Come the return of museums, come the return of the blockbuster fashion exhibit. And this September, the return of an in-person Met Gala will herald the two-part, In America: A Lexicon of Fashion and In America: An Anthology of Fashion. Both encompass the history of American fashion.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute will hope the ambitious undertaking will boast the same crowd numbers that descended for shows like its Alexander McQueen retrospective and Camp: Notes on Fashion. The Met is not alone in realizing the popularity of fashion-focused exhibits. The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts hosted an entire exhibit on Thierry Mugler several years ago. The Museum at FIT has held exhibits ranging from Fairytale Fashion to Ballerina costumes.

But one perennial issue hangs over many such shows: where are the Black designers?

A spokesperson for the Met, referencing the two upcoming shows, told The Daily Beast that “these are profoundly important issues” that will be central to the two shows. “It’s best for the work to speak for itself when the shows open in September (part one) and May 2022 (part two).”

The Met did not respond for further request for comment when asked a range of questions about their efforts to include more Black artists in exhibits, if there were any potential exhibits being discussed to spotlight Black art history, or if there were any diversity initiatives to help rectify the lack of Black representation among exhibits, or how many Black curators they have.

A spokesperson for New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) told The Daily Beast that the museum had organized two fashion exhibitions in its history: Are Clothes Modern? (1944) and, more recently, Items: Is Fashion Modern? (2017).

While 1944 was eons before conversations about inclusivity in the fashion industry became mainstream, Items: Is Fashion Modern did include 10 Black designers, namely Laduma Ngxokolo, The Sartists, New Breed, Juliana “Chez Julie” Norteye, Dapper Dan, Kerby Jean Raymond of Pyer Moss, Loza Maléombho, Araba Stephens Akombi, Bernadette Thompson, and Nana Kwaku Duah.

A spokesperson said that over the last 10 years, MoMA had worked with “purpose and urgency” to confront the gaps in its collections and exhibition programming, and to collect and present more art created by women and people of color. Research and collaboration leading to exhibitions like Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960-1980 (2012), Charles White: A Retrospective (2018), also led to multiple acquisitions of work by the artists included. Adrian Piper: Synthesis of Institutions 1965-2016 (2018) directly confronted issues of deep-rooted systemic racism in both museums and America and remains the largest exhibition of a living artist in the MoMA’s history.

MoMA also has the Fund for the 21st Century, a trustee fund committed to purchasing contemporary work for MoMA by emerging artists that have helped them make important acquisitions of work by women and BIPOC artists. Examples include major installation works by Cameron Rowland and Sondra Perry, both very early in the artists’ careers.

In 2019 at their reopening, many galleries within the collection gallery circuits highlighted work by Black artists, including Faith Ringgold, Jacob Lawrence, Pope.L, Benny Andrews, David Hammons, Roy de Carava, and William H. Johnston.

A MoMA spokesperson told The Daily Beast: “The Museum came together in new ways, after the brutal murder of George Floyd last May, to confront issues of systemic racism and inequity and catalyze its anti-racism efforts.” The spokesperson said that six BIPOC staff members had been invited from different museum departments, each at different points in their respective career experiences, to form a Diversity, Equity, Accessibility and Inclusion (DEAI) Steering Committee.

“The committee is independent and interdepartmental and it seeks everyone’s participation in a process that prioritizes the well-being of BIPOC staff—and therefore all staff—to thrive at the museum. It has full authority to work with any and all groups it wishes to within our museum and to engage outside support as needed. Its purpose is to lead and collaborate across the museum to build an inclusive process for positive change, and its impact to date is clear: a new visitor code of conduct, facilitated listening and discussion sessions with BIPOC staff, an all-staff introduction to the science of implicit bias, and the launch of an assessment phase of the museum’s race equity work with its DEAI accountability partner: soliciting staff perspectives, experiences, and opinions through surveys, focus groups, facilitated conversations, and drop-in sessions that are critical to shaping a successful DEAI plan for MoMA. That work continues.”

The Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago has also made space for Black designers in its show schedule. In 2019 they held Virgil Abloh: Figures of Speech, an exhibit dedicated to the Off-White creative director and arguably the most prominent Black luxury fashion designer.

