Joe and I are walking along the ridge of Kayford Mountain in southern West Virginia with Larry Gibson. Small wooden shacks and campers, including Gibson’s simple wood cabin, dot the line of ridge where he and his extended family have lived for more than 230 years. Coal companies are blasting hundreds of thousands of acres of the Appalachians into mounds of debris and rubble to unearth seams of coal. Gibson has preserved 50 acres from the destruction. His forested ribbon of land is surrounded by a sea of gray rock, pale patches of thin grass, and barren plateaus where mountain peaks and towering pines once stood. Valleys and creeks, including the old swimming hole Gibson used as a boy, are buried under mining waste. The wells, including his own, are dry and the aquifers below the mountain poisoned. The fine grit of coal dust in the air settles on our lips and leaves a metallic taste in our mouths. Gibson’s thin strip of trees and undergrowth is a reminder of what has been destroyed and will never be reclaimed.

Gibson, 65, stands five feet tall. He is wearing a straw hat and overalls, has a moustache, and usually walks his property with a loaded Glock .45 pistol. He left his pistol today in his tiny cabin, where he gets his electricity from solar panels and a generator. We are headed down a dirt road with his lumbering, twelve-year-old black dog whose name, Gibson tells us, is “very complex. His name is Dog.” Loss of habitat has driven the remaining wildlife, including bears and wild boars, onto his property: “When I was a boy you didn’t see bears. You might see a paw print, but the coal companies done drove the bears in on us.” Larry Gibson was born on the mountain and spent his boyhood there.

There were once 60 families clustered around the mountain, along with a small general store and a church. Gibson’s father was a coal miner who had his leg shattered in 1956 in a mine collapse. The coal company did not pay any benefits. The bills piled up. The family sold its furniture. The house was seized, and for a few months Larry and his parents camped out under a willow tree. Gibson remembers that as a young boy he came upon his father during this time, a man who always seemed to him a tower of strength, sobbing.

The Gibsons—like the families of thousands of other coal miners, who in the 1950s could no longer find work as the mines were mechanized and diesel and oil replaced coal—were forced out of the mountains. They went to Cleveland, where Larry’s father found work in a barrel factory. He later worked for Ford. Gibson moved back to the mountain after he retired from General Motors on disability.

“Livin’ here as a boy I wasn’t any different than anybody else,” he says:

First time I knew I was poor was when I went to Cleveland and went to school. They taught me I was poor. I traded all this for a strip of green I saw when I was walkin’ the street. An’ I was poor? How ya gonna get a piece of green grass between the sidewalk and the street, and they gonna tell me I’m poor. I thought I was the luckiest kid in the world, with nature. I could walk through the forest. I could hear the animals. I could hear the woods talk to me. Everywhere I looked there was life. I could pick my own apples or cucumbers. I could eat the berries and pawpaws. I loved pawpaws. And the gooseberries. Now there is no life there. Only dust. I had a pigeon and when I’d come out of the house, no matter where I went he flew over my head or sat on my shoulder. I had a hawk I named Fred. I had a bobcat and a threelegged fox that got caught in a trap. I wouldn’t trade that childhood for all the fancy fire trucks and toys the other kids had. I didn’t see a TV till I was thirteen. Didn’t talk on a phone till I was fourteen. There was crawdads in the streams down at the bottom of the mountain. I could pick them out with my toes. Now nothing lives in the water. It stinks. Nothing lives on the land. And it’s irreversible. You can’t bring it back.

By the time he returned as a middle-aged man, the land of his boyhood was barely recognizable. His family’s 500 acres had shrunk to 50. Coal companies, whose old claims to mineral rights underground, many of them deeded by ancestors who could not read or write, gave them right to seize the land. The spine of the Appalachian Mountains is being obliterated to gouge out the seams of black coal. The constant, daily explosions at the edge of his property— which in one typical week in West Virginia equals the cumulative power of the blast over Hiroshima—rains showers of rocks down on his property. We walk among the graves of his family cemetery on the crest of the hill. Coal operatives in the late 1980s stole more than 120 headstones in an effort to erase the face of the cemetery and open it up for mining. These vandalized grave sites are now marked by simple wooden crosses. We stop at the grave for Larry’s brother Billie, who died in 2004. His stone reads: “Back to the Mountains for which you loved and eternal peace that had eluded you.”

