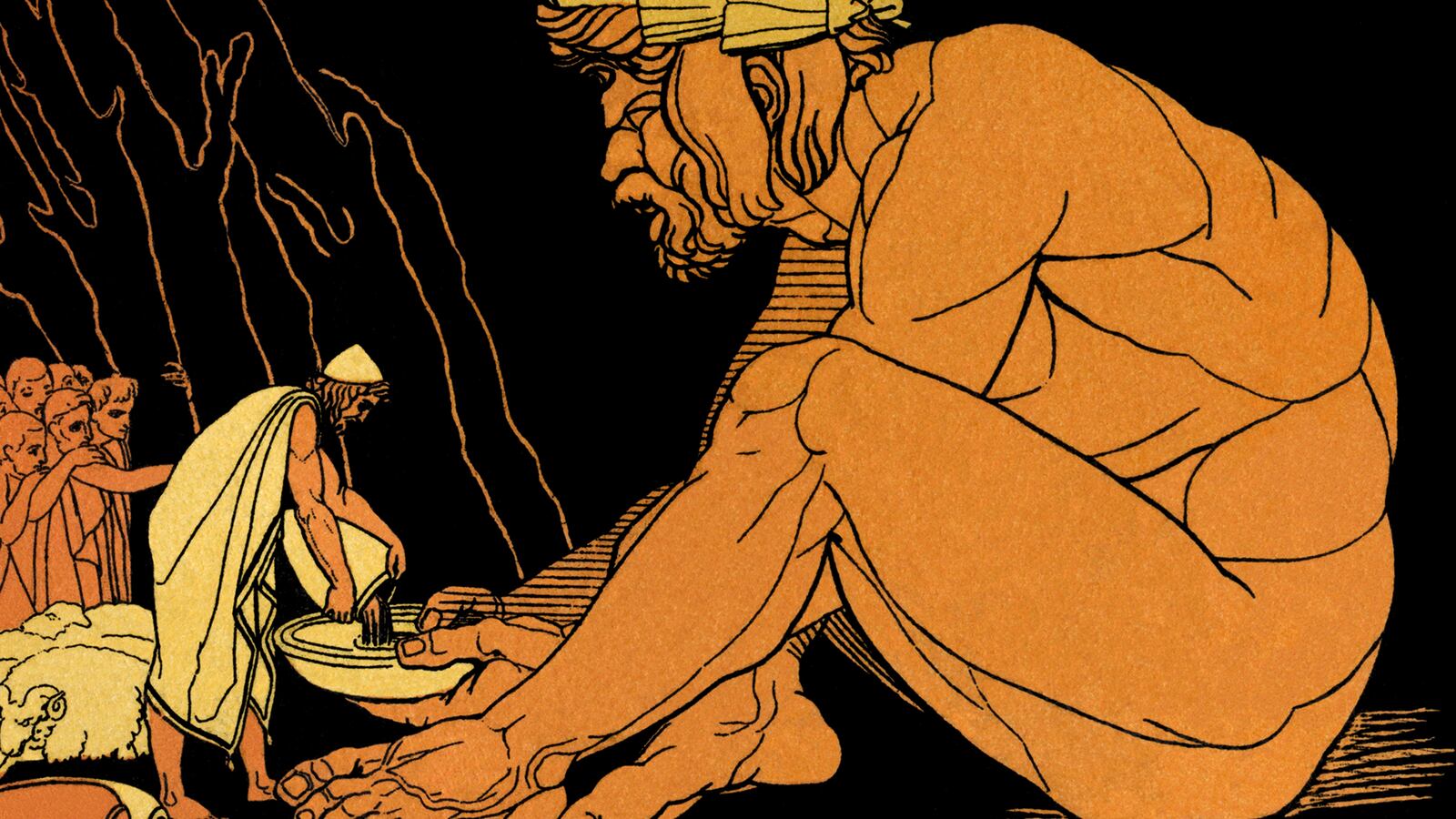

Wherever you go, people have their giants. The ancient Greeks had Atlas, the Titan who holds up the world, and Polyphemus, the cyclops who liked to eat people. Norse legend describes a Hrungnir, a belligerent drunk who boasted that he could kill the gods. Japanese folklore has the oni, fearsome former humans who favor the taste of mortal flesh. And J. K. Rowling has Hagrid, who has questionable taste in pets. Arguably the most famous of the giants, though, is Goliath the biblical antihero who, like most of mythology’s giants, is tricked or killed by an enterprising human being. But other than the mere fact of tall people, why are our old stories and myths teeming with giants? A new archaeological theory promises to explain the roots of the biblical idea.

