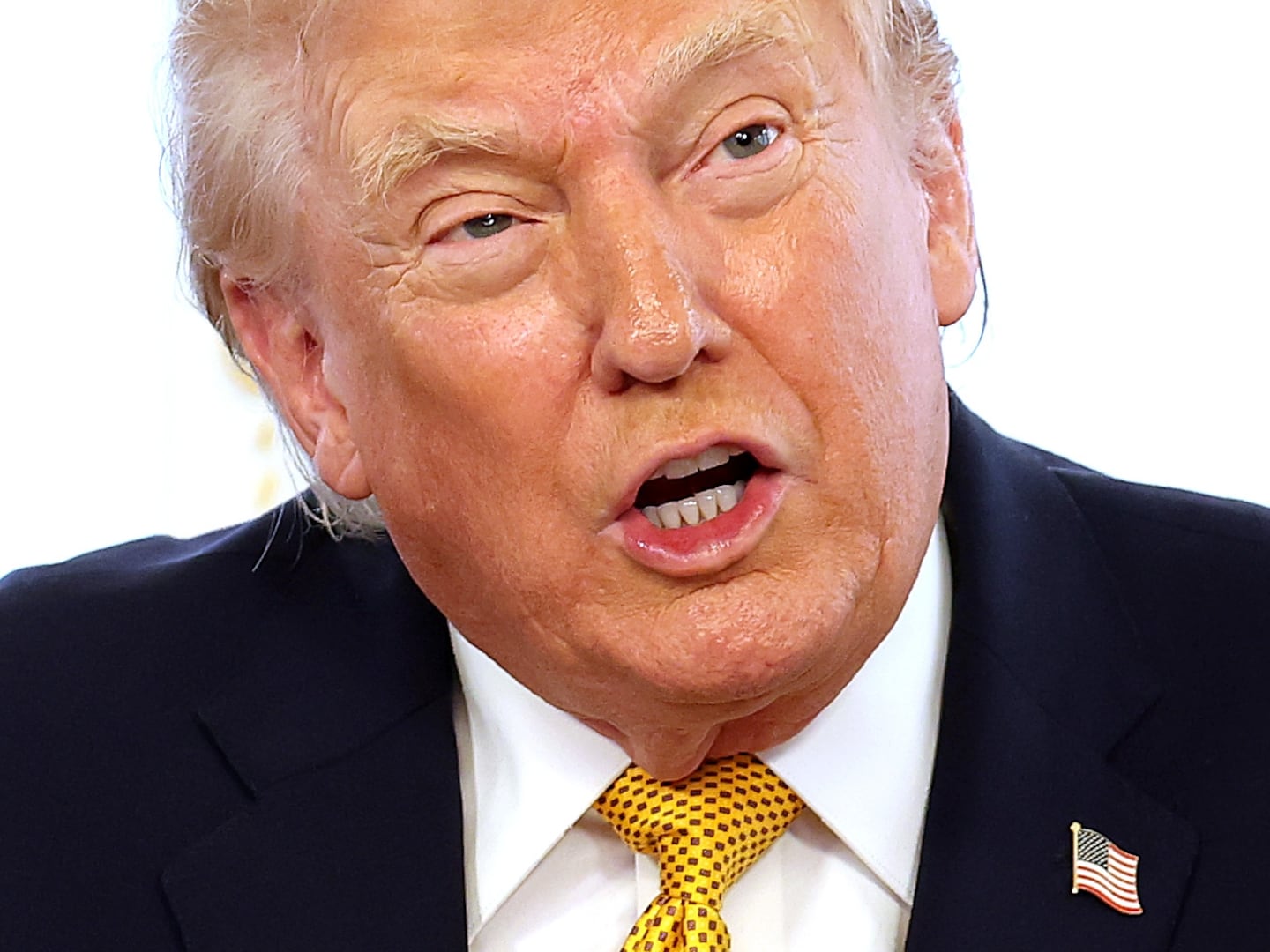

Thus far, most reactions to the indictment of former President Donald Trump have fallen into two depressing categories: rejection by his fans and cheers by his opponents.

I suspect this is not where the middle third of the American public—i.e., the chunk of the population that generally decides presidential elections—stands.

For all the poll data showing Trump’s support among the MAGA faithful, for whom the growing shelf of indictments is evidence of persecution rather than prosecution, many independents and moderates are, it seems, waiting to see what comes of the legal processes presently unfolding in (checks notes) three jurisdictions as of today.

One such voice, Republican congressman turned libertarian influencer Justin Amash, recently weighed in with a 225-word tweet opposing the indictments. “I may not like Trump,” it began (with significant understatement, given that Amash’s courageous defiance of Trump ultimately cost him his congressional career), “but I love our Constitution, so I feel compelled to speak out.”

