When was the last time you saw the stars? Think about it. Try to really recall the last time you saw a constellation like the Big Dipper, or spotted the North Star on the horizon.

If you live in a rural part of the country, there’s a good chance you’ve seen them as recently as last night. However, if you’re one of the nearly 40 percent of Americans who live in a city, you might not have seen them last night or the night before. If you live in a large city like New York or Los Angeles, there’s a good chance you don’t even remember the last time you saw the stars.

While it might not seem like much, our ability to see the stars at night is actually a pretty good indicator of not only the overall health of a city, but also its surrounding ecosystem. And the visibility of the night sky lets researchers know about other pernicious and potentially devastating issues within communities that are largely unseen but can result in the deteriorating health and increasing disparity for society at large.

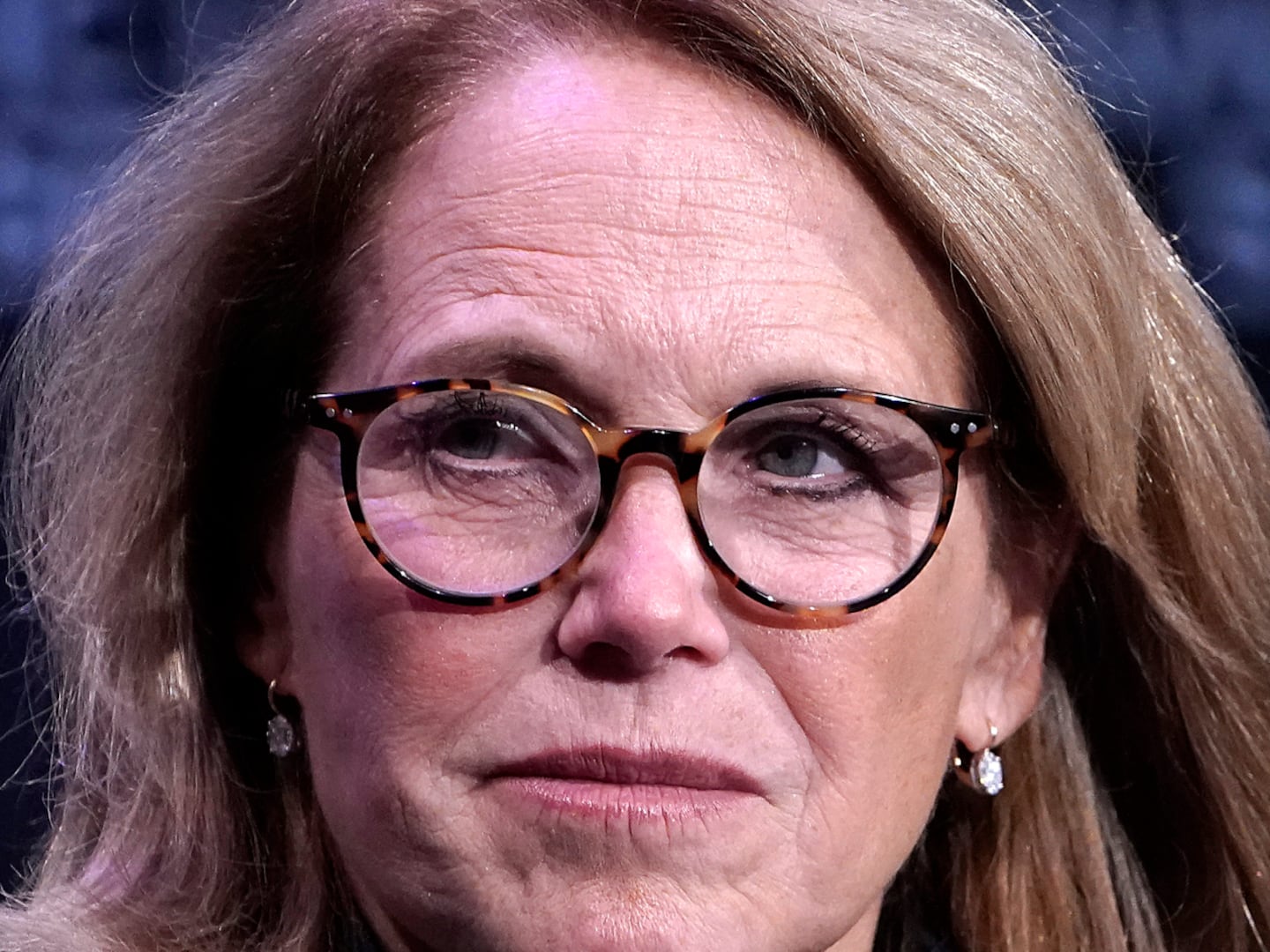

“We should be more cognizant of it,” Eva S. Schernhammer, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, told The Daily Beast. Throughout her research, Schernhammer has uncovered a number of troubling links between overexposure to light and health issues. She led a 2001 study that found a strong link between nurses who work at night and an increased risk of breast cancer.

More recently, Schernhammer co-authored a paper published June 15 in the journal Science about how reducing artificial light at night (ALAN) could improve “human health and society.” The paper is one of several published in a series dedicated to ALAN and its deleterious effects on everything from health, to the ecosystem, to the field of astronomy as we know it.

Some of the findings are enough to make you want to flip the switch off for good. For example, a staggering 83 percent of the world’s population lives under light polluted skies. This represents roughly one-fourth of the Earth’s overall landmass. This number is also growing at a breakneck pace of 11 percent each year, and is exacerbated by the growing number of satellites being shot into orbit by private space companies such as SpaceX—resulting in a kind of perfect storm of disappearing darkness.

