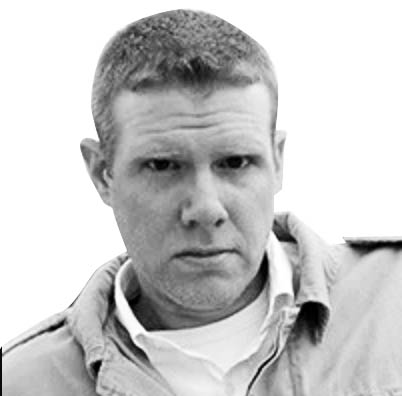

To read these remembrances of legendary journalist Christopher Dickey, written by The Daily Beast’s longtime correspondents and staffers, is to witness a master-class in the art of editing and reporting. We hope that through their words, Chris’ memory will continue to inspire a whole new generation of journalists to take up his example, to venture forth and cover the great events that shape their time on this planet, and to report back to the rest of us with stories simply and beautifully told.

Anna Nemtsova

“I’m your editor now.”

It’s not often a reporter gets a call from an editor just to ask how they are doing. That was the first call I got from Chris Dickey. In February, 2014, Independence Square in Kyiv was covered in flowers, candles and memorials. People were walking about, crying over the deaths of protesters gunned down a few days before. I was covering the uprising. Chris asked if I was OK. Then he said, “I’m your editor now. Try to keep a diary of little details. Describe smells.” I immediately knew I was in good hands.

The decade I spent with Newsweek, the last few years a chaos of failing ideas about what to do, was history. I now had a dream foreign editor. We worked on projects from 23 countries. Chris edited my copy every week for six and a half years. Every time he wrote “go” to a pitch or “great stuff” to a story, my wings grew. I am sure all of my colleagues felt the same.

Chris made sure I checked in often during the war in Donbas, made sure I was safe, told me to write first-person accounts. I only later realized that writing was the cure for seeing the trauma all about. He adored editing my tribute for the poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, often spoke about his own father’s poetry, and asked me about the song lyrics my father wrote.

I was lucky to spend a few days with Chris in Ukraine, showing him around Kyiv, introducing him to journalists and local intellectuals. His stories on that trip about reporting in San Salvador and the Middle East were priceless. I only wish I took notes.

Chris taught me to sum up heaps of reporting in a simple idea and feel strong about my own understanding of a story: “Say what you really want to say,” he advised me. There was a vibe around Chris that made you want to rush back to your laptop and write. Dozens of people now say Chris was a mentor for them. How could he manage to report his own, powerful stories, write seven brilliant books, edit our copy and bring up a large generation of journalists all at the same time? Our world is less brilliant without Chris in it. I hope with time, and in his memory, we all learn to be more patient, kind, attentive, graceful and elegant.

Chris wrote me an email on his last night. It was in response to a pitch. It said: “Pursue your reporting, file what you know, when you know it.” I will do exactly as he said.

Anna Nemtsova is a correspondent for The Daily Beast based in Moscow. Her work has also appeared in The Washington Post, Politico, PRI, Foreign Policy, nbcnews.com, Marie Claire, and The Guardian. She is the winner of the 2012 Persephone Miel Fellowship and a 2015 recipient of the prestigious IWMF Courage in Journalism award.

Michael Weiss

The first time I met Chris, in a greasy spoon diner about a block away from The Daily Beast's offices in Chelsea, he told me a story about his time in Iraq. He'd been sent by Newsweek to cover the early days of the U.S.-led invasion in 2003 and he was onto a major scoop. How was it, he asked, that everyone who turned up to Paul Bremer's interminable press conferences did so covered in a thick film of dust and sand and grime, no matter how hard they tried to keep their attire clean—everyone, of course, except for Paul Bremer. The leader of the Coalition Provisional Authority was always tricked out in pristine and pressed suits and so surely there must have been a functioning dry cleaner somewhere in occupied Baghdad. Chris investigated and Chris hit paydirt. Bremer, he archly informed me, had been sending his clothes out to be laundered in next-door Jordan, all while touting the virtues of nation-building and democracy-installation at the end of a bayonet in Mesopotamia. Well, it may not have been Pulitzer-worthy stuff, but it was an unmistakable portent of how things would fare in that war, one of many Chris covered over a remarkable 40-year career.

The last time I spoke to Chris (and here I mean the old-school form of speaking—a proper chat on the telephone, not a text message or email) he recited whole swaths of "A Shropshire Lad" word-perfect from memory. I'd told him I'd been working on a lengthy essay about A.E. Housman, a poet who I found uncannily captured our era of ‘social distancing’ better than others. Without any further prompting out poured lines now even more obscure than "blue remembered hills" or "When I was One-and-Twenty." Owing to who his father was, Chris naturally grew up steeped in verse and prose. But he was also of a generation and cut of American journalist—I always thought of him as the Murray Kempton of Parisian exile—which found merit in rote memorization and which could start an essay on, say, a grisly al Qaeda bombing by quoting from Eliot or Auden. Now here's another indelible memory of my dear friend and mentor: The Daily Beast’s Foreign Affairs Editor had several of Auden's poems taped to his seldom-visited office in New York. Earth, receive an honoured guest: Christopher Dickey is laid to rest.

