It’s shortly after midnight on a still autumn night in 1961 over the forests of northern Rhodesia. Onlookers glance upwards to see two planes streak across the sky. One of them has fire lapping around its engine and wings and plummets to the ground.

Across the Mediterranean Sea, American NSA agents stationed in Europe intercept a congratulatory radio transmission. “The Americans just shot down a UN plane,” an accented voice says.

The next morning, civilians approach the wreck—some say they see a fuselage riddled with artillery and a man struggling for life. An investigator observing the bodies notes bullet wounds. The plane’s lone survivor stays alive just long enough to describe a series of explosions before the craft went down.

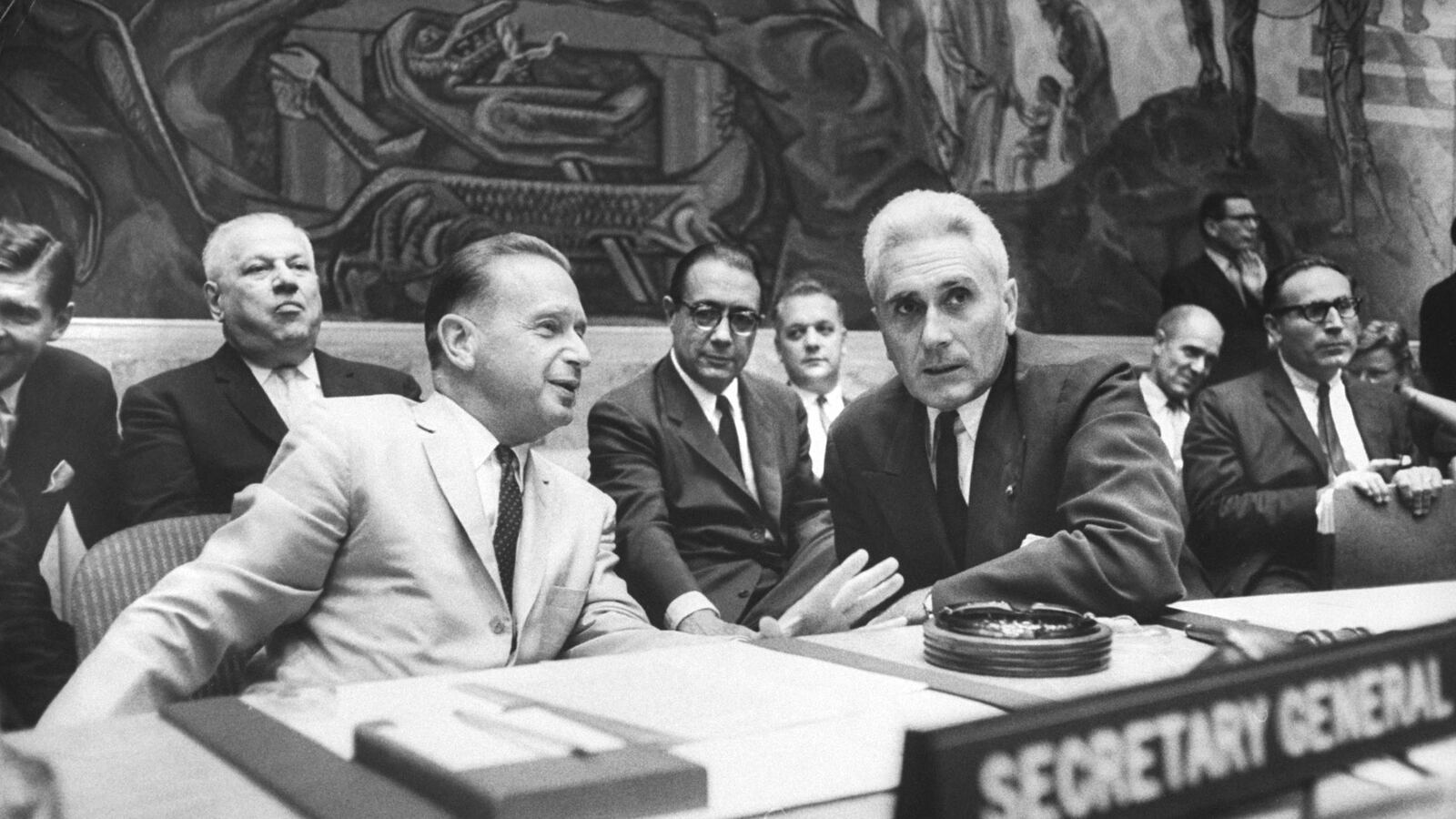

The plane’s passengers are Dag Hammarskjöld, the second-ever secretary-general of the United Nations, and his aides and security detail. Hammarskjöld was eight years into his role as Secretary-General, and heading for Rhodesia to negotiate a ceasefire with Moise Tshombe, the leader of Katanga province in the neighboring Democratic Republic of the Congo, where rebels had separated from the government soon after independence.

In the days after the crash, the Congolese capital buzzes with rumors. In Leopoldville, where hotel bars are bursting with diplomats, reporters, foreign agents and guns-for-hire, conversations are eavesdropped on and reported. An Associated Press reporter claims to hear two Belgian pilots boasting of their plane-downing deed; a United Nations officer cables rumors of KGB involvement in the crash; and the American ambassador claims it as the work of a rogue Belgian mercenary.

What happened on the night of September 17, 1961, has propelled conspiracy theories and baffled experts. A half-century later, on this past Monday, the United Nations released its second official report on the crash. The panel, comprising a Tanzanian justice, an Australian aviation expert and a Danish ballistics expert, was appointed in March by decision of the General Assembly, and traveled to the crash area, in what’s now Zambia, to track down 12 surviving eyewitnesses. But rather than deal a conclusive blow to the conspiracies, the mystery of Hammarskjöld’s untimely death prevails.

Were there really two planes in the sky? Was the aircraft already on fire when it hit the ground? Did Hammarskjöld survive only to be shot after the craft? Was the whole thing an elaborate multi-country spy conspiracy to kill the man integral to peace negotiations in a region of the world that was spiraling into East vs. West proxy battles?

