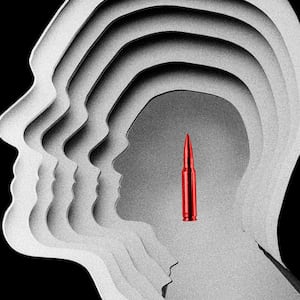

Hours after a gunman in Uvalde, Texas, massacred 19 children and two teachers, the horror of the worst school shooting since Sandy Hook was compounded by numerous conflicting reports and gaps in information about the shooting from state law enforcement and Gov. Greg Abbott.

Contrary to initial reports, there was no confrontation between the gunman and a school police officer. In fact, according to later reports from the state police, a school officer was not even on the campus when the gunman entered the building.

Four days passed before the Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS), the state police agency whose Texas Rangers are currently leading the investigation, reported that an hour elapsed between police officers entering the building and the moment when a tactical team that included Border Patrol agents charged the classroom. According to DPS’s latest version of events, officers were held back by the commander on the scene, an officer with the school police. Four days and numerous press conferences and media interviews later, parents were informed that children inside the classroom with the gunman were calling 911 begging for help while the police waited outside.

Frustrated and outraged, Rep. Joaquin Castro (D-TX), whose district includes San Antonio where the victims received medical attention, fired off a letter to FBI Director Christopher A. Wray on Friday, requesting the agency exercise its “maximum authority to thoroughly investigate the timeline of events and law enforcement response.”

People visit memorials for the victims on May 26 in Uvalde, Texas.

Michael M. Santiago/Getty“I lost confidence in [Gov. Abbott and DPS] being able to take the lead and offer the public and, most of all, offer the families of Uvalde a comprehensive and accurate accounting of what happened,” Rep. Castro told NPR. Days later, on Sunday, the Department of Justice (DOJ) announced it will conduct a Critical Incident Review with a focus on the actions and responses of law enforcement. When asked at a press conference about Castro’s letter, DPS Director Steve McCraw said the department welcomes the FBI’s involvement.

To anyone who has tangled with DPS in the pursuit of police information, as I have done over the last year with the help of two First Amendment law clinics, skepticism aimed at DPS and the governor is not only justified, it is urgently needed.

“Secrecy and Propaganda”

Until now, transparency and accurate information about the massacre in Uvalde—which is 80 miles southwest of San Antonio and 60 miles from the border—has relied on state officials and a law enforcement agency which has cloaked its policing campaigns in South Texas with secrecy and propaganda.

Under the governor and state police agency, a parallel criminal justice system has been constructed that exists largely beyond public scrutiny. Parents, the public, and press are expected to obtain vital information from a state police force that has resisted releasing basic arrest reports connected to its multi-billion dollar border security campaign, dubbed Operation Lone Star (OLS).

When government agencies, including DPS, attempt to refuse to release records, their first stop is the state’s attorney general, Ken Paxton. Texas’ top enforcer of the state’s open records law, Paxton is under indictment on criminal securities-fraud charges and federal investigation related to allegations of abuse-of-office and bribery made by whistleblowers in his office. A strong supporter of Operation Lone Star who attempted to overturn the 2021 election results, Paxton recently made news after defying an order to release his records related to the Jan. 6 insurrection in the U.S. Capitol.

Launched as an effort “to combat the smuggling of people and drugs into Texas,” Operation Lone Star was equal parts law enforcement and political operation. “The crisis at our southern border continues to escalate because of Biden Administration policies that refuse to secure the border and invite illegal immigration,” said Gov. Abbott.

Gov. Greg Abbott speaks during a tour of the U.S.-Mexico border wall on June 30, 2021 in Pharr, Texas.

Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post via GettyThe operation quickly launched Abbott into primetime newscasts where he boasted of hundreds of criminal arrests and referrals by state troopers to Border Patrol. Big claims came with few details. Were the arrests for murder or joints, rape or robbery? Requests for detailed information went ignored for months.

With the assistance of the Cornell Law School First Amendment Clinic, we waged an open records battle, and DPS ultimately delivered a spreadsheet—with no details about how the arrests occurred.