“Buddy, when they was blastin’ out here, for instance, when they was this close to me, they was blowin’ rocks as big as basketballs,” Gibson says. “Me and my uncle got caught in a dynamite blast four different times on this place, not on their place, on our place. It was fly rock. It was like Star Wars, where you see all them rocks comin’ at ya in the movie. Well, this wasn’t a movie.”

He was able to save the cemetery near his house but watched helplessly in 2007 as bulldozers demolished an adjacent cemetery that also held family remains.

“They pushed 139 graves over a high wall,” he says:

They left us 11 graves. It was Massey Coal. The graves are now surrounded by their property. It didn’t belong to them. It belonged to my uncle, his grandfather, my great-great-grandfather. The cemetery was 300 years old, but there was coal underneath. I always tell people, “Ya got to stay cool, ya got to stay calm, got to be responsible, reliable, credible.” I was givin’ a tour and lookin’ across this valley when I seen this ’dozer goin’ through my cemetery. I was jus’ ’bout on my way back home to git one of my guns. An’ I’m a very good shot. This is what they do in the coalfields. They do what they want, and then they go fight it in court because they got the money and the attorneys and the time to do it.

He laments that in many of the grave sites there are probably no longer any caskets or bodies. The underground mining, begun more than a century ago, has created vast honeycombs beneath the earth that open huge fissures in the land, causing many of the graves to sink into the deep depressions. The wide cracks and gaping holes that dot the landscape mark the earth collapsing in on itself. Some of the cracks, three or four feet wide, run through the graves in family cemeteries. You look into the pit and see a deep, empty hole.

But Gibson refused to yield. He formed a nonprofit foundation in 1992 to protect the property. He has steadfastly refused to sell it to coal companies, although there are probably, he estimates, hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of coal beneath his feet. The relentless stripping of the forests, the vast impoundments filled with billions of gallons of toxic coal waste known as slurry, and the steady flight by residents whose nerves and health are shattered, has left Gibson one of the few survivors.

“There was one thing I was taught as a boy livin’ in the coalfields,” he says, “and that was bein’ organized. We didn’t know who the United States president was, but we knew the United Mine Workers president. We had learned to always fight back.”

His defiance has come with a cost. Coal companies are the only employers left in southern West Virginia, one of the worst pockets of poverty in the nation, and the desperate scramble for the few remaining jobs has allowed the companies to portray rebels such as Gibson as enemies of not only Big Coal but also the jobs it provides. Gibson’s cabin has been burned down. Two of his dogs have been shot and Dog was hung, although he was saved before he choked to death. Trucks have tried to run him off the road. He has endured drive-by shootings, and a couple of weeks before we visited, his Porta-Johns were overturned. A camper he once lived in was shot up. He lost his water in 2001 when the blasting dropped the water table. He has reinforced his cabin door with six inches of wood to keep it from being kicked in by intruders. The door weighs 500 pounds and has wheels at the base to open and close it. A black bullet-proof vest hangs near the entrance on the wall, although he admits he has never put it on. He keeps stacks of dead birds in his freezer that choked to death on the foul air, hoping that someday someone might investigate why birds in this part of the state routinely fall out of the sky. Roughly 100 bird species have disappeared.