As anyone who attended synagogue or Sunday school knows, Goliath of Gath was a 10th-century B.C. giant who served as the champion of the ancient Philistine army. He was killed by a small stone flung from the slingshot of the shepherd boy (and future king) David. David had stood in for Saul as the representative of the Israelite army. Goliath was killed and the Israelites were victorious.

Despite the best efforts of many to reconstruct the events behind this story, it is generally agreed that it has—at most—a kernel of truth at its core. So if there was no epic duel then where does the mythology of Goliath come from? A new article published in the Journal of Biblical Literature by Prof. Aren Maeir, director of the Tell es-Safi/Gath Archaeological Project, tries to unravel the mystery.

Maier’s archaeological project studies the distinctive architecture of Tell es-Safi or Gath, the traditional home of Goliath. The site was first settled sometime in the late prehistoric period around 5000 B.C. and was continuously inhabited for approximately 7000 years until the Arab Palestinian residents of the site were expelled during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. It lies midway between Jerusalem and Ashkelon and is one of five Philistine cities mentioned in the Bible.

What’s distinctive about Gath is its large-scale buildings. Maier told the The Daily Beast that “in various parts of the site, including the fortifications, various buildings and even offsite, we see relatively large amounts of large worked blocks of stone used in architecture.” The massively outsized architecture, Meier said, was “visible for centuries” even after the city was destroyed in the ninth century B.C. by King Hazael. The scale of the city, Meier said, “is somewhat different” from what we see at other sites in ancient Israel. Meier hypothesizes that those who saw and explored the ruins of Gath long after it had been destroyed might well have assumed that the ruined city once housed giants. It takes a great deal more effort to move large blocks of stone than small ones. Who else other than giants would have done such a thing? This assumption, in turn, “fostered the stories” about Goliath and other giants from Gath.

The idea that architectural style formed the basis for ancient theories about the physiology of a place’s occupants is not worlds away from the principles that inform modern archeological methods today. The same hypothesis has been used to explain the myths about Cyclopes among the ancient Greeks. It’s not a modern theory, either. The encyclopedist Pliny wrote in his Natural History that the Cyclopes were the inventors of masonry towers found in Greece and the term “Cyclopean masonry” continues to be used in modern archeology.

The mythology of giants, however, was ideologically important to later generations of ancient Israelites. Maier argues that in the later Iron Age, as Israelites worried about the military power of the Assyrian empire, the giants of the past were reconceived as the political giants of the present. The enormity of Assyrian power meant that Goliath was “keyed” to the new threat of Assyrian power. “Just that as the Assyrians were the main threat in the later Iron Age,” said Meier, “perhaps the image of fighting a giant (Goliath) was transferred to the image of fighting another giant (Assyria).”

Certainly, the description of foreign powers and their leaders as monsters occurs elsewhere in the Bible. The books of Daniel and Revelation both use the image of monsters to describe foreign rulers and powers. The same thing happens in American history. John Quincy Adams invoked the same idea of foreign monsters when he said, in a 1821 address, that America does not “go in search of monsters to destroy.” Adams’s statements are not a one-off; the practice of associating real foreign military threats with mythical or cultural monsters is a feature of propaganda. Those who colonized the new world in the 17th century spread rumors that the inhabitants of the North Atlantic were cannibals as a way of instilling fear and justifying abuse. Propaganda released on posters during World War I encouraged American men to enlist in the military by depicting the Kaiser as a mustached ape-like monster that threatened the U.S. The imagery in Harry Ryle Hopps’s Destroy This Mad Brute (1917), in which the Kaiser-ape abducts Lady Liberty, formed part of the inspiration for the 1933 film King Kong.

Were the giants of Gath the King Kongs of their day? Perhaps, but there are other biblical giants, like the watchers mentioned in Genesis 6:1-6 whose origins seem to lie in a more prosaic phenomenon: tall people. Given that hereditary traits are often local it seems plausible that at least some myths about giants were related to encounters with groups whose members were simply taller than average. In the case of Gath, however, the tall tales about giants might be founded on nothing more than architectural style.