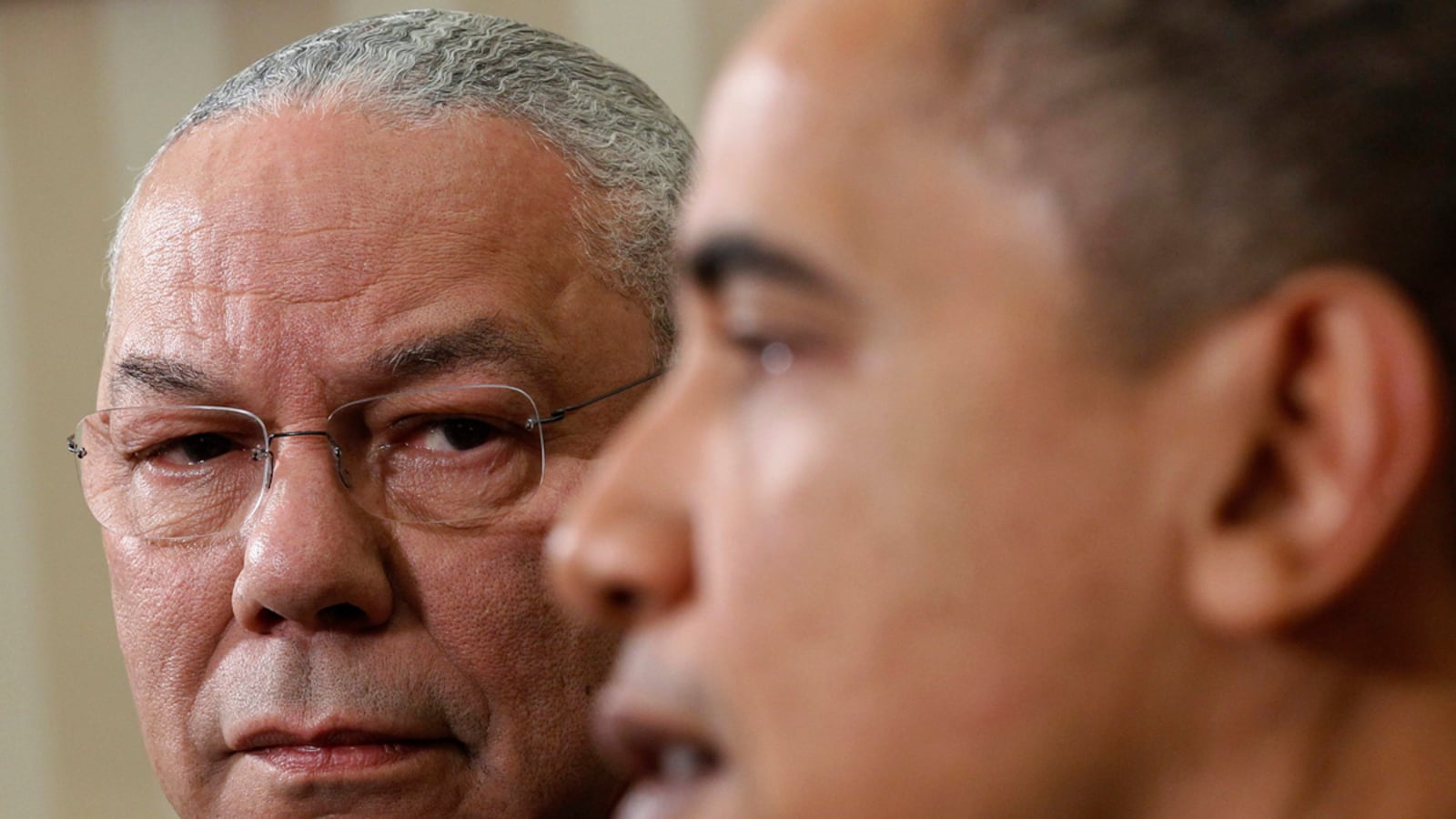

Prominent Republicans seem genuinely surprised that Colin Powell has endorsed Barack Obama, again. So baffled was Romney adviser John Sununu that he chalked Powell’s decision up to racial solidarity. But that’s silly. African-Americans motivated by racial solidarity don’t spend their careers serving Republican presidents. Powell’s real tribal motivation, I suspect, is more interesting, and more significant. He’s backing Obama because he thinks Obama’s better for the U.S. military.