“By the way,” he says, arching his eyebrows:

“y’all bin talkin’ to me fer an hour now, and y’all ain’t never asked me my opinion on coal. I’m against coal. I think coal should be abolished, ’cause the science is in. Ther’ been test after test after test ’bout the coal an’ related disease that kills people. Coal-related disease that kills people who never worked in the mines. We lose 4,500 people every year who never worked in a mine except they live in the coalfields. Mostly a lot of them is women, a high percentage of them is women, because women’s tolerance against coal dust is lower than men’s. Now, you have this here black lung, which affects 500 men a year. And then we have the emissions code. You heard about the World Trade Center terrorists? You heard about them? Bombing, three thousand people dying, but have you heard that with the emissions of coal we lose twenty-four thousand people a year in this country? You know, eight times bigger than the World Trade Center. Nobody say anything about that. Then you have the something like 640,000 premature births and birth defects, newborns, every year, every year, and nobody’s doin’ anything about that. Coal kills, everybody knows coal kills. But, you know, profit.

“They passed laws that ya can’t go down in Charleston in certain places and smoke in public,” he says:

Think ’bout it. I’m allowed to breathe this air here. The people within the coalfields are allowed to breathe the same air I’m breathin’ because the profit margin is higher than the price of a man’s life. So long as we can make a profit, we can step over the bodies, and the man can breathe the poisoned air. Why do they pass all these health and safety laws ’bout smokin’ cigarettes in public places an’ they let the kids go to school beneath a 2.5 billion-gallon dam filled with mine waste 250 feet away from a preparation plant? As long as they’re makin’ a profit. But how do the people make a livin’ here? The people have become submissive jus’ like a woman who is abused and beaten. An’ they have a high degree of respect fer the people who are doin’ it to ’em.

“I expect to lose my life to it, I guess,” he says about his defiance. “I expect, somebody scared, you know, somebody who normally wouldn’t do anything wrong, seeing me up here by myself. Because of my belief and my stand. And the fact that they may lose a job. And they got a baby on the way and one at home. They may lose their job, and they had a couple beers that day maybe. You know. And they see me. I’m hit, I’m hit, you know. Scared people make dangerous people. They act without thinkin’. An’ the industry uses people like that.

“But if I stop fightin’ for it, they’ll take it,” he says. “Do you know what it’s like to hear a mountain get blowed up? A mountain is a live vessel, man; it’s life itself. You walk through the woods here and you’re gonna hear the critters moving, scampering around, that’s what a mountain is. Try to imagine what it would be like for a mountain when it’s getting blowed up, fifteen times a day, blowed up, every day, what that mountain must feel like as far as pain, as life.

“I’m not a highly-brained guy here,” he continues, “don’t have a lot of education. I just point at the common denominator of things: You screw up one thing, another is gonna fall, and if that falls something else is gonna fall, and how much more do we have to fall before we start saying, ‘Whoa, there’s something wrong here somewhere,’ you know?”

“See that red pole up there?” he says, as we move toward the far end of the ridge. “It’s a marker. From this corner across there, OK? What gets me about this is, my family owned this. And when I go up through here, I look at it as if I was walkin’ on what was my family’s before. They say it belongs to them now. An’ ’member I told you how they took it? I look at it as if it still belongs to me and my family. But now you are on coal company property. You can be subject to arrest. You like peanut butter and pork and beans? That’s what they serve ya in jail now. I’m pretty regular.”

We climb up an incline at the edge of Gibson’s property. At the top we see vast pits and rocky outcroppings where there once were mountains. Seams of coal run like black ribbons through sheer rock face. The wind whips across the barren slate flatlands. It leaves a metallic taste in our mouth. Idle earthmovers, diggers, and bulldozers lie scattered on the rock face before us. A few patches, sprayed with fertilizer and grass seed, are a faint green. In most spots the thin topsoil and grass, sprayed on by the coal companies as part of their reclamation of the land, have washed away, exposing the stone beneath. White drill marks dot the top of the rock. The company will soon drill down and blast away another eighty feet of stone on the ravaged peak before us to get to more coal seams. About a dozen men with heavy machinery can carry out this kind of mining. When coal companies had to dig underground, they would employ hundreds, and at times thousands, of miners to extract the same amount of coal.