Almost immediately, rumors about the real cause of the crash began to swirl. Chief among them was the belief that the plane had been purposefully either diverted or shot down, as the man inside was integral to the peace negotiations. Soon after Hammarskjöld’s death, former President Harry Truman reportedly told the press that Hammarskjöld “was on the point of getting something done when they killed him. Notice that I said ‘when they killed him.’”

In the most conspiracy-rife era of our time, when the Cold War was soliciting allegiances, perhaps nowhere was ther such fodder for a Graham Greene spy thriller than central Africa. In the recently decolonized Congo, wars for control were being puppeted from thousands of miles away.

The country had split into parts, and all sides were stocked with battalions of mercenaries, and overflowing with spies. Earlier that year, the CIA had secretly assisted in the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, the first democratically-elected prime minister, and would later install a dictator named Mobutu Sese Seko in his place.

The United Nations had its work cut out for it, and Hammarskjöld was the man on the ground striving for peace and unity. “He probably knows more state secrets than any man alive,” Parade said about him in a 1960 article. “He hides what he knows behind a cloud of diplomatic double-talk.” The year of Hammarskjöld’s death, he was awarded a posthumous Nobel Peace Prize, and he’s still the youngest person to hold the secretary-general post. But he wasn’t universally popular. Hammarskjöld’s decision to quash the rebellion in Katanga put him on the outs with the Europeans, whose mining interests in the mineral-rich province were aligned with rebel factions.

That night, far from what was then Rhodesia, strange tales were slipping out from official American agency stations. In two different National Security Agency outposts, employees reported seeing or hearing interceptions of radio transmissions that indicated an outside attack on a United Nations plane.

U.S. Navy Commander Charles Southall was stationed at the NSA facility in Cyprus. In the years after the attack, he swore that he had either heard a recording or read a radio transmission transcript where a pilot reported shooting down an aircraft that night. According to Southall, this transmission had been collected by the CIA and passed to the NSA.

At another NSA listening post in nearby Greece, a U.S. Air Force officer was listening to the radio that night and reported strange transmissions. He said he believed he was listening to American ground troops on the radio, and at one point he heard an accented voice say “the Americans just shot down a UN plane.”

