively progressive bill,” said Elizabeth Lower-Basch, a senior policy analyst at CLASP, a national nonprofit organization that promotes policy solutions that work for low-income people. “’96 fundamentally restructured the core underlying program.”

Democrats were sharply divided on the measure. Clinton signed it after vetoing two earlier versions but even expressed his displeasure with the eventual compromise. “You can put wings on a pig,” he said, “but you don’t make it an eagle.” All told, 24 Senate Democrats voted for the bill and 23 opposed it. Liberals like Sens. Russ Feingold (D-WI) and Tom Harkin (D-IA) supported it. Moynihan was among the nays, warning that the bill would put children “to the sword.”

The legacy of the ’96 bill remains disputed to this day. In the years after passage, welfare rolls plummeted as single, never-married mothers entered the workforce. How much of that was due to the improving economy overall or the law specifically is debated, though academics do credit the legislation with boosting employment and reducing poverty by non-insignificant percentage points. But those gains did not come without pain elsewhere. As Jordan Weissmann noted in Slate:

<p>The Urban Institute’s Pamela Loprest and Sheila Zedlewski <a href="http://www.urban.org/research/publication/changing-role-welfare-lives-low-income-families-children/view/full_report">found</a> that during the early post reform era, about one-third of single parents were jobless soon after leaving welfare. Those who did find work often earned no more than what they lost in benefits; studies have concluded that anywhere <a href="http://www.nber.org/papers/w8983.pdf">from 42 to 74 percent of those</a> who exited the program remained poor. Meanwhile, states began enrolling fewer new families in welfare. As the rolls shrank, a new generation of so-called disconnected mothers emerged: single parents who weren’t working, in school, or receiving welfare to support themselves or their children. According to Loprest, the number of these women rose from 800,000 in 1996 to <a href="http://www.urban.org/research/publication/dynamics-being-disconnected-work-and-tanf">1.2 million</a> in 2008. </p>

Biden, as recently as 2012, defended the ’96 welfare reform, saying opposition to it at the time “made no sense.” But his spokesman Brown also noted that Biden has voted to maintain public assistance for children of immigrants and opposed efforts to cut food stamps. “As president,” Brown said, “Biden will continue fighting each and every day for Americans of all socioeconomic backgrounds.”

And even though he adopted traditional conservative rhetoric in the late ’80s, not everyone in Democratic politics feels it is worth dinging him on it.

“The question remains,” said former DNC chair Donna Brazile, “where is he now?”