Michael Weiss is the co-author of The New York Times bestseller ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror and of The Menace of Unreality: How Russia Weaponizes Information, Culture and Money. He lives in New York.

Nina Strochlic

Chris Dickey’s visits from his home in Paris to Daily Beast headquarters in New York made the newsroom sit up a little straighter. First, there was the wardrobe: Would he be wearing an elegantly tailored suit, with a corner of Hermès silk poking from the pocket? Or a hundred-pocket khaki vest, the kind favored by war correspondents in the 1980s?

Those were the two options, and whichever he chose stood out enviously against our jeans and sweatshirts. Chris was simultaneously the most glamorous and adventurous person who’d ever walked among us.

I don’t remember our first interactions, but at some point I made it known that I dreamed of following in his footsteps, of becoming a foreign correspondent who traversed the world telling stories, learning languages, covering historic moments—but how?

Then, a decade ago, and now, there are few answers to that question. Journalism had become a much different field than the one he’d entered four decades earlier as a correspondent for the Washington Post and then Newsweek. He’d adapted seamlessly, using blogs, TV, and every social media platform to tell stories. But he knew how hard it was to get a foot in, and so he graciously sat with me—and any young journalist—for hours, in his office, over lunch, at drinks, to offer advice and ideas. He seemed to have all the time in the world for us.

“What is a long lunch with Chris Dickey like?” a colleague messaged me one day. “He's so fucking prolific. He can write a new piece every day and write in his blog and go on tv and write a book in his down time.”

“I KNOW,” I responded.

“and seemingly knows EVERYTHING about EVERYTHING.”

“he literally knows everything about everything.”

When I began to get foreign assignments, I’d confer with Chris. No matter what the country, he’d already been there and observed both its bloodiest and most triumphant moments with his own eyes. On my way to the Democratic Republic of Congo, he told me about watching then-dictator Mobuto Sese Seko fall to the arriving armies of future dictator Laurent Kabila. He and another correspondent left their hotel in Kinshasa, rented a canoe, and rowed across the Congo River to the parallel capital: Brazzaville, in the Republic of Congo. They, naturally, opened a bottle of champagne for the ride.

When I received a grant to report on the Syrian refugee crisis in Jordan, Chris told me that when the former King Hussein felt like speaking to the press, he used to summon him from Paris on a private jet. Arriving to Amman, he’d be taken straight to have an audience with the ruler of the Hashemite Kingdom.

On my way back from an early assignment, I had just emerged from a border crossing when Chris sent a piece of advice via WhatsApp: “write down how everything smelled and sounded and tasted.” I told him I would, that I had thousands of photos stashed away as memories. Photos, he said, are limited. “A smell, a taste that is recognizable literally or intellectually has a completely different effect. I once rode into a war zone with Joan Didion in El Salvador…”

He paused there, clearly enjoying the drama.

“And there was a middle-aged Salvadoran woman just trying to get home. When Didion wrote about it she remembered the woman left the faint scent of Arpège in the taxi... There on the edge of the war. I did not notice. But I cannot forget the impression that one little observation left with me when I read it.”

He finished the tale with a clue: “Read her book Salvador and check the dedication.”

I did, and there was his name, of course. Chris covered the Salvadoran war in the 1980s, helping to reveal the existence of CIA-backed death squads that terrorized the country. More famously, in his spare time, he took the visiting Joan Didion on a grand tour.

By the time I first went to El Salvador, I was no longer working for The Daily Beast, but I conferred with Chris anyways. He’d interviewed and photographed the outspoken Archbishop Oscar Romero, who was murdered for his human-rights crusades, and canonized as a saint nearly 40 years later. He asked me for a T-shirt with Romero’s face on it, which were plentiful.

A few weeks ago I found a strange postcard at a thrift shop in Oregon. The image showed a giant puppet of Romero raised high above a crowd of worshippers in a field somewhere in the U.S. I hadn’t spoken to Chris in a year, but I sent it him with a rambling note, telling him I was learning the banjo and needed to finally watch the famous scene from his father’s film Deliverance, that I imagined quarantining in Paris was glorious, and that I hoped he’d be editing my stories again one day soon.

I don’t know if he ever got it, and I wish I could send many more. I'd write that his guidance was crucial to the success of a generation of reporters, that no one else has so fully embodied the ideals of journalism, that the way he lived his life—never scrimping on glamour and adventure—was inimitable, and that the world would lose some bit of its color without him.

Nina Strochlic is a writer at National Geographic. She is a former reporter and researcher for The Daily Beast.

Philip Obaji, Jr.

Chris mentored me and made me a better person. When I first began to contribute to The Daily Beast in 2015, I was far from being excellent. Chris gave me the opportunity to make mistakes, to learn, and to practice what was right. He made me feel very important and also made me a more confident person. I am honored to have met him. I just cannot believe he is no more. This is so heartbreaking. We were in touch hours before the sad news broke. Little did I know the words of appreciation he sent to me for an article I had filed were going to be the last I will get from him.