He recalled hearing the pilot radio in: “I see a transport plane coming low,” he claimed the voice said. “All the lights are on. I’m going to go down to make a run on it. Yes, it’s the Transair DC6. It’s the plane. I’ve hit it. There are flames. It’s going down. It’s crashing.” He was told it was a Belgian pilot known as the “Lone Ranger,” flying a craft used by forces in Katanga, the province where Hammarskjöld was attempting to broker peace.

But the record of these transmissions either never existed, has been lost to time, or is being held in the clutches of the U.S. government.

In requesting information about radio traffic that night, the UN panel was told by the NSA that after determining that such information “exists in these documents,” it would not release them because doing so “could reasonably be expected to cause exceptionally grave damage to the national security.”

This was not taken kindly by the United Nations. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon wrote in the introduction that he will keep the investigation open and has appointed the UN legal counsel to urge United Nations member states to declassify the missing information. Because while some countries opened up files for the investigation, others, including the United States, did not, citing concerns even so many years later.

Even with a new investigation and comprehensive review of old findings, bizarre subplots and unanswered questions like these mean there’s still little closure for the tragic case file.

The afternoon after the crash, investigators discovered badly burned bodies and charred plane remnants. Fifteen passengers had died almost instantly, but one stayed alive for five more days. Before succumbing to his injuries, this man told investigators that he recalled hearing and seeing explosions aboard the plane before it crashed.

In the course of research, the UN panel interviewed nine new eyewitnesses in Zambia who claimed another plane was in the sky at the same time as Hammarskjöld’s. A number of these witnesses also claimed the plane was on fire before dropping into the forest.

The witnesses, recalling watching the crash from the ground, described “lightening” striking the plane, “army jets” flying toward the airport, and a plane falling out of the sky.

Those who visited the crash sight the next day reported strange and incongruous findings. Many claimed that the body of the plane was riddled with ammunition. One witness who came upon the crash said two Jeeps filled with men in fatigues were already there and ordered him to leave, but he observed bullet “holes the size of my fist” in the plane. He described the scene to investigators as looking “as if it had been sprayed with bullets and there was a whole row across the aircraft.”

The 1962 UN commission report that investigated the crash could not find evidence to support that the plane had been purposefully downed. But the current panel was unable to entirely dismiss the claims of a second plane or a fiery attack before the crash because not all of its remnants were examined. The panel decided it “could not completely rule out the possibility of hostile actions, such as an aerial or ground attack.”

Who were these perpetrators of the rumored attack? An alleged former CIA agent Roland “Bud” Culligan claimed that he himself had shot down the plane, but any evidence to support this is weak. A few years after the crash, two former senior UN officials, one of them Hammarskjöld’s former personal assistant, claimed to have taped interviews with a Belgian mercenary pilot called “Beukels,” who was sent to divert the plane to prevent the meeting with Moise Tshombe, but ended up shooting it down.

In 2005, a Norwegian military officer who was part of the UN Congo operation and had gone to collect Hammarskjöld’s belongings, reported that his body had a bullet hole in the forehead, but this description was not recorded in the investigations immediately afterwards, nor by autopsy or X-ray records.

That same year, a man questioned by Norwegian police told them a South African friend of his was employed to drive to the crash site and kill the survivors, including Hammarskjöld. The panel found record of the South African working in the Congo on corresponding dates, but requests to the government in tracking him down went unanswered.

While the report does dispel a number of baseless theories—conspiracies that Hammarskjöld was assassinated after surviving the crash are quashed by a conclusion that Hammarskjöld’s cause of death was a “crush injury” to the chest—it leaves many questions unsolved. The rumors are endless. Was the crew was overworked? Was the cipher machine used by Hammarskjöld to communicate with the United Nations was being intercepted by American intelligence agencies?

Most intriguingly: was the crash actually a high-level collusion between the world’s superpowers that has been successfully covered up for 54 years?

During the 1998 reconciliation process, South Africa released a series of letters allegedly written by a murky spy agency detailing a joint American-British-South African plot to kill Hammarskjöld. One of the letters says: "In a meeting between MI5, special ops executive and the SAIMR, the following emerged—it is felt that Hammarskjöld should be removed." The undated letter also claims U.S. involvement, reading: "Allen Dulles [then director of the CIA] has promised full co-operation from his people."