The looming effects mean more than just the loss of the night sky, according to the papers’ authors. They also represent an existential risk to the public health and the stability of natural environments. It is not alarmist to suggest light pollution is going to result in increased rates of hospitalizations, and even the emergence of new diseases.

“What worries me most about that—apart from the fact that we still need to better be able to measure it so we understand its direct impact on humans—is its impact on our ecosystems,” Schernhammer said. “It impacts the habitat of animals. When they get under stress, they may be triggered to express more of the viruses that live in them. That, in turn, can come back to us.

That’s right: The next pandemic might occur because it’s too bright out.

The Sound of Silence

The flipside to light pollution’s coin is also something we’re ignoring at our own peril. Mississippi artist Erica Walker has a story that will probably sound familiar—perhaps too literally. A few years ago she had been experiencing something many of us have gone through at one time or another: noisy upstairs neighbors. The situation got so bad, she began looking into ways that she could get her neighbors to quiet down via the legal system.

As she gathered her data and information to make her case, though, she discovered that she wasn’t alone with her issue with noise. “I realized that it was just a much bigger problem than myself,” Walker told The Daily Beast. “There was a big problem.”

Today, Walker is an assistant professor of epidemiology at Brown University School of Public Health where she also helps run the Community Noise Lab, which explores the relationship between community noise and public health. Her research has unveiled a stark link between noise pollution and the overall well-being of communities.

A recent analysis by The New York Times underscored the pervasiveness of this issue well. In one study published in 2019 in the European Heart Journal, scientists researched the brain scans of hundreds of patients and found that those who lived in areas with loud transportation noises like airports and railways were more likely to have major cardiac events and heart ailments. Another study published 2021 in the European Heart Journal found that hearing airplane noise within two hours of sleep increases your likelihood of experiencing a sudden heart attack.

Noise pollution isn’t just limited to airplanes and trains either. It can occur if you live near a busy road with a lot of traffic, or if you’re in a neighborhood with a vibrant nightlife, or even if you live with noisy neighbors like Walker did before. This “acoustical trash” as Walker refers to it, disrupts our sleep, increases production of stress chemicals like cortisol, and triggers our fight-or-flight response that stresses our physical and mental well-being.

In her research, though, Walker has also discovered that there’s a link between noise and light pollution—these aren’t simply discrete sources of disturbance and havoc. Often, when she finds a source of noise pollution in a community like an Amazon distribution center or a railway, she’s likely to find the other.

“Things like light pollution, noise pollution, soil pollution don't happen in a vacuum,” Walker explained. “When you find one, you find them all. If there's light pollution somewhere, there's noise pollution. If there's noise pollution somewhere, there's probably water pollution. They're like these sort of canaries in the coal mine for other things. They’re all connected.”

Uneven Noise

Like most forms of pollution, there’s a disparity in who exactly experiences noise and light pollution too, according to Walker. The communities that bear the brunt of noise and light pollution tend to be made up of people of color in low income neighborhoods—damaging artifacts of old racist and biased city planning systems that hurt poor, urban areas the most.

“It’s not only poor planning, but also intentionally harmful planning that has created this system,” Walker said. “We have to reevaluate that planning and actually do something different.”

Walker acknowledged that it will require a massive fundamental and systemic change in order to bring about the change necessary—but it’s imperative if we want to see these communities thrive. After all, they’re currently caught in a vicious and life-threatening cycle when it comes to noise and light pollution.

People who live in places with a lot of ALAN and surrounded by constant, disruptive noise suffer from poorer mental and physical health when compared to affluent communities who can avoid such issues. This, in turn, can result in a decreased chance of finding and securing a well-paying job. Likewise, children who live in these communities struggle more in school, which results in decreased rates of education.

This isn’t just hearsay either. Numerous studies have found that noise pollution disproportionately impacts low-income, minority neighborhoods when compared to their affluent, white counterparts. The same goes for light pollution too.

All of it is caused largely by the same mechanisms that drive anthropogenic climate change: out-of-control industrialization and a wanton disregard for the communities and ecosystem that make for a healthy planet. This often results in poor and historically disenfranchised populations bearing the brunt of our destructive habits.

The situation isn’t hopeless. Both Walker and Schernhammer stress the need for sound policy regulating the amount of noise and light certain places can produce in a community. Walker pointed out that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) used to have an Office of Noise Abatement, that was created in response to what they discovered to be a third of the U.S. population was “exposed to sound levels deemed harmful to their health.” However, the office was shuttered during the Reagan administration and not opened again.

Nevertheless, the same policies that can help keep climate change at bay—like rules about what industries can be built and work in certain municipalities and ecosystem protection laws—can also do the work of guarding these communities from noise and light pollution. Remember: It’s all pretty connected.

Of course, the real irony is that all of us have brought the noise and light pollution into our very own homes in a way. You’re likely reading this article on such a device right now. Walker admits that even she falls prey to this when she plays Candy Crush on her phone with her headphones on well into the night.

But that just brings the truth that we need to have a fundamental shift in our relationship with a rapidly advancing world to light.

“It’s an attitude shift,” Walker said. “It's so easy to just put your acoustical or light trash in someone else's yard and they’re not going to fight back. Our country runs on that. It runs on these inequalities. That means that we have to disrupt the very elite system of society.”