Chris, you meant so much to me. By giving me the opportunity to tell the most important stories out of Africa, you gave a chance for Africans to be heard. If you could look towards northeastern Nigeria, you will see the women and children in internally displaced persons camps who feel more secure where they live because you gave a chance for their stories to be told. I still remember the day you took time to share photographs and narrate the plight of the kidnapped Chibok schoolgirls because, as you told me, you wanted to draw more attention to their situation. That was who you were—a kind man that was always willing to help.

Chris, I will miss you and, as you always did for those you loved, will light a candle and say a prayer for your soul. Rest In Peace, my mentor!

Philip Obaji Jr. is the founder of 1 GAME, an advocacy and campaigning organization that fights for the right to education for disadvantaged children in Nigeria, especially in northeastern Nigeria, where Boko Haram forbids western education.

Nadette de Visser

Much has been said and written about Christopher Dickey’s impressive career as an author and journalist, about his travels throughout the world, about his oversight and insight and about his vision and wit. To me, Christopher embodied all of that and more.

I met Christopher in 2008 in Kuwait City, where we had both been invited to speak at a conference themed, “The influence of Western media on relations between East and West.” At the time I had just moved back to Amsterdam after five years of living and working in Israel and Palestine and Chris was the foreign editor of Newsweek. With a shared history in the Middle East there was an instant connection. We had lots to talk about and observations to share.

I remember one night, Kuwait's strict alcohol laws notwithstanding, when a black van with tinted windows pulled up and blocked our way at the restaurant where we, the speakers, were just about to leave. After some confusion—the thought of kidnapping did cross my mind—it became clear that this was an invitation to be whisked away to an unknown location, where alcohol would be flowing generously.

Being pregnant, I politely declined and rather than leaving me stranded on my own, in solidarity, Chris stayed with me. We ended up talking all evening. Endlessly fascinated, I would be listening to his stories from that moment onward. It would become the introduction to a friendship and working relationship that would grow stronger with each passing year.

Shortly after we had both returned home Chris first asked me if I was interested in writing for Newsweek. At first tentatively, I started writing under his careful, attentive guidance. Slowly but surely, Christopher became a formative presence in my work and life. His became one of those ‘voices’ that influence the ‘window’ through which you look at the world.

With every article I wrote, and with opinions I formed, he became an additional internal voice scrutinizing me, having me look at subjects from more angles, diverse perspectives, pointing out weak spots, until I ‘got it right.’ It was as if his voice was added to the system of neural pathways benchmarking key points to avoid or advance to.

Regularly, whenever there was a need or want, I could touch base, we would meet, mail, talk by phone or text, and Christopher would always be there, answering the call, always interested, curious, present. He would come through, be a safety net.

Maybe it was the kind of security that had somewhat lacked him as a child growing up, that prompted him, unwavering, to become a pillar to others. I felt lucky to be one of those souls in his orbit.

By the end of 2011 we interviewed Dutch populist politician Geert Wilders for Newsweek. The yearlong chase had, to our surprise, yielded results; he agreed to speak to us. It was at a time when the white-haired politician was doing extremely well in the polls. He was a powerful man. He hadn't been speaking to any of the Dutch press for over a year, so a certain impact was expected. On the train over to The Hague we discussed strategy. Chris said we shouldn’t attack him on his opinions, because that would be exactly what he expected and he would have his answers ready. There was nothing to gain there. If, however, we would have a friendly conversation, he might become off-guard.

Wilders’ secretary gave us 15 minutes to talk to him. But when she came in when our time was up, she was brushed aside by Wilders and the talk continued. Half an hour later Wilders, with some irritation, sent her out of the room yet again until, after 50 minutes, Christopher ended the interview saying we ‘had to catch a train.’

The Wilders story was a hit, discussed in all the Dutch major news outlets. Koos Breukel, the photographer who took the cover photo, mailed us a little memento of the day, to ‘hang in the Christmas tree.’ “Hah.” Chris wrote “You can see we were trying not to stand too close to him!”

Privately our friendship was growing too. My daughter Nuri was born in the year Christopher and I had met and she quickly became a little like an extra grandchild, at least in her experience. Family was paramount to Christopher. He adored his wife Carol and her mother Madeleine, his much younger sister Bronwen, his son James and his wife, and their children. They were all close to his heart and he and Carol effortlessly made my daughter feel like ‘part of the bunch.’

With the same ease that he had taken me under his wings at Newsweek, he took me along when it turned into Newsweek-The Daily Beast and again when he chose for The Daily Beast.

Throughout the years, sometimes a pang of dread would run through me as I imagined a world without Christopher in it. He worked too much, too hard, rarely pacing, never stopping. His drive was a force of nature not to be stopped, but I would wonder if his body could keep up with the pace of his inquisitive mind.

