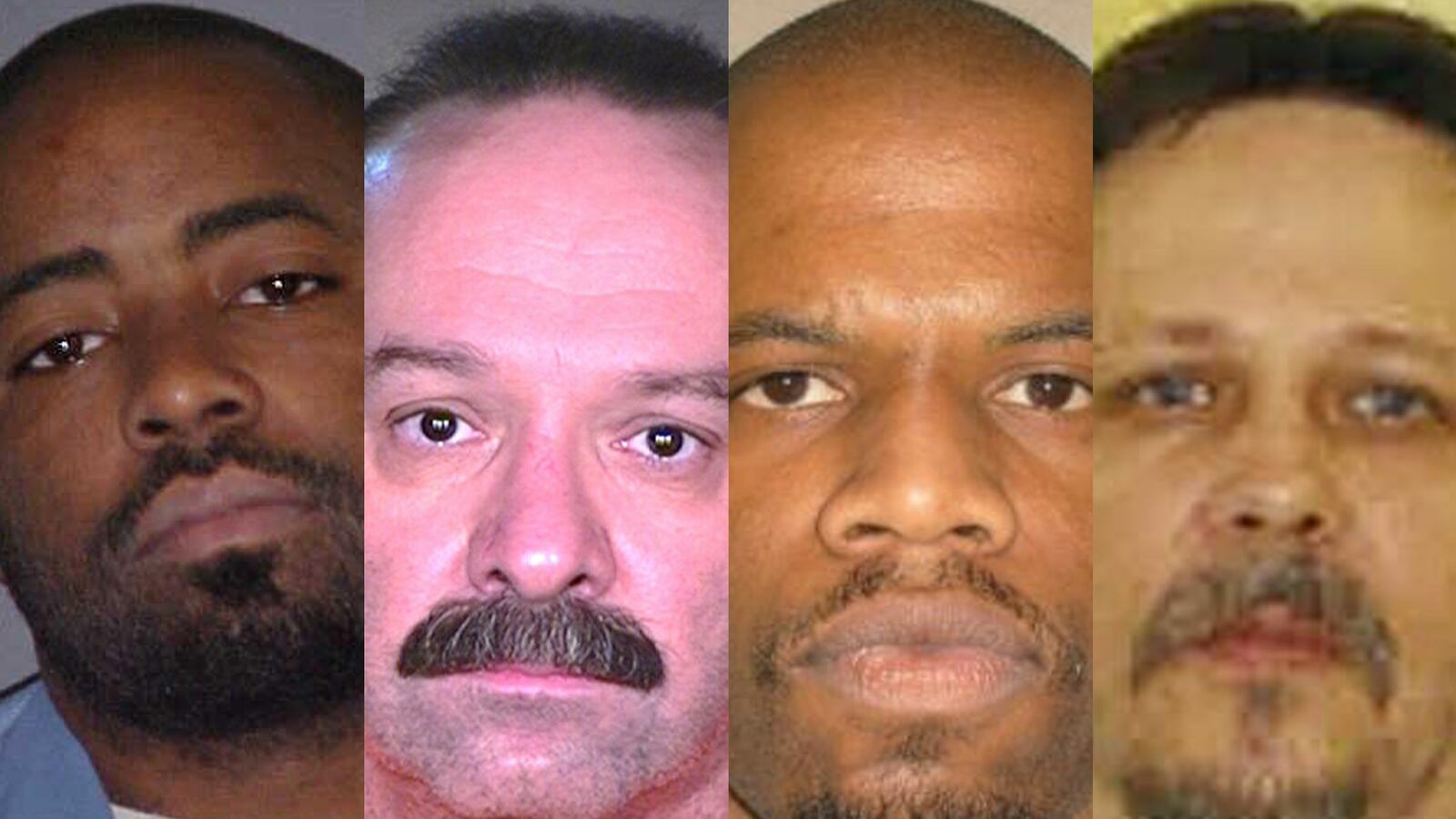

Another week, another botched killing under the legal euphemism of capital punishment. After macabre screw-ups in Oklahoma and Ohio, it was Arizona's turn last week, when double-murderer Joseph Rudolph Wood III took about two hours to die. The specific problem this time around was an apparently unreliable “cocktail” of the drugs used in the lethal injection process.

But let’s face it: There’s no good way to kill a person, even one as completely unsympathetic as Wood (he killed his ex-girlfriend and her father, shooting them at point-blank range). As a libertarian, I’m not surprised that the state is so incompetent that it can’t even kill people efficiently. But I’m far more outraged by the idea that anyone anywhere seriously thinks the death penalty passes for good politics or sane policy. It’s expensive, ineffective, and most of all, deeply offensive to ideals of truly limited government.

Consider that between 1980 and 2012, California spent $4 billion administering death penalty cases while actually executing just 13 individuals, according to a study produced by Loyola Marymount Law Professor Paula Mitchell. What’s more, Mitchell told Reason TV’s Tracy Oppenheimer, when the death penalty is in play, “the legal costs [per case] skyrocket to an extra $134 million per year, well above the cost to implement life without possibility of parole.” Given the severity and finality of the punishment, it makes all the sense in the world to make sure due process was followed in all death penalty cases. I’m sure death costs more in California (everything else does) than in other states, but there’s just never going to be a way to make it less than a huge waste of taxpayer money. And there’s no question that innocent people end up Death Row. The Innocence Project has documented that at least 18 innocent people, who served a combined 229 years in prison before being exonerated, have been saved from possible execution over the past 15 years.

Well, maybe you can’t put a price tag on the law and order that is instilled by the death penalty, right? A 2009 study by University of Colorado scholars published in the Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology concludes flatly “the consensus among criminologists is that the death penalty does not add any significant deterrent effect above that of long-term imprisonment.” It’s not even close, actually, with fully 88 percent of criminal-justice experts responding to a poll saying the death penalty does not act as a deterrent of murder, a percentage that was up slightly from a similar 1996 survey of scholars and law-enforcement analysts. Michael L. Ladelet and Traci L. Lacock also show how minor tweaks to assumptions embedded in studies that claim to show deterrent effects radically alter the results.

Part of the reason is that so few executions take place in a given year. Since the Supreme Court re-allowed executions in 1976, about 1,400 people have been executed (and never more than 100 in a given year), which is just too small a sample from which to draw definitive proof. However, the murder rate per 100,000 residents in non-death-penalty states has been consistently lower than the rate in states with executions.

That’s because the vast majority of murders aren’t planned-out crimes of the century or CSI-style serial killings, but opportunistic tragedies fueled by drugs, booze, and mental illness. “The threat of execution at some future date is unlikely to enter the minds of those acting under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol, those who are in the grip of fear or rage, those who are panicking while committing another crime (such as a robbery), or those who suffer from mental illness or mental retardation and do not fully understand the gravity of their crime,” explains Amnesty International.

So the death penalty wastes money, has no effect on murder rates, and is sometimes tossed at innocent people. Those three reasons are more than enough to end it once and for all.

Here’s one more that would hold true even if through some miracle the government could make the finances work, guarantee absolute accuracy in convicting only guilty perps, and show that executions significantly deterred crime: The state’s first role—and arguably its only one—is protecting the lives and property of its citizens. In everything it does—from collecting taxes to seizing property for public works to incentivizing “good” behaviors and habits—it should use the least violence or coercion possible. No matter how despicable murderers can be, the state can make sure we’re safe by locking them up behind bars for the rest of their—and our—lives. That’s not only a cheaper answer than state-sanctioned murder, it’s a more moral one, too.