Long before he died in 1983, George Balanchine had established himself as the 20th-century’s most important ballet choreographer. How a poor boy who was born in pre-revolutionary Russia and fled the Soviet Union at age 20 managed to accomplish this feat is the subject of Jennifer Homans’s massive new biography, Mr. B: George Balanchine’s 20th Century.

Homans trained in dance at Balanchine’s School of American Ballet and is currently the dance critic for The New Yorker. She is the ideal person to tell Balanchine’s story. She is able to bring Balanchine’s dances to life, even for readers who have never seen them, through her detailed descriptions, and she never lets us forget the dark shadow the repressive Soviet Union cast over Balanchine both when he was growing up and later during the Cold War.

In Balanchine’s hands, modern ballet was no longer primarily about telling a story or completing a narrative. Just as for an abstract artist such as Jackson Pollock, the paint on the canvas is the true focus, for Balanchine the true focus of ballet is the body in motion.

But in Balanchine’s case, there was nothing abstract about his plotless ballets. As he repeatedly acknowledged, they were built around the movement, shape, and drive of the individual dancer.

“A writer sits in a room alone with paper and pencil and what comes out is himself. It represents him, but a choreographer works with living muscles, with dancers who are all individual people,” Balanchine insisted. “If you take away a specific dancer, the step remains, but performed by someone else it may be nothing.”

The miracle is that Balanchine arrived at such a view of the future of ballet and realized it with the New York City Ballet. There he was able to develop a company in which his work could be performed by dancers he had trained.

Balanchine’s was admitted into Russia’s Imperial Theater School at age nine at a time when the school was in need of boys. His years there were marked by the hardships brought about by World War I and the Russian Revolution of 1917. When in 1924 Balanchine and a small group of dancers left the Soviet Union to begin a summer dance tour, it was just months before the Moscow Soviet closed all studios and companies practicing new dance forms.

In Europe Balanchine had success dancing and composing for Sergei Diaghilev’s innovative Ballets Russes, but his own company Les Ballets 1933 folded quickly. What gave Balanchine the artistic independence he wanted and brought him to America in 1934 was the partnership he formed with Lincoln Kirstein, a rich American drawn to the arts. Three years younger than Balanchine, Kirstein was hoping to start a ballet company in America that would rival any in Europe.

At six feet three and 250 pounds, Kirstein did not look like a man who would become a major figure in the ballet world, but he was just the backer Balanchine needed to make his vision for a new kind of a ballet company in America a reality. In a letter he wrote to a friend whom he thought would help him with financing a ballet company for Balanchine, Kirstein spelled out his faith in Balanchine’s genius. “He is an honest man, a serious artist, and I’d stake my ife on his talent,” Kirstein wrote. “He could achieve a miracle—and right under our eyes.”

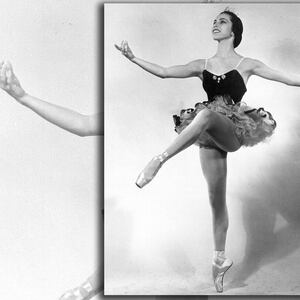

Russian-born American choreographer George Balanchine (1904 - 1983), 24th August 1965.

Rowntree/Express/Getty ImagesMiracle was the right word to use. When Balanchine and Kirstein began the School of American Ballet in 1934, they were not only gambling that Balanchine’s work would attract an American audience. They were gambling that their undertaking could survive the Great Depression.

The gamble paid off, though at first it required Balanchine working overtime as ballet master at the Metropolitan Opera and choreographing both for Broadway, On Your Toes (1936), and Hollywood, The Goldwyn Follies (1938). Even in this period Balanchine was able to pursue his own ballet choreography, beginning work on his masterpiece The Four Temperaments with music he commissioned in 1940 from Paul Hindemith.

But it was not until World War II concluded and Lincoln Kirstein returned to New York after serving in the Army that Balanchine was able to find a secure dance home in New York at the City Center of Music and Drama and in 1948 form the New York City Ballet. Balanchine was finally able to gather around him and train the dancers—among them Jerome Robbins, Jacques d’Amboise, Melissa Hayden, Diana Adams, and Tanaquil Le Clercq—who would form a company that could perform his ballets the way he wanted.

Russian born American choreographer and ballet dancer George Balanchine (1904 - 1983), co-founder and artistic director of the New York City Ballet, working on dance movements with a group of female dancers, 1962.

Ernst Haas/Hulton Archive/GettyFor Balanchine, who had come to New York hoping, as he put it, to create a “cathedral of ballet,” the cathedral was still not complete. New York City Ballet needed an endowment it could rely on and a bigger home in which to perform. The seeds for the endowment were supplied by the Ford Foundation, which in 1963 announced a grant of $7,756,000 to strengthen classical ballet in America and awarded Balanchine’s School of American Ballet $2,400,000 to be spent over 10 years, and New York City Ballet $2,500,000. The new home, New York State Theater, came with the building of Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts and opened in 1964.

After more than 40 years of roaming, Homans writes, Balanchine had his own theater—“our church” as he called it, and he made sure the church lived up to his specifications. He insisted on the stage having a sprung wooden floor that would ease the dancers’ landings and an orchestra pit with enough room to accommodate a symphony orchestra. As for the audience, Balanchine got the nonhierarchical seating he wanted. All the New York State Theater’s 2,729 seats are within 100 feet of the stage and there are no boxes for the wealthy.

What followed was a golden era for New York City Ballet in which Jewels, an evening-length, three-act plotless ballet featuring music from three different composers could be staged and become a huge hit. Balanchine was able to bring in new dancers, expand his old ballets as well as give them larger casts, and for his repertory he brought back old dances from Russia’s imperial past. He was even able to afford a fully equipped costume shop for his dancers. “His rule was personal,” Homans notes, “he knew everyone from the principal dancers to the musicians, dressers, costume designers, stage managers, and lighting techs down to the lowliest stagehands.”

Such control gave New York City Ballet artistic coherence and Balanchine the freedom to do the unexpected. He was able to help Arthur Mitchell, one of his principal dancers, found with Karel Shook the Dance Theater of Harlem. But so much power in the hands of one man also created problems.

“Ballet is woman,” Balanchine said over and over. For Homans that statement is particularly revealing. Balanchine not only needed great dancers, she writes, “he needed to be physically attracted to a dancer.” The problem was that if the dancer wanted a boyfriend or a married life, Balanchine would take offense. When in 1969 Suzanne Farrell, the most important dancer in New York City Ballet in the 1960s, married Paul Mejia, another dancer in the company, Balanchine forced Mejia and Farrell out of New York City Ballet. She did not return to perform in New York City Ballet until 1975.

Homans does not gloss over this side of Balanchine, but she has no doubt that his achievements greatly outweigh his personal flaws. When Farrell returned to New York City Ballet, Balanchine put her back in her old parts and their new relationship stayed strictly formal as the company thrived with her added presence. For Balanchine, making ballets subsumed all else, and Mr. B concludes with Homans observing that Balanchine’s balletic tribute to the human body came in a century that left death and broken bodies everywhere, especially in the country of his birth.

Balanchine’s own death came without fanfare. After a series of illnesses that reduced him to getting around his apartment on a walker, Balanchine died of pneumonia at New York City’s Roosevelt Hospital, just blocks from New York State Theater, which had been his last and best American home.

Nicolaus Mills is professor of literature at Sarah Lawrence College and author of Winning the Peace: The Marshall Plan and America’s Coming of Age as a Superpower.