Imagining life without him meant looking at a life considerably dulled down, it was not a trail of thought I wanted to linger on.

Death for me personally never came as close as in the winter of 2014, when I caught pneumonia. Chris of course knew about it and kept in close touch. When I started to recover he wrote to me about the time his lungs caught fire. “I had pneumonia over Christmas 2003 and really have never experienced anything quite like it. That I was on vacation in Dubai with my son did not make it better at all. And that same winter a young woman I knew had flu-pneumonia and went into a coma, starting a chain of terrible events recorded in Joan Didion's two books Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights. The first one, by the way, you should read. It is one of the most beautiful yet realistic essays on death that I know.”

“Life changes fast, life changes in the instant,” Joan Didion wrote in The Year of Magical Thinking, “you sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends.” Since Chris died, life as I know it has ended.

I am putting these words to type in Calabria, southern Italy, where the skies are intensely blue, the earth is dry, yet abundant, and the waters are vast and deep. I try to grapple with Christopher’s sudden and absolute absence from this world. It is an enforced, blunt awareness that must inevitably set in soon. But I do not want to know it yet. The skies over Calabria are intensely blue. Goodbye, my dear friend.

Nadette De Visser, the author of Jeruzalem/Quds, writes from Amsterdam about issues of culture and conflict.

Itxu Díaz

Last Wednesday morning I received a notification on Instagram: “Chris Dickey liked your photo.” The veteran journalist had given a like to a picture I had taken on a beach in La Coruña, northwest Spain. I remembered then that I owed him an email. But I never got around to sending it. A few hours later, the sad news of his sudden death arrived from his home in Paris.

Every piece I did with Chris was a master’s degree in journalism. When the jihadist threat hit Europe, Chris would reach out to all of us correspondents together in long e-mail chains because he wanted the best information possible. He would try to translate my texts faithfully. He always made my articles better. Even when my ideological approach didn't match his, he was rigorously respectful in the translation, and subtly funny when I needed some of my silly thoughts redirected.

Two weeks ago I told him that the University of Barcelona had detected that the coronavirus was already circulating in the wastewater of this city more than a year ago. I proposed writing a piece about it for The Daily Beast. He said he didn't think it was a story for them right at the time. However, he added: “But I am interested in taking a look at the study, send me a link.” That was journalist Christopher Dickey. Even if he wasn't going to publish the story, he wanted to know first-hand from the source.

I admired everything about Chris. From his chronicles in The Daily Beast to his Instagram feed, where he also proved to be an excellent photographer with a special sensitivity for capturing the everyday soul of cities like Paris and New York. His style, rigorous and entertaining, discreetly ironic, and his way of directing and editing with character and freedom, has allowed the Beast to have during these years one of the best international sections in the world. The common note in all his activities was love. He loved journalism: telling something to someone, learning it, touching it, and feeling it, and then putting it in writing, or analyzing it as a television expert, on MSNBC, CNN or France 24.

He put this same passion into the reprint of the twilight poems by his father, renowned writer James Dickey. When I got a copy of Death, and the Day's Light, with a wonderful foreword by Chris, I better understood his sensitivity, passed from father to son: “Of a whole thing. Show me the sea, / Second son, for the one time: the one time. Of all. Real God, roll. Roll.”

“James Dickey composed huge, beautiful, and awe-inspiring images,” I wrote then in Diario Las Américas, “that shake the soul, the imagination, and wake us up from the tedium of summer, on these August afternoons, to understand the lives within our lives.” I now realize that you could feel this same thing when contemplating the work of Chris who, perhaps in a posthumous wink to his father’s poems, died on a sailor’s day, July 16, when the Catholic world celebrates the patron saint of the sea, Our Lady of Mount Carmel.

Shortly after his death, Twitter was flooded with beautiful messages. All of them highlighted Chris’ kindness. It's no cliché. He was essentially a kind man. One of those few people capable of making anyone who came into contact with him a better person. Journalist Tessa Miller recounted an anecdote that defines him well. In 2015, when she became ill and was admitted to the hospital, she received weekly photographs in her mail of the candles that Chris lit for her in churches around the world—a total of 37 candles!

I am convinced that the candles from those 37 churches will be now lighting his path to eternity.

Itxu Díaz is a Spanish journalist, political satirist, and author of nine books on topics as diverse as politics, music or smart appliances. He is a contributor to The Daily Beast, The American Spectator, The Daily Caller, National Review, The American Conservative, The Federalist, and Diario Las Américas in the United States, and a columnist for several Spanish magazines and newspapers. He was also an adviser to the Ministry for Education, Culture and Sports in Spain. Translated by Joel Dalmau.

Brendon Hong

I was introduced to Chris in December 2013. At the time, I had no idea that we would end up working on many texts covering China, Hong Kong, and occasionally other parts of Asia for the next six and a half years.

Chris always managed to bring a motivating energy to what can sometimes be pretty bleak work. He wanted to see history unfold up close as much as he could; and if he had to watch it from a different time zone, then he did all he could to hear from people who were there. How a place or event smelled, Chris told me more than once, makes people remember it deeply. And only people who were there can offer that description.

