As if the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) doesn’t have enough problems with facility overcrowding, criminal recidivism rates in the stratosphere, as well as the seemingly endless Jeffrey Epstein saga—along comes two more scandals to further sully the bureau’s already damaged reputation.

Just this past week, three female inmates testified during Senate hearings that through coercion and blackmail, they’d all been sexually assaulted by corrections officers on multiple occasions while incarcerated. The Senate subcommittee assigned the task of investigating the issue found the Bureau gridlocked with thousands of complaints and, as a result, very few of the offenders were being held accountable for their alleged surreptitious and serial predation.

The federal government has always been aware that prison rape and sexual assault have been a reality in the system, which is why the Prison Rape Elimination Act drew bipartisan support when it was proposed and enacted in 2003.

But I don’t think our lawmakers understood the extent to which the Hollywood version of inmate-on-inmate sexual assault was accompanied by its officer-on-inmate counterpart. And it is exactly that component of the prison rape story that has the media and public at large standing at attention.

To make matters worse for the BOP, a recent investigation into the murder of Whitey Bulger—the notorious gangster and FBI snitch—has revealed more incompetence within the bureau’s rank and file. Despite Bulger’s apparent request to be housed in general population, prison officials still should have understood his life would be in danger and not granted his wish. What were they thinking?

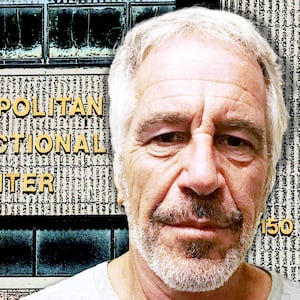

And with respect to my former cellmate, Jeffrey Epstein, a little common sense would have gone a long way as well. The guy had been down to the suicide unit twice in a month. Why would anybody in authority allow him to occupy a cell all alone — which is what MCC’s warden did when Epstein’s cellmate was sent back to general population. Talk about asleep at the wheel!

Part of the problem, in Bulger’s case, stemmed from officers discussing his impending arrival within earshot of inmates, thereby notifying dangerous criminals and enemies of Bulger’s crew that an opportunity to right a few wrongs was imminent.

In today’s prison ethos of “give respect/get respect,” guards have become surprisingly chummy with inmates and often share gossip with the boys. That sad fact apparently prepared Bulger’s murderers. And allowing Bulger to be housed in g-pop sealed the deal.

While I was incarcerated at the federal Metropolitan Correctional Center in Manhattan, I appreciated that most of the guards acted like human beings — and I even counted a few of them as friends. But “give respect/get respect” doesn’t include gossiping like ladies at the beauty parlor. Just because inmates do it (trust me, they do) doesn’t mean guards should as well. A little more discretion and wisdom might have saved Bulger’s life — and the BOP a truckload of embarrassment.

Stating there’s a problem with officer-on-inmate sexual assault is easy. Offering a way to rectify the situation is another matter entirely. The Senate investigation seemed to conclude (if you read between the lines) that the concept of the old “blue wall of silence” has been in full effect. Even when officials knew of sexual predation, they seemingly protected their own from punishment. Obviously, that has to stop. Severe penalties for those who would protect the guilty need to be put in place, and all parties should be viewed as “acting in concert.” That should effectively shatter the blue wall.

I would say that requiring orientation and coursework to prevent sexual predation would be paramount. But in at least two cases, the worst of the offending officers were actually the teachers of those already-existing classes.

My education during the year I spent at MCC federal prison enlightened me to the fact that many of the officers watching over me were, by their own admission, suffering from PTSD after having served in the military in Iraq and Afghanistan. Not all of the officers were mentally operating at 100 percent.

The BOP has its requirements for prison guard employment. But I’m not sure the psychiatric evaluation of its applicants is sufficient. The Bureau needs to delve into the psyches of their employees more thoroughly to weed out the bad apples.

Limiting the number of months or years an officer can remain watching prisoners at any given facility could curb some of the ongoing activity. Not every officer would be willing to “go on the road.” But a pay incentive might attract some while mitigating the problem of guards growing comfortable at facilities where they can do as they please with little threat of oversight.

Whether anybody in a position of authority would take my suggestions seriously or not, I think they’d have to admit that the current situation is in dire need of remediation. Prisoner complaints can’t be ignored or shelved. And there’s no excuse for the current backlog of cases that are protecting the guilty.

Prison is a bad enough deal to begin with. To suffer sexual assault and/or rape isn’t part of the prescribed punishment. And those in charge need to deal swiftly and emphatically with the guilty. Guards can no longer rape and pillage without answering for their crimes. Somebody has to take the bulls by their horns.