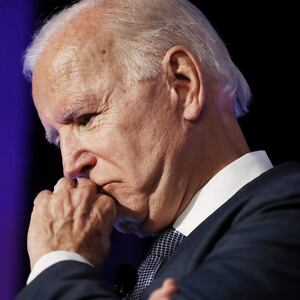

It’s one thing to preach unity, another to make it happen. Joe Biden needs Mitch McConnell the way the Earth needs the sun if he is to accomplish anything in the most closely divided Congress in memory. A Senate that is evenly split 50-50, with Vice President Kamala Harris’ vote needed to break a tie, and a three-seat margin in the House create powerful incentives for Republican leaders to stall Biden’s agenda and play for the midterms two years from now.

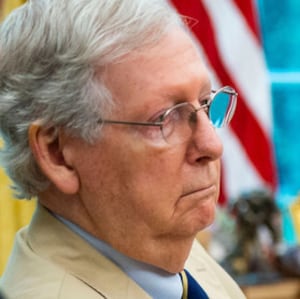

The wiliest protagonist in this game of thrones is Mitch McConnell, adjusting to his new status as minority leader while having to figure out what he and his party do about Donald Trump, a disgraced ex-president with a cult-like following, and a media infrastructure that disseminated little lies that congealed into the big lie that the election was stolen.

As Senate leaders struggle to implement a power-sharing agreement, McConnell is threatening to block any agreement unless Democrats agree to preserve the filibuster, an early indication of how he can muck up the works. If Biden is to achieve the agenda he campaigned on, he needs some buy-in from the colleague he has known and worked with since McConnell was first elected to the Senate in 1984. During the eight years Biden served as vice president, he was the one charged with handling McConnell and crafting last-minute deals that helped Obama fulfill his legislative agenda while avoiding a government shutdown.

Biden has cultivated his reputation as the McConnell whisperer, and now that rep is about to be tested. It won’t be easy but there is the hope that these two longtime denizens of the Senate can make democracy work and deliver for the American people. The events of Jan. 6 shook McConnell, forcing a recognition of what his president and his party had wrought in turning an armed citizenry against its government, and perhaps pushing him to take Biden’s outreached hand.

There is hope that Biden, a man tempered by time and tragedy, will get Republican help to stand up a vaccine program, pass COVID relief and propose legislation to meet the nation’s broader goals on immigration and infrastructure and energy policy. If so, the late Senator John McCain will be smiling. He went to his death bed calling for a return to “regular order.”

But when I turned to two longtime advocates of bipartisan politics, Matt Bennett with Third Way, a moderate Democratic group, and Bill Galston, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who helped found No Labels, a group that seeks to lessen partisanship, each of them warned: not so fast.

Bennett cautioned against thinking that the many years Biden and McConnell have known each other, and the respect and friendship that flows from that, would have any real bearing on whether and to what extent McConnell decides to cooperate with Biden, or not. “The question is not does he like Biden more than Obama—he probably does—but what does he want?” says Bennett. McConnell is juggling a lot of competing priorities. He has to figure out what to do about Trump, how to break with him if that’s what he decides is best for his party, and what the cost of that break would be in terms of primary challenges. He has to decide how to deal with the treasonous behavior by Senators Cruz and Hawley and four others in his caucus who voted to overturn the election results even after the Jan. 6 insurrection.

And most important for Democrats, McConnell has to decide which way forward to 2022 would most likely regain his Republican majority. Whether that’s to cooperate with Biden at least initially, or to stall and stonewall, no one knows the answer right now, probably not even McConnell. “McConnell shows no interest in legislating for the good of the country,” says Bennett. “He legislates for the good of his own politics. It’s very dangerous and bad, but that’s where we are.”

Bill Galston points to a short speech McConnell gave on the Senate floor Tuesday, the day before the inauguration. It was just two minutes and 34 seconds, but in that short time he said what no other Republican leader had been willing to say, at least not publicly. He said the mob that ransacked the Capitol had been “fed lies” and that Trump had “provoked” the incident. “I’m beginning to think McConnell could vote to convict if he means what he said on the floor,” Galston says. “I don’t think McConnell will do anything out of the goodness of his heart, but if his objective assessment is that it is in the interest of his party to head away from Trump resistance and move to getting something done, he will move.”

McConnell was sending a signal to Republicans, creating a “permission structure” for those who are weighing the cost-benefit ratio of stepping away from Trump while he remains the most popular Republican figure. With a Senate trial looming, McConnell has lots of calculations to make, the most central being whether he cooperates with Biden—and by extension responds to the urgent needs of the country.

The consensus is that this wiliest of politicians can’t be counted on to put the country ahead of parochial and political interests. President Obama in his memoir describes the coldly calculating and dispassionate McConnell as a most unlikely Republican leader.:

“He showed no aptitude for schmoozing, backslapping or rousing oratory. As far as anyone could tell, he had no close friends even in his own caucus, nor did he appear to have any strong convictions beyond an almost religious opposition to any version of campaign finance reform. Joe told me of one run-in he’d had on the Senate floor after the Republican leader blocked a bill Joe was sponsoring, when Joe tried to explain the bill’s merits. McConnell raised his hand like a traffic cop and said, ‘you must be under the mistaken impression that I care.’ But what McConnell lacked in charisma or interest in policy, he more than made up for in discipline, shrewdness and shamelessness, all of which he employed in the single-minded and dispassionate pursuit of power.”

Obama famously joked at the 2013 White House Correspondents’ Dinner about criticism that he hadn’t tried to cultivate McConnell. To those who suggest he get a drink with the GOP leader, Obama replied: “Really? Why don’t you get a drink with Mitch McConnell?”

Biden’s invitation to McConnell to attend church with him on the morning of Inauguration Day, in stark contrast to Obama’s aloofness, is the kind of gesture that comes naturally to the new president. He operates on traditions that are in his DNA from more than three decades in the Senate where the clubbiness of the world’s greatest deliberative body could override partisan passions for the right sweetener and even sometimes for the greater interests of the country.

We will soon learn how far senatorial courtesy goes and if Biden is under the mistaken impression that McConnell cares.