I will miss the marginalia that Chris and I shared when we worked on texts—trivia about dictators and statesmen, observations about art, masterful guidance that he would pack into just a few words but still give me plenty to ponder. All of this made dismal situations just a little less dismal. Manageable, even.

Chris was fascinated by how the phrase “give me liberty, or give me death” was used in 1989 during the Tiananmen protests in Beijing, and now in Hong Kong, giving the words renewed meaning more than two centuries after they were spoken in 1775 Virginia. One of the last things I did for him was commission a calligraphic interpretation of the quotation in Chinese. I managed to send the digital file to Chris a week before he died—and he loved it, I think. But the piece of brushwork is now resting on my shelf, unframed, its destination lost.

Brendon Hong is the pseudonym of a longtime contributor to The Daily Beast based in Hong Kong.

Tim Teeman

I loved working with Chris on stories, including in the week he died (which still seems so insane), because he not only knew his beat, he knew and had seen the world. The beat was him. You trusted him, and his correspondents trusted him. Chris was kind and meticulous, generous to all journalists and young journalists in particular, a mentor to so many. He wanted to help get stories on to the page. He wanted to showcase writers, and showcase the issues and narratives they—and he—felt so passionately about. He was an editor who was also a writer, and he loved and appreciated good writing—so, lucky you if you got to write for him.

Chris was also one of the most beautifully dressed journalists I have ever met, the archetypal foreign correspondent. The suits were fitted, the shirts were crisp, the ties perfectly knotted. After seeing you, you imagined Chris going to a swish restaurant or private members’ club to get the latest dish from a spy or diplomat. I always felt a total scruff when he was in the office. He was twinkling, funny, dry, and also authoritative. It was a consistent surprise to me that Chris wasn’t British because he seemed way more “British” than me, a Brit.

Chris also knew the importance, the moral importance, of what stories conveyed to the reader. He knew how precious and fragile the world was, which is why he felt so disgusted by despots and dictators (and he loved writing about them too). He had seen war, and terrible things. And, as his Instagram showed, he saw beauty everywhere. I think this is important: as ugly as the world could be, and as ugly as many of the stories he had to cover and edit from others, he appreciated everything that made the world sing—a beautiful building above the façade of a fast-food restaurant, individual lives and moments captured on the streets, gorgeous and unexpected fleeting moments.

I edited Chris’ 2018 Daily Beast piece, written after the death of actor Burt Reynolds, about Reynolds filming the movie Deliverance (1972), which was based on his father James Dickey’s 1970 novel. The movie has always fascinated me, and Chris had already written a memoir about his complex relationship with his father with a title that centered it (Summer of Deliverance: A Memoir of Father and Son, 1998). Here is that 2018 piece; its eye for detail and sensitivity, its revelations and observations, are, for me, 100 percent Chris.

Tim Teeman is a multi-award winning senior editor and writer at The Daily Beast and the author of In Bed With Gore Vidal: Hustlers, Hollywood and the Private World of an American Master. Before joining The Daily Beast, Tim was US Correspondent at The Times of London. Tim has won prestigious awards for his work from the Los Angeles Press Club, the New York Press Club, and from NLGJA (Association of LGBTQ Journalists).

Josephine Hüetlin

I first met Christopher Dickey virtually in 2016. I was living in Berlin and Chris gave me some of my first-ever journalism assignments, to report about Germany for The Daily Beast. For the next year, I’d be racing around and quoting his emails constantly, telling my flat mates that I “have to file asap,” that “the lawyer is going over it with his fine-toothed comb” and that it was imperative to “keep digging.” I was so excited. Being a freelance correspondent can be precarious and stressful but Chris made every job too fun to want to give it up. He was always adding some extra special stuff to a copy when he edited. Reading his comments on a draft often made me picture him smiling to himself as he typed out some devastating takedown, either of a protagonist or a blunder on my part. I’m very grateful to have gotten the chance to learn from him and so sad I never got to meet him in real life.

Josephine Hüetlin is a freelance correspondent based in Berlin.

Kim Dozier

Chris was a collector of aspiring talent. No would-be writer or reporter was too lowly for him to give his time, to give them a chance.

That’s how he came across to me as a brand new, broke stringer in Cairo, Egypt, circa 1992. I had a bare modicum of writing experience at a D.C. newsletter, and just enough Arabic to get by. He gave me the opportunity to file copy to Newsweek, which he honed into brilliant prose that he wove together from multiple foreign stringer dispatches.

And he gave me what I remember as my first official Newsweek/Washington Post assignment, to guide Lally Weymouth around Cairo for a couple days of interviews, in advance of Chris's arrival from Paris for the key Mubarak interview. And... I blew it.

I’d set up the interviews, but didn’t quite understand that I needed to secure an air-conditioned car with professional driver, befitting the status of a major news figure like the inimitable Lally Weymouth. Instead, I put Lally, in her Chanel suit with Prada heels or similar, in an un-air-conditioned, beat-up Cairo taxi at the height of Egypt’s blistering summer.