Pushed for the complete arrest records, DPS estimated its officers needed nine months to compile the records that presumably formed the basis for the governor’s claims—setting a delivery date within weeks of the gubernatorial election. In recent months, it has now become necessary for attorneys at Cornell to partner with SMU Dedman School of Law to obtain what are simply basic police records.

A team of journalists from Texas Tribune, ProPublica, and the Marshall Project encountered similar resistance. “A year into the initiative, Abbott, DPS and the Texas Military Department have fought two dozen public records requests from the news organizations that would provide a clearer picture of the operation’s accomplishments,” they wrote.

Abbott later expanded the OLS mandate to include the interrogation of migrant children by DPS troopers. In response to open records requests submitted last year, DPS stated, “Other than this Press Release, the Department has no directive to provide you.” The department then appealed to the state attorney general to block the disclosure of any information related to the apprehension and interaction with children.

It’s this labyrinth which the public, parents, and the press will likely confront when seeking answers about the massacre in Uvalde. Such stonewalling, however, fails to account for the state’s creation of a criminal system that one defense attorney likened to Alice in Wonderland.

Prior to OLS, when troopers referred people to Border Patrol, each incident was documented on a form called THP—Illegal Alien Referral Reports—which were publicly available. With the launch of the operation, DPS incorporated all of the referrals into new sets of incident reports. In briefings to the attorney general, DPS argued against the release of previously public records, citing the state’s Homeland Security Act.

Central to OLS has been the state’s gambit to prosecute migrating people who enter Texas on criminal trespass charges. Following an arrest, according to interviews with defense attorneys, civil rights complaints filed with the federal government and news reports, people are funneled into a newly created byzantine criminal legal apparatus system where people are detained, not in county jails, but in state prisons on misdemeanor charges.

In a joint letter to the Department of Justice, a coalition of public defense attorneys from across the nation wrote: “the shadow criminal legal system operates with its own dockets, booking, and detention facilities, as well as hand-picked judges and separate defense attorneys.”

In a complaint filed with the DOJ, attorneys with the Texas Civil Rights Project and the American Civil Liberties Union of Texas wrote: “Much information regarding the OLS trespass arrest program is difficult or impossible to access. We have been unable to secure access to records for all arrests to date, even though they are open records.”

Most of the OLS-related trespassing arrests claimed by DPS, according to an analysis of the spreadsheets provided by the department, have occurred in Kinney County—which neighbors Uvalde. Local and state officials have peddled nativist and white supremacist rhetoric to justify OLS, according to the civil rights complaint. Weeks before the massacre, Uvalde’s majority-white county administration, which governs a majority Latino population, expanded the DPS-led migrant arrest operation into Uvalde. DPS troopers, which had saturated the region, responded to the call on May 24 that a gunman had entered an elementary school.

Director and Colonel of the Texas Department of Public Safety Steven C. McCraw speaks at a press conference using a crime scene outline of the Robb Elementary School showing the path of the gunman, outside the school in Uvalde, Texas, on May 27.

Chandan Khanna/AFP via GettyAfter initial DPS reports that were later changed, DPS Director Steve McCraw and Border Patrol sources told reporters that agents and officers were held back from charging into the classroom by the scene commander, who works for the school police.

“Now they are trying to pin everything on this ISD (independent school district) chief,” said Scott Henson, executive director of Just Liberty and the author of the blog, Grits for Breakfast—a must-read source for critical reports of Texas’ police and criminal justice system. “The reality is that I think that’s a red herring in this situation. “They have now come up with a story and someone to blame, and it’s a guy no one has ever heard of.”

Still undisclosed is the number of children who died during the time officers waited outside the classroom. Still unknown is the number of officers—local, state, and federal—who responded to the scene. Still unanswered by DPS and Border Patrol is what the army of agents and state troopers that saturate the area are doing, and what they were doing during the hour when children called for help.

Left to the state to police itself, we may never know. And the federal government, which easily spends billions of dollars to police South Texas, must now prove it is willing to answer to South Texas.