The welfare of the military has always been the prism through which Powell sees American foreign policy. His two tours in Vietnam, during which he saw “recently health young American boys, now stacked like cordwood,” bred in him a deep distrust of optional wars and the civilians who launched them. It was reinforced when, as an aide to Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger in 1983, he received the late-night phone call with the news that hundreds of Marines had been blown to bits in Lebanon.

Powell spent the rest of his career battling the conservative neo-imperialists, and the liberal hawks, who wanted to use the Soviet Union’s demise to extend American power at gunpoint. “War is a terrible thing with unpredictable consequences. I can’t predict the consequences, I fear them,” Powell told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee during a December 1990 hearing on the impending Gulf War. In fact, Powell’s vociferous objections to the war won him a tongue-lashing from then–defense secretary Dick Cheney, a man who—Powell acidly noted—had received multiple deferments from Vietnam. When the Bushies left office, Powell skirmished with Secretary of State Madeleine Albright over the Clinton administration’s desire to go to war to save Bosnia.

After 9/11, Powell initially opposed sending ground troops to Afghanistan, declaring at a Sept. 23 White House meeting, according to Bob Woodward, that “It is not the goal at the outset to change the [Taliban] regime.” And in private, he urged containing—rather than overthrowing—Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, in part because he doubted the military could fight successfully in Iraq and Afghanistan at the same time.

Given all this, it’s easy to imagine why Powell might not be wild about Mitt Romney, another son of privilege who backed the Vietnam War but received multiple deferments so he didn’t have to fight there himself. (In his memoir, Powell writes that, “I can never forgive a [political] leadership that said in effect: These young men—poorer, less educated, less privileged—are expendable … but the rest are too good to risk.”) And it probably didn’t escape Powell’s attention that Romney—who originally opposed Obama’s troop withdrawal date in Afghanistan and wants to lower the bar for war with Iran—never visited Afghanistan during his international tour this summer. Romney also never mentioned the troops there during his convention acceptance speech or during the first debate. It’s a good bet that Romney strikes Powell as the kind of chest-thumping civilian who wants to outhawk his opponent without knowing, or caring, all that much about the young Colin Powells whose lives he might endanger as a result.

Recent polls offer a mixed picture of whom active-duty military personnel, and veterans, support for president. Some may like Romney’s promise to boost defense spending, though it’s unlikely that impresses Powell, who in the early 1990s pushed for larger defense cuts than the first Bush administration would permit.

But when twinned with the military brass’s apparent resistance to military action against Iran, Powell’s endorsement of Obama does reflect a significant shift. Since Vietnam, the United States military has generally been both resistant to military action and culturally distrustful of Democrats. In the Obama era, however, the culture clashes that estranged Democrats from the military between the 1970s and the 1990s have receded. Unlike Bill Clinton, Barack Obama was too young to either evade, or protest, the Vietnam War. And today, unlike in the 1990s, the military no longer fiercely resists the service of openly gay and lesbian troops.

After a decade of disastrous invasions, on the other hand, the military’s fear of unwinnable war has never been greater. And the Republicans who share that anxiety—men like Brent Scowcroft, George H.W. Bush, James Baker, and Colin Powell—have become largely irrelevant to the party’s foreign policy. Under these circumstances, it’s not surprising that Powell would see in Barack Obama a more trustworthy commander in chief. Colin Powell isn’t obsessed with race. He’s obsessed with reckless foreign policy. Other Republicans should try it some time.