Gibson points to a huge impoundment of toxic coal waste that lies behind a dam in the distance:

They are dynamiting within 200 feet of the face of that dam. It’s over a one-thousand-feet dam. They say when the dam breaks, seventeen miles away the sludge will be forty feet high comin’ at you. Ya must understand, now, mine waste per gallon weighs four times more than a gallon water. Ye’r’ lookin’ at a lot of waste over there, and a lot of heavy waste. It’s sittin’ at thirty-five feet above an abandoned mine shaft, too. So it’s gonna come out. One way or another it gonna come out. An’ them dynamitin’ within 200 feet of the face and vibratin’ the waste down below. In this part of the country we call it blowout—when the mouth opens up in the middle of a hill and shoots stuff out like a rifle. At the rate they’re talkin’ ’bout, it will kill people here.

“An’ what chance are these people gonna have?” he says, looking down to a cluster of houses in the “holler” below. The mountains lie so close together that houses and communities scratch out space tucked in hollows, long rows between them known locally as hollers: “Ya see how narrow these hollers are? We’re gonna lose a lot of people.

“When it comes right down to it, I been callin’ fer a revolution across this country fer a long time now,” Gibson says. “I think it was Thomas Jefferson said, I think it was ’im, who said we should have a revolution every twenty years to keep the country in check. We’ bin way overdue.”

“What would it look like?” I ask.

“It would be holdin’ the government in contempt,” he says. “It would be holdin’ the government to credibility and accountability. It would be holdin’ people accountable fer their actions. That’s all I’m askin’ fer. They come in here and tell me, ‘Larry, you have to be reliable, accountable, responsible, credible,’ all the things they tell me, everything they jus’ taught me, I jus’ told you now, they ain’t bin doin’. That’s all I’m askin’.

“They’re gonna destroy my state, and the government’s gonna give them the incentives to do it,” he says. “My grandchildren and great-grandchildren won’t have any heritage here. They won’t have any mountain culture here, ’cause they’re wipin’ it out. I had the best of time of my life not knowin’ I wasn’t rich or comfortable or wealthy. How could I enjoy myself outdoors if I wasn’t wealthy? Who measures wealth? How do you do it? All the energy we have, all the people they destroyed, all the fatalities on these mine sites, and they keep makin’ reference to this as cheap energy.”

“What keeps you going?” I ask.

“I’m right,” he says. “That’s all.”