Because ex-Rep. Amash’s take likely reflects what many independent-minded people are thinking, it merits a closer look. Because it is also quite wrong.

In a way, Amash’s argument is a more nuanced version of the Republican party line: that the indictments are political, not criminal. Referring to Trump’s misdeeds, he says they constitute “precisely the sort of wrong that must be addressed politically under our Constitution, not criminally.”

But he continues with a tongue-in-cheek analogy: “Remind me again which former presidents have been indicted for going to war without congressional approval, spying on Americans in violation of the Fourth Amendment, abusing emergency declarations to bypass checks and balances, or ignoring legal advisers to pursue a clearly unlawful policy.”

And so, he concludes, “We don’t criminalize these actions, egregious as they are, because they are matters of political contention. We’re allowed to disagree about the workings of our constitutional system without fear of criminal reprisal… It endangers all Americans to begin treating politicians’ false beliefs regarding political or constitutional matters, even when they’re obviously wrong, as criminal offenses.”

In principle, Amash’s argument makes sense. In practice, it does not.

First, let’s dismiss its weakest point: that the indictments are about Trump’s “false beliefs.” That is obviously not true. The indictments aren’t about Trump’s beliefs; they’re about how he conspired with advisors and government officials to throw out legitimate election results, and exploited a riot to try to force Congress to do so as well.

Amash’s argument is stronger when it comes to presidential misdeeds, but it still collapses.

His examples are all about the nebulous gray zone of executive power, actions which libertarians may believe to be unconstitutional, but which the Supreme Court does not: “going to war without congressional approval… spying on Americans… abusing emergency declarations… [and] pursu[ing] a clearly unlawful policy.”

Setting aside the tautological last element, these are all acts in which multiple presidents have engaged, with tacit or overt approval from Congress and the courts. They may indeed be symptoms of an imbalance of power, but they are not unconstitutional, let alone criminal.

In contrast, like Amash, I recommend that you read the indictment itself. Unlike the rhetoric one finds on both left and right, it is sober and meticulous. And it makes clear that there is also no analogue in American history, let alone the examples Amash cites, for the crimes Trump allegedly committed following the 2020 election.

There is no analogue for the Big Lie, which a majority of Republicans now believe. Not since the racist lies of slavery and Jim Crow has a profound untruth been so widely promoted, in contradiction to all available evidence, and with such terrifying success.

But remember: Trump’s crimes aren’t believing and spreading the Big Lie, which is protected by the First Amendment. They are the concrete actions he took to violate the Electoral Count Act of 1887: attempts to change or ignore vote tallies, the selection of “alternate electors” in seven states, efforts to enlist the Justice Department to perpetuate a fraud, and the exploitation of the violence on January 6.

One of the crucial elements of the indictment is that Trump knew he was lying, and told numerous people that he knew he lost, (§ 11) yet still took numerous actions to try to get public officials to throw out legitimate election results. That has never happened before in American history, not on this level anyway.

As the indictment states in exhausting, damning detail, Trump tried to get everyone from governors to secretaries of state (§ 13-69) to Justice Department officials (§ 70-85) to the vice president of the United States (§ 86-95) to effectively burn the ballot boxes and declare him the winner. That is absolutely nothing like the potential excesses of presidential power that Amash cites.

Finally, of course, there is no analogue in American history for Jan. 6. As anyone watching the news that day remembers, it was completely unprecedented: a violent mob, egged on by a still-sitting president, invaded and attacked the United States Capitol. But for the heroism of a few law enforcement officers, they may well have murdered numerous government officials.

Once again, the indictment exhaustively documents Trump’s tweets, exhortations, actions, and attempts to leverage the violence to defraud the United States, obstruct the governmental function of certifying the Electoral College, and deprive voters of their right to vote. (§ 96-124)

These are not political decisions. They are, if proven true, crimes. As the indictment states, they “target[ing] a bedrock function of the United States federal government: the nation’s process of collecting, counting and certifying the results of the presidential election.” (§ 4)

Yes, presidents may sometimes overreach, and if they do so, Amash is correct that their misdeeds should be corrected by the electoral process in most cases, impeachment in extreme ones.

But trying to throw away lawfully-cast ballots isn’t in any way like that. It’s not even like lying under oath (Clinton), plotting and covering up a burglary (Nixon), or attempting to bribe foreign leaders (Trump). It contains all the elements of a criminal conspiracy to commit fraud and the criminal obstruction of a governmental function. And Trump is, to this very day, repeating the lie at the heart of it, and promising, if elected, to once again weaponize the federal government on the basis of it.

The actions described in the indictment aren’t political decisions. They aren’t even just crimes. They are crimes that the criminal has promised he will repeat if given the chance to do so.

In short, they are exactly the kinds of unlawful acts from which the rule of law is meant to protect us.