A spokesperson for the museum told The Daily Beast, “While we do not have any upcoming exhibits of Black fashion designers, as an ongoing initiative we regularly collaborate with BIPOC designers (Hebru Brantley, Joshua Vides, Lorraine West, JoeFreshGoods, Lingua Nigra) on exclusive lines and products that are sold through the MCA Store.” The Museum’s current exhibition, Chicago Comics: 1960s to Now, also puts a spotlight on BIPOC comic artists and cartoonists.

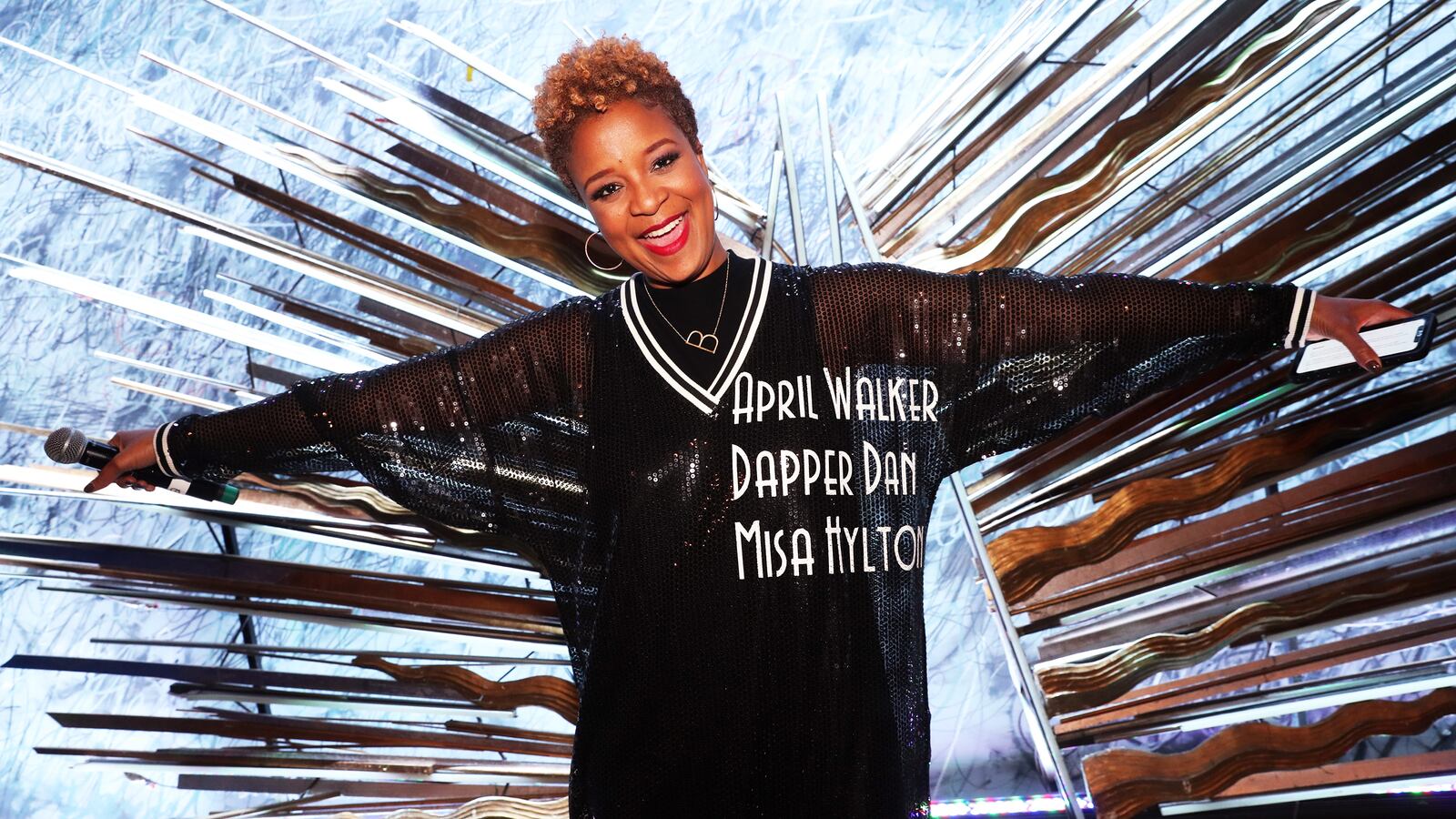

Brandice Daniel, the founder of Harlem Fashion Row, considers studying Black fashion history a personal hobby of hers. She had the opportunity to meet Lois Alexander Lane, the founder of the Black Fashion Museum in Harlem, which sadly closed in 2007.