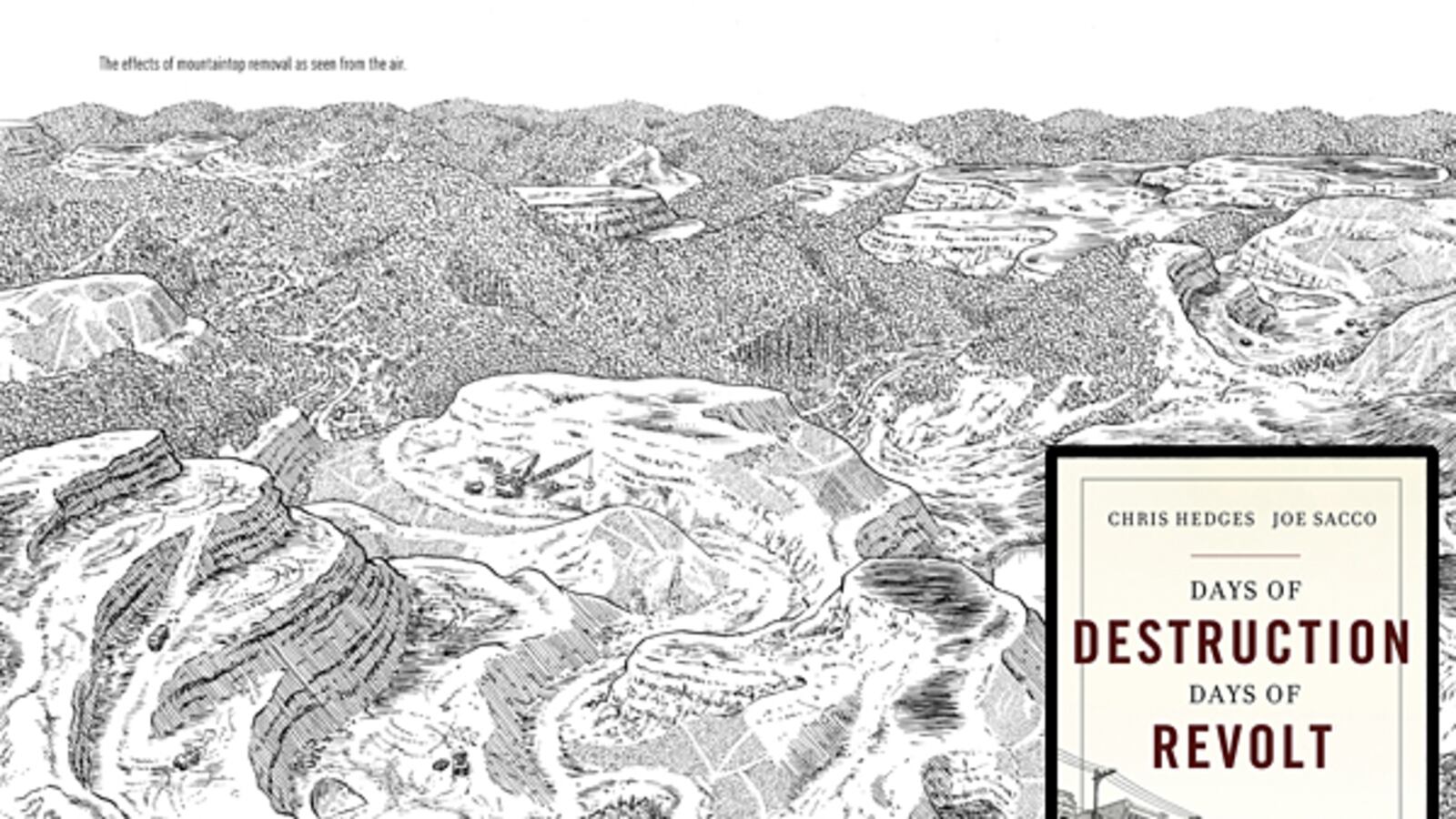

The next morning Joe and I are at Yeager Airport in Charleston, West Virginia, to fly over the coalfields with Vivian Stockman, the project coordinator for the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition, and Susan Lapis, a pilot and chemistry professor. The flight was arranged through SouthWings, a nonprofit group that flies observers across the Southeast to promote conservation. Stockman, who gets airsick when buffeted by the winds, has pressure-point wristbands and a patch on her neck to combat the nausea. We settle into the worn, black leather seats of Lapis’s 1977 Cessna 182 Skylane, which she calls the “station wagons of the air,” and put on earphones. We are parked next to a gray Air Force C-130 cargo plane. The Cessna rocks slightly in the gusts as we lift off from the concrete runway. We head south.

Lapis, as if she is patiently speaking to first-year chemistry students, explains what happens when heavy metals are blasted into the air. Enzymes, she says, depend on heavy metals. She tells us what happens when the balance is ripped apart by the release of calcium and magnesium into the atmosphere.

“When I was an organic chemistry student working in the lab, the way we would get a relatively insoluble substance to dissolve in a solvent was to grind it up with a mortar and pestle into a powder or little pieces. This increases the surface area of the substance to be dissolved, and thus makes it more readily soluble,” Lapis tells us through the headphones. “To harvest the coal in MTR [mountaintop removal], the layers of mountain in between the layers of coal are blasted to smithereens and dumped into valley fills. When rainwater trickles through this pulverized rock—more surface area—it can more easily dissolve minerals from the rock, some of which are heavy metals that are toxic in high concentrations. The metal ion-rich runoff from the valley fills then goes into streams, rivers, and groundwater of West Virginia in unnatural concentrations, sometimes toxic.