She bore it with good grace, even when I made her hop out of the taxi and dash across a busy two-lane highway and climb up the steeply sloped entrance road to the foreign ministry, in her immaculate suit and heels befitting her interview to come with the Foreign Minister.

I shared my error with Chris; he teased me gently about being too “REI” for my own good, and from Paris, he picked up the phone and called someone who knew someone (because he always knew someone in just about every country you could name), and he located an air-conditioned limo in Cairo. He quietly, gracefully smoothed it all out, thereby saving his mentee’s nascent foreign correspondent career.

The clips he helped me amass would help establish bona fides that helped build a lifelong career covering foreign policy. When I returned to print after several years with CBS News, Chris was my editor again at The Daily Beast, honing and tuning my stories again into tales that jumped off the page, while also setting the example for us all by penning his own richly reported, impassioned dispatches.

Forever grateful. Salute to you, Chris. We will miss you.

Kimberly Dozier is a TIME Magazine contributor and CNN Global Affairs analyst. She’s covered conflict across the Mideast and Europe, and national security policy in Washington, DC, since 1992, first as an award-winning CBS News correspondent and later as AP's intelligence writer.

Jake Adelstein

“If the greatest article in the world is printed out and dropped in the forest—it isn’t a great article. In order for something to be valued it has to be read—the interaction between reader and writer is the alchemy necessary for magic to happen. That’s important; you need what you write to be read by someone.

What's a good story? Don't ask yourself ‘Can I write this?’ Ask yourself, ‘Would I really, really want to read this?’ If it would be the first thing you'd go to on a crowded homepage, that's the story we want.”—Christopher Dickey, pontificating on writing in a Paris café in 2019

When we started using Google Docs at The Daily Beast, sometimes I would watch Chris editing our story with fear and awe. I could see his invisible hand moving words, crossing out sentences, moving paragraphs, adding comments and rarely were things not dramatically improved in the process. Sometimes the changes were so subtle, that I would never have noticed them if I didn’t watch them taking place.

I know that I will be haunted by Chris, but in a good way. I am always going to have his voice in my head. There are some people in your life who are like that, they never really die; they just aren’t here anymore.

I hear the voice of my best friend Michiel Brandt, like Jiminy Cricket, when I am on the edge of a murky ethical decision. I hear the voice of Detective Chiaki Sekiguchi when I am pushing for an answer or when I am contemplating backing away from something that seems too powerful to confront. And I realize that for the rest of my life, when I am editing myself, whether writing for The Daily Beast or another book, that I will hear the sonorous and crisp voice of Christopher Dickey, asking me, “What do you really want to say here?”

When I took my daughter to France for her 17th birthday, we had lunch with Chris and of course, we had wine. The interaction and banter between them was highly amusing—even more so because Chris treated her like an adult. And she liked that. Last year, I took my son to New York as well and we had brunch with Chris and The Daily Beast’s legendary and still deeply needed copy editor Lauren Hardie. Chris talked to everyone as an equal and he listened. This inspired trust and respect, even from teenagers. And Ray, who was 15, but already taller than me, said after we left, “He’s really cool.” From Ray, there are probably no greater words of praise.

I once spent six hours drinking and talking with Chris in a little bistro close to his house and felt like only an hour had passed. He told stories as well as he wrote. Not many people remember but Chris was one of the few journalists in America who warned the world that the intelligence on the Iraq War was baked and that the entire effort was going to be a clusterfuck. They didn’t make a movie like Shock and Awe about Chris, but I was shocked and awed to read his coverage for Newsweek. If the world had listened we could have avoided thousands of deaths and a trillion dollars of waste.

I never really had a mentor as a journalist in English. I spent the first 12 and half years of my reporting life writing in Japanese for a Japanese newspaper. I had some excellent teachers and still frequently see my editor from those days, who still talks to me like I am a well-meaning newbie who can write but probably should also be bringing him a cup of coffee on my way back from the canteen. It took me a while to get used to writing in The Daily Beast style. Chris was very patient, he wrote me once, “Writing in two different languages—especially languages THAT different—is to say the least disorienting. And it's not just the language. The style of journalism is very different. But you've been doing a great job and there's obviously a lot of hunger for news from your side of the globe. Your story was in the top five on the site yesterday. All the best, Chris”

Chris understood teamwork and the importance of camaraderie, in subtle ways that most people wouldn’t bother to care about. For nearly five years, my best friend Mari Yamamoto and I have written together for The Daily Beast. We sometimes joke in the still very sexist and xenophobic society that is Japan, that the two of us, one Japanese woman and one gaijin, put together equal one Japanese man. On complex stories, two heads are often better than one. The thing is it’s not always an equal task. Sometimes, Mari does the majority of the work and I’m just along for the ride and vice-versa. The thing is that Chris understood this and he would adjust the byline accordingly. Sometimes, he’d even check back with us. He could recognize our styles like they were fingerprints. “Tell Mari, this paragraph is powerful and punchy.”