“People do not realize how deep Black fashion history is,” Daniel said. “People don’t realize Rosa Parks was a seamstress. She was in the middle of making a dress when she was arrested for refusing to move for a white passenger on the bus. That dress was later exhibited in a fashion show that Lois Alexander Lane had. When you start digging into Black fashion history, it is so rich. The women who were making dresses on plantations during slavery were Black slaves making dresses for society women. Those dresses were the modern equivalent of couture.”

Daniel acknowledges that the conversation around exhibits lacking Black designers is very new, but she views it as more reactive than proactive. “People are more concerned with what people are going to say if Black designers are excluded from exhibits rather than actually including Black designers,” Daniel said. “Museums haven’t done a proper exhibit to really celebrate and inform people on the contributions of Black fashion.”

The story of Black art in museums and who curates the art on display is much larger than the Met and MoMA. In 2019, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, in partnership with the Association of Art Museum Directors, the American Alliance of Museums, and Ithaka S + R, conducted a comprehensive survey of the ethnic and gender diversity of the staffs of art museums across the United States.

At the time, the survey found that the number of Black curators increased from 2 percent in 2015 to 4 percent in 2018, an increase of 21 positions. However, the survey also find that at senior positions—including museum director, CFO, and CEO—there was literally no change in regard to race and ethnicity, with senior leader positions only seeing a 1 percent diversity increase from 2015 to 2018.

Pamela Edmonds, a Canadian-based curator, describes herself as a “decolonizer” of art spaces and museums. Over her 20-year curatorial career, she says it is only within the last five years has she really seen things change in terms of work by Black artists being included in museums.

“In the ’90s, there was a lot of talk around identity politics in the museum and art communities, but then in the ’00s there was a backlash against identity politics,” Edmonds said. “After last year with all the civil rights protests, the conversation around social issues and identity politics was full-on again. Black creatives used to be treated like they were restricted to just getting work during Black History Month, and after that finding work was like being stuck in the desert. It was tokenism. Institutions just wanted to check off boxes to say, ‘We did the Black show.’”

According to Edmonds, museums are inherently white and colonial in their very existence because that is the foundation upon which they were built, but she added, “That doesn’t mean we can’t reimagine these spaces and create different models and conversations. Museums can be gathering spaces for communities to have conversations around life and culture. Even with exhibitions with largely European collections, works can be used to explore decolonization. It’s about the narrative you build around it and creating conversations relevant to the moment. I had a show of mostly European works and used Sun-Ra for the background music. It’s possible to have inclusivity with all types of work on an exhibit.”

Edmonds says that because of protests and work on anti-racism, “Museums are looking at their collections, their board of directors, and being called to be accountable. I’m seeing a lot of anti-racist policies and efforts toward inclusion. You didn’t see that five years ago. Black folks are engaging art in a way that is multidisciplinary, from contemporary art to fashion. With people becoming more media specific, museums have had to expand their horizons and open their doors to more of these creatives.”

Edmonds said with increased awareness over how Black creatives have been excluded from museum spaces, there’s more people calling them out. Dominique Fontaine, an art curator and consultant who is the founder of aPOSteRIORi, a non-profit curatorial platform, is focused on diversifying art and museum spaces.

Fontaine says the reason Black creatives have been excluded from museum spaces is because “in art history programs, there is almost no mention of Africa. The only mentions of Africa are Egypt. It takes much more research to educate yourself on Black cultural productions, but there are places with Black arts movements that are very proactive, but Western institutions don’t make it easy for people to bring Black bodies into white institutions. We have to prove that Black people can occupy these spaces.”