“From the air you can see weirdly-colored pools of water on the mine sites,” she says as we fly over an impoundment of coal slurry streaked with swirls of bright green, gray, and black, “colored by these metals in unnatural concentrations. Some people up in the hollows get foul-smelling, discolored water coming out of their wells or their kitchen spigots, and the coal companies are providing them with safe drinking water in huge containers. Some folks have to carry these giant jugs down the hill into the house for water to bathe the baby!”

Lapis explains that she could once move south by identifying landmarks from the air such as Williams Mountain, whose long, rocky outcrop resembled a battleship. But when we reach the mountain, we see only a denuded plateau of looping ring roads and gray rubble. She banks the plane so we can see down into another massive impoundment, filled with circles of bright green. “Heavy metal pollution,” she says as we fly over the dam. The coal ash in the slurry ponds, often the size of small lakes, contains high levels of arsenic, lead, cadmium, selenium, and mercury. Many of these waste ponds are perched perilously in mountainous crags above towns and even schools. When the dirt walls of the ponds burst, the damage is catastrophic.

We fly over hundreds of trees, which along with the topsoil and sandstone, are being bulldozed over the side of a mountain by seventy-five ton Caterpillar D10 bulldozers. Many of the trees lying like matchsticks on the sides of the peak are on fire. The gray smoke drifts upward.

“When we come back next month all the trees there will be gone,” Lapis says.

We see the thin layers of green that cling to the remaining rock face and the streaks where the sprayed-on grass seed has washed away.

“What are we thinking?” Lapis says softly.

As the plane dips over Clear Fork, we see, snaking through the trees, the old logging roads from the 1920s, when companies stripped southern West Virginia of its virgin forests. We fly over Brushy Fork Slurry Impoundment, the largest earthen dam in the Western Hemisphere, which was built above the Marsh Fork Elementary School, now closed because of the threat of a dam burst. Yellow construction vehicles crawl across the blasted moonscape.

“Your eye tricks you from up here,” Lapis says. “Those are some of the largest machines on earth. They have twelve-foot tires.”

She noses the plane toward a dragline excavator. Draglines, which cost upward of $100 million dollars and can be twenty stories tall, are the largest mobile equipment built on land. Bulldozers, container trucks, and backhoes, even the oversized versions we see below us, look like children’s toys next to the draglines. The draglines do the work of hundreds of miners. Half a century ago it took a miner a day to dig and haul sixteen tons of coal out of the ground. A loader, once a few hundred feet are blasted off the top of a mountain, can fill the back of a truck with sixty tons of bituminous coal rock in a few minutes. Jobs in the mining industry have fallen from a high of about 130,000 a few decades ago to about fourteen thousand workers. Once the unions were broken and the mines were mechanized, the coal companies began to strip-mine and then blast off the tops of mountains in a process known as mountaintop removal, or MTR, rather than mine underground. Most “miners” are, in fact, heavy machine operators.

The coal companies write the laws. They control local and state politicians. They destroy the water tables, suck billions of dollars’ worth of coal out of the state, and render hundreds of acres uninhabitable. The rights and health of those who live on the land are meaningless. The fossil-fuel industry’s dirty game of corporate politics was on display following the arrests in the fall of 2011 of 1,253 activists from the environmental group 350.org outside the White House. The protestors opposed the proposal to build the Keystone XL pipeline, which would have brought some of the dirtiest energy on the planet from the tar sands in Canada through the United States to the Gulf Coast. James Hansen, NASA’s leading climate scientist, has said that the building of the pipeline would mean “game over for the climate.” President Barack Obama, ducking the issue, said he would review the proposal and make a decision after the November 2012 presidential election.