It’s a little thing. Probably the only people in the world who notice are Mari and I but Chris understood that in a partnership, giving credit where credit is due means a lot.

Chris loved France and I have come to love the country as well. Since 2016, I have published three books there. And one of the joys of going on book tours or attending book festivals in France was getting to spend time with Chris. Like any good Japanese traveler, I’d always bring a souvenir and since Chris had an appreciation for booze, usually Japanese whisky. Before Suntory Hibiki prices went sky-high and when they still sold mini-bottles of the 17-year old Hibiki on the cheap (I killed that market—I am sorry), I brought him a full bottle. He loved it unabashedly. In turn, he tried to teach me to appreciate good wine—not successfully. I brought some plum wine for Mrs. Dickey; he told me she liked it. I hope she did.

I have a bottle of incredibly good whisky that I was going to bring to France for Chris this year. I have no idea what to do with it but Chris would certainly argue that whisky was meant to be drunk and not admired, and best shared with someone else. If I can ever leave Japan, I’ll drag it to the Daily Beast offices and have a toast to the best world news editor who ever lived.

Chris was never overly critical but also rarely laying on the praise. So when he wrote back once, “Brilliant piece, Jake. I am still about 30 mins from my computer but am not going to make any significant changes and have no questions”—that was a lot of validation.

Jake Adelstein has been an investigative journalist in Japan since 1993 and works as a writer and consultant in Japan and the United States. He is also an adviser to NPO Polaris Project Japan, which combats human trafficking and the exploitation of women and children in the sex trade. He is the author of Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan and The Last Yakuza: A Life In The Japanese Underworld.

Neri Zilber

I was truly shocked and saddened to hear of Chris' sudden passing. My heart goes out to his wife and family and to the entire Beast family. He was hands down the best editor I've worked with/for, old school in the best sense of the term—elegant, literary, extremely informed yet confident enough to let his writers write. His enthusiasm for the world and why these stories matter shone through in every note and edit. I only met him once in person, on a rainy summer day at a random brasserie on the Upper East Side. Over drinks he told me about his time covering what he liked to refer to as the Holy Land. My last piece for him was a deep dive into the story of an Israeli gangster, Palestinian security forces, and the curious case of a stolen horse. I shot him a long-ish pitch explaining the broad strokes, because who else but Dickey would ‘get it,’ you know? His one-line response: “I love it. Can you file by tomorrow morning?” May his memory be a blessing.

Neri Zilber is a journalist on Middle East politics and an adjunct fellow of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Jesse Rosenfeld

No editor that I have worked with has done more than Chris to make me a better reporter and writer.

Although we never met in person, he was there for me for six years, always ready to hop on Skype or WhatsApp to work through a story or check in on my safety. He taught me how to tell stories differently, how to make strangers feel familiar, make distant events both relatable and gripping to readers and showed me how to use color to display nuance in reporting.

Chris saw me through wars, revolutions and repression across the Middle East, making me a better journalist every step of the way.

He first took me on after I cold-pitched him a story on student protests against the coup when I was living in Cairo in 2014. From then on—whether I was in Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories, Iraq, Turkey, Lebanon or elsewhere, Chris was there for me.

He was patient and dedicated, always open to a new angle or idea as he taught me how to make stories jump off the page at American readers.

“There is a real journalist in there, Jesse, and we are going to pull it out of you,” Chris told me on a call during the 2014 Gaza war as we were going back and forth on an edit. The line cut twice as Israeli airstrikes shook my Gaza city apartment but Chris kept calling back until we finished the discussion, producing what turned out to be one of the most important stories we did during the war.

From looking out for me when I was alone and under bombardment to dark, humor-laden chats despairing about world events and reaching for a silver-lining twist, Chris was a real mentor and friend. Above all, he helped me find my voice as a journalist and I am eternally grateful that he never stopped trying to pull the real reporter out of me.

Chris was a both a legend and a kind editor who lifted up his reporters, I will miss him greatly.

Jesse Rosenfeld is a Canadian journalist based in the Middle East since 2007. His work has been published with the Nation, the Guardian, Al Jazeera English, Le Monde Diplomatique, the Toronto Star and the National among others.

Ingrid Arnesen

Chris cared deeply. He knew the limitations one might face. He would simply say “are you okay?” even if not on a story. Just checking in. One unforgettable quality was his sense of “deadline.” Chris redefined it. There wasn’t one actually, although there could have been reasons to rush. Chris somehow avoided the term while gently saying “how’s it going.” There are countless attributes that few could hold at once like Chris, that gave one the confidence ... and simply, the sheer joy of writing. To Carol and his family, you shared Chris with us through all the hours, day and night, we’d be calling Chris from wherever we were.

Ingrid Arnesen has covered major political and humanitarian crises worldwide for CBS News, ABC News and CNN, including the wars in Kosovo, Iraq and Afghanistan. She received the Columbia-Alfred I. Dupont Gold Award and Edward Murrow Award for her coverage of Haiti in 1994.

