In some ways, the last remaining detainees are the worst of the worst.

At the beginning of Barack Obama’s presidency, the U.S. military began arranging for some 10,000 American-held detainees in Iraq to be freed or sent to Iraq’s justice system. At the end of that process a little more than 100 such prisoners have remained locked up because they are considered particularly dangerous.

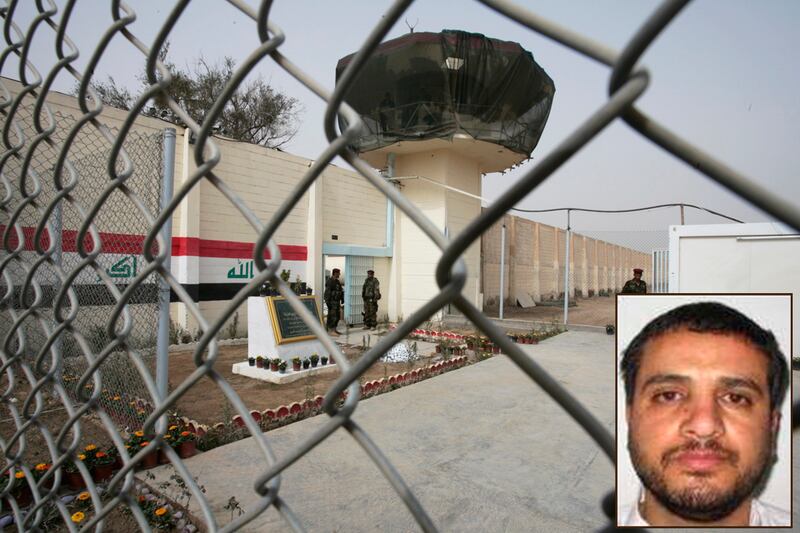

One such prisoner is a senior Hizbullah operations planner named Ali Musa Daqduq. In March 2007, U.S. special-operations forces captured Daqduq and he was taken into U.S. custody, where he remains to this day. U.S. military spokesmen in 2007 said Daqduq hatched the plot that killed five American soldiers in Karbala by dressing operatives in fake U.S. Army uniforms.

In less than two months, there is a good chance Daqduq will be handed over to Iraqi authorities, and even Defense Secretary Leon Panetta concedes he will not likely be tried in Iraq.

“We have made our concerns known to the Iraqis about the importance of detaining that individual but others as well,” Panetta said Tuesday at a Senate hearing on Iraq.

Asked whether Daqduq would face justice in the Iraqi court system, Panetta said, “I think he would certainly find better justice here.”

Daqduq and the other detainees in Iraq illustrate two of the thorniest problems for the White House as it seeks to wage a stealthy global war on terror while winding down ground-troop wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. First, without a status-of-forces agreement between the United States and Iraq, the U.S. military will have to try Daqduq or hand him over to the Iraqis when it leaves. An agreement to keep troops in place past December has been elusive for months.

Marisa Sullivan, deputy director of the Institute for the Study of War, an independent think tank with close ties to U.S. military leadership, said handing Daqduq over to the Iraqis would almost certainly result in his release.

“The biggest priority is getting him out of Iraq,” she said. “Turning him over to the Iraqis means he will be released. Given the realities politically in Iraq and the judicial system, it would cause too many problems for the Maliki government with Iran if they were to hold onto Daqduq.”

At the same time, the United States cannot continue to hold Daqduq indefinitely, particularly if the war ends at the end of the calendar year. The conclusion of the Iraq War is, in essence, the end of the U.S. authority to detain Daqduq and any other detainees in U.S. custody who are not members of al Qaeda.

The law that gives the U.S. military the authority to detain suspected terrorists captured all over the world, known as the Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF), applies to the war against al Qaeda and its affiliates.

While courts have stretched the definition of combatants to include affiliated groups like the Pakistani Taliban, Daqduq—who is a member of a militia based in Lebanon that is supported by Iran, and who was captured in Iraq—would not meet the criteria spelled out in the AUMF.

Robert Chesney, a law professor who specializes in national-security issues at the University of Texas, Austin, said Daqduq is “the worst of the worst in my opinion, but he is also the hardest of the hard cases because we don’t have a basis to detain him without a criminal charge going forward, in contrast to al Qaeda members.”

The Justice Department had, as recently as this spring, tried to make arrangements to try Daqduq in a civilian court in the United States for the murder of the five soldiers at Karbala. But it’s unclear whether he will be sent to the United States for trial or handed over to the Iraqis, according to U.S. government officials.

The White House has yet to decide the fate of Daqduq and the more than 100 other detainees still in U.S. custody in Iraq. Chesney said the domestic politics at the moment make a trial for Daqduq unlikely.

“A military commission makes the most sense in this case,” he said. “But the right is adamantly opposed to hosting a military commission in the United States, and the left is equally opposed to having anyone new brought to Guantánamo.”