The U.S. House of Representatives, urged on by lobbyists, however, voted a few days later 234 to 194 to force a quicker review of the pipeline. The House attached its demand to a bill proposing a popular payroll tax cut. Oil Change International calculated that the 234 Congressional representatives who voted in favor of the measure received $42 million in campaign contributions from the fossil-fuel industry. The 194 representatives who opposed it received $8 million. Speaker of the House John Boehner, a champion of the pipeline, has received a total of $1,111,080 in campaign contributions from the fossil-fuel industry. His counterpart in the Senate, Mitch McConnell, who pushed it through the Senate, has received $1,277,208. Obama, saying the Republican deadline left no time to approve the project, did not sign off on the pipeline. But his administration did not reject it, either. The president invited the company building the pipeline, TransCanada Corporation, to reapply, which it has done. Obama’s move pushed a final decision on the pipeline into 2013, beyond the presidential elections.

Elected officials at the state and federal level are paid employees of the corporate state. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the front group for the major corporations in the country, including Bank of America, Goldman Sachs, Chevron, and News Corp, spent more money on the 2010 elections than the Republican and Democratic National Committees combined. A staggering ninety-four percent of the Chamber’s contributions went to politicians who deny the existence of climate change.

Disease in the coalfields is rampant. The coal ash deposits have heavy concentrations of hexavalent chromium, a carcinogen. Cancer, like black lung disease, is an epidemic. Kidney stones are so common that in some communities nearly all the residents have had their gallbladders removed. More than half a million acres, or 800 square miles, of the Appalachians have been destroyed. More than 500 mountain peaks are gone, along with an estimated one thousand miles of streams, which provide most of the headstreams for the eastern United States.

The spine of the Appalachian Mountains, a range older than the Himalayas, winds its way through Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia. Isolated, lonely patches of verdant hills and forests now lie in the midst of huge gray plateaus, massive, dark-eyed craters, and sprawling, earthen-banked dams filled with billions of gallons of coal slurry. Gigantic slag heaps, the residue of decades of mining operations, lie idle, periodically catching fire and belching oily plumes of smoke and an acrid stench. The coal companies have turned perhaps half a million acres in West Virginia and another half million in Kentucky, once some of the most beautiful land in the country, along with hundreds of towering peaks, into stunted mounds of rubble. It was impossible to grasp the level of destruction in the war in Bosnia until you got in a helicopter and flew over the landscape, seeing village after village dynamited by advancing Serb forces into rubble. The same scale of destruction, and the same problem in picturing its true extent, holds true for West Virginia and Kentucky.

That destruction, like the pillaging of natural resources in the ancient Mesopotamian, Roman, and Mayan empires, is one of willful if not always conscious self-annihilation. The dependence on coal, which supplies the energy for half of the nation’s electricity, means that its extraction, as supplies diminish, becomes ever more ruthless. The Appalachian region provides most of the country’s coal, its production dwarfed only by that of Wyoming’s Powder River Basin.5 We extract 100 tons of coal from the earth every two seconds in the United States, and about seventy percent of that coal comes from strip mines and mountaintop removal, which began in 1970.

Those who carry out this pillage probably believe they can outrun their own destructiveness. They think that their wealth, privilege, and gated communities will save them. Or maybe they do not think about the future at all. But the death they have unleashed, the relentless contamination of air, soil, and water, the physical collapse of communities, and the eventual exhaustion of coal and fossil fuels themselves, will not spare them. They, too, will succumb to the poisoning of nature; the climate dislocations and freak weather caused by global warming; the spread of new, deadly viruses; and the food riots and huge migrations that will begin as the desperate flee from flooded or drought-stricken pockets of the earth. The steady plundering of the natural world, the failure to heed the warning signs of the planet, will teach us a lesson about the danger of hubris. The health of the land and the purity of water is the final measurement of whether any society is sustainable. “A culture,” the poet W.H. Auden observed, “is no better than its woods.”