Donald Kirk

In decades in this business, I can count on fewer than ten fingers the number of really good editors I’ve had. Chris was undoubtedly the best. Creative, open-minded, always behind you, got the stuff out there when he said he would, knew what he wanted and what he didn't want. Asked the right questions and accepted the answers. A true rarity. Also a talented writer and thinker, as few editors are. It was an honor to share two or three bylines with him since first filing for him before the Pyeongchang Winter Olympics in Feb. 2018. Last time I wrote for him about a week ago, I hardly remember what, just that he asked a few questions, gave a few hints as to what might work, got me doing a piece that was different from the others, as he always insisted. Demanding, gifted, on your side. Can one speak better of an editor?

Donald Kirk is a journalist and the author of several books about Asian affairs, including Korea Betrayed: Kim Dae Jung and Sunshine and Okinawa and Jeju: Bases of Discontent.

Jeremy Kryt

It’s rare in life that we ever come to know our heroes. Indeed, it is often said that we’re better off not knowing them at all. Lest their legends prove lesser to the true. But such was not the case with Chris Dickey.

For years before we met, I’d studied Chris’s celebrated exploits as a war correspondent in places like El Salvador and Nicaragua. His work—especially With the Contras, which is still the best book I know of its kind—served as both inspiration and exhortation to me while covering some of the same ground he had trod in Latin America. So I felt very lucky to meet him, back in 2015, and very honored to join a World Desk that included so many gifted and intrepid reporters. For his part, Chris more than lived up to his legend.

As for his intellectual prowess, his generosity as a mentor, I can only echo the many moving tributes assembled here. Chris did truly have a poet’s ear for language. And a seemingly boundless knowledge base, befitting of the Renaissance man he was. Blessed too with compassion to match his acumen. Always checking in on you in the field. Always worried about your safety. Always asking the right questions to “advance the narrative,” as he would say. His final note came through just hours before he passed, and it was replete with editorial wisdom, as ever.

What began some five years ago as workaday correspondence eventually blossomed into friendship. I felt it a great privilege to hear the stories of his epic travels. Of his childhood with his illustrious father, James, whose poetry and fiction I’d also long admired. And his sage reflections on art and history and politics.

A few weeks ago, during a conversation about the ongoing struggle against repression and tyranny in many parts of the world, Chris wrote something that I’d like to share. A quote that would seem to illuminate a philosophy honed through years of working in the field:

“I think it is impossible for any person of conscience to spend much time in countries with vast disparities between grinding poverty and egregious opulence and not feel an identification with those fighting for justice.”—Chris Dickey

Godspeed, Maestro. Long and long you shall be missed.

Jeremy Kryt is a correspondent for The Daily Beast, and his work is also featured in Sierra Magazine, The Huffington Post, In These Times, and Earth Island Journal, among others. He's a graduate of the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop and Indiana University.

Will Cathcart

As World News Editor for The Daily Beast, Chris passed on his untold knowledge as a reporter and his common sense as a writer. As an editor, he gave us his patience. He gave us his time.

That’s why this copy is without its editor, and this correspondent is without his hero.

He once told me, in convincing me not to go chase after some war zone, that no story is worth dying for. This was, of course, ironic because Chris spent most of his career covering war zones long after he settled down in Paris in 1990.

Chris helped so many of us tell our stories. And then he corrected our grammar. For the rest of my life, I’ll be rereading the writing guide he would send out with slight frustration to all of his writers every several months as a gentle reminder.

Of his writers, Chris demanded both rage and elegance—erudition and urgency. You had to reach for that unnameable thing within you. And finally, when that story was written. When all of his questions had been answered. Chris might even say “well done.”

Then he would ask for one last rewrite, in time to file by morning.

The last time I saw Chris Dickey—the last time I will ever see him—was on a platform across the tracks in the Paris Metro. I was in town and we met for lunch. I told Chris about a novel I was writing and how I was stuck.

His eyes lit up and he said, “There is a place you need to see.”

Chris took me to this obscure museum called the Musée de la Vie Romantique. Indeed that place connected the dots. It helped get me where I needed to go.

Chris spent so much of his free time taking photographs of Paris, wandering its streets, and finding images that no one else could. Many of these photographs can be found @csdickey.

It comforts me that a man who spent so much of his life covering conflict found such catharsis in collecting light from that ancient city.

As we left the museum walking toward the metro station, we passed by the Moulin Rouge. Ignoring the trappings of its many clichés, Chris, pointed to the subway map. He explained that we would be headed in opposite directions.

“I have an idea,” Chris said in his way. “Across the tracks, I’ll take a photo of you, and you take one of me.”

The photos didn't come out so well, especially mine. But it occurs to me now the significance of each of us waiting for a train that would forever take us in two different directions.

Will Cathcart is a journalist and editor based in Tbilisi, Georgia, covering geopolitics and culture for The Daily Beast, CNN, Foreign Policy, and others. He is a former media advisor to the president of Georgia.