Fontaine says more Black representation will come in museum exhibits once there is more representation across the board. “We need to advocate for representation not only on the museum walls, but on the board of directors, on staff, and everyone from the lowest to the highest level from the security guards to the executives at the top. Black people are capable of occupying every space across the board and being part of every discussion.”

Fontaine says to ensure that there are Black professionals get the opportunity to occupy these spaces, museums need to reevaluate their hiring processes to guarantee diversity and inviting more Black people to be on their boards of directors.

Fontaine says that her feelings regarding institutions making tangible change for Black people is best summed up by Ohio State University’s Dr. Monica F. Cox, who tweeted: “Instead of showing me your diversity statement, show me your hiring data, your discrimination claim stats, your salary tables, your retention numbers, your diversity policies, and your leaders’ public actions against racism.”

In her efforts to preserve and foster Black fashion history, Brandice Daniel has created an E-book called Fashion in Color: Preserving the African American Legacy in Fashion. Daniel’s colleague Kimberly Jenkins, an assistant professor of fashion at Ryerson University, is also compiling The Fashion and Race Database to provide information about Black designers and Black fashion history for museums, brands, colleges, and universities to use.

Daniel said that the exclusion of Black designers from museum exhibits has, “caused Black people to never realize what a big role we have played in the fashion industry, nor does the fashion industry acknowledge that. Museums can frame history in a way that would help people see the value of Black creatives. That’s the role museums play. Black designers not being exhibited leaves the fashion industry uninformed and leaves people of color walking into this industry feeling like outsiders, meanwhile we’ve laid so much of the groundwork for fashion as we know it.”

Daniel said one of the reasons addressing these issues is difficult is because non-Black people have been so uncomfortable having conversations about race, and until those conversations can happen more openly there is a roadblock in addressing how to amplify Black voices and guarantee Black representation.

“Black fashion designers and industry professionals have this treasure that we have not uncovered,” Daniel said. “I would love for museums to start to uncover and discover all of the impact Black people have had on the industry. Museums need to do consider doing something over the next few years that will do Black fashion history justice.” Daniel says one of the critical components to making sure this happens is making sure there are more Black curators and consultants.

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History & Culture (NMAAHC) in Washington, D.C. has led the way in preserving Black fashion history. In 2007, it inherited the Black Fashion Museum collection of of more than 2,000 objects including garments, hats, and accessories.

In a statement e-mailed to The Daily Beast, Elaine Nichols, NMAAHC’s fashion curator, said, “The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture is painfully aware of the racial and gender disparities that exist within the global world of fashion. We have intentionally identified and collected objects and research data related to black, women and LGBTQ+ fashion designers.”

In September 2016, when NMAAHC formally opened to the public, at least half of the Inaugural Exhibitions highlighted black fashion designers. Galleries that featured various fashion and costume creations by Black designers included one featuring a dress designed by Tracy Reese and worn by then-First Lady Michelle Obama in connection with the 50th Anniversary of the March on Washington.

In addition to including Black designers and fashion in a multitude of exhibits, the museum also has two curators who serve as resources for scholars and the public seeking information about African American and African diasporic dress and fashion. They receive and respond to numerous requests for information related to the museum’s dress and fashion collections.

As a Black-focused museum, NMAAHC has had no issue with Black representation. The overwhelming majority of the museums curators are Black, and they continue to ensure the majority, if not all works at the museum are directly connected to the African diaspora. Prior to the larger national conversation around Black inclusivity being a major part of the 2020 headlines, NMAAHC was a part of the Smithsonian’s public programs.

Next, NMAAHC is planning a symposium on Fashion, Culture, Futures: African American Ingenuity, Activism and Storytelling scheduled for this October. In collaboration with Cooper Hewitt, the symposium will explore the history of Black people in fashion, offer dialogue with black models, and LBGTQ and transgender fashion icons, and examine the future impact of fashion on marginalized communities of color.

While the road for inclusivity is still lengthy, the work is slowly being done. As Daniel puts it, “Having Black voices in the room is crucial to representation.”