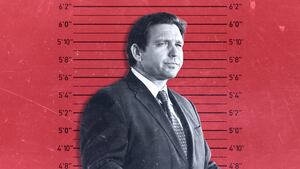

Last week’s flight of about 50 migrants from San Antonio to Martha’s Vineyard, orchestrated by Florida’s Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis, was an unscrupulous stunt.

It’s unlikely that it ruined any lives, for the migrants are already bringing a lawsuit against DeSantis, and media attention for their plight will probably bring them further support most new arrivals don’t receive. Still, the scheme was by all accounts deceptive, spiteful, and trollish.

At least, that’s what it looks like to those, like me, who favor a much looser immigration policy than we have right now.

A widely shared Washington Examiner editorial, by contrast, made the case that the flight was downright necessary, a desperate plea for national attention to a national crisis suffered disproportionately by a few border states. I don’t find the Examiner’s case convincing, especially in its assertion that the media is simply ignoring a major story “in order to protect” President Joe Biden. But if the article’s claim of urgency strikes you as incredible—as in, literally unbelievable as a sincere argument a real person could make—perhaps it’s because you have a higher tolerance for disorder.

We usually think about tolerance for disorder in much more domestic terms, as in: “Do you like to keep a neat house?”

That makes sense, because it’s a pre-political impulse, partly determined by personality but also greatly affected by culture. And on the cultural scale, particularly when we look beyond the home to matters of public order, Americans’ tolerance for disorder varies widely and often maps along familiar political lines. Conservatives and others on the right tend to have lower tolerance for disorder; progressives and the left generally have a higher tolerance.

This isn’t a comprehensive theory of American society. Order is sometimes in the eye of the beholder, and “order” in political parlance has seen plenty of misuse. Yet, with all due qualifications, I think we recognize this spectrum at a basic level.

It’s the distinction in the landscaping in that great New Yorker cover from last summer, in which the “Republican’s” rowhouse has tidy box hedges, stringent mulch lines, and a short-shorn lawn, while the “Democrat’s” pollinator garden—duly labeled with a bee-festooned yard sign—is a tangle of thistles and dandelions. That’s not only an expression of different environmental views or aesthetics. It’s also about order, propriety, and assumptions about what a public space should be like and what will encourage others toward orderly behavior.

Tolerance for disorder isn’t relevant to every political question, but it certainly matters for immigration over the last half-decade. Migrant arrivals along the southern border are at a record high. Cities like Yuma, Arizona, and El Paso, San Antonio, and Brownsville, Texas receive hundreds or even thousands of migrants on a weekly basis. Thousands more have set up encampments on both sides of the border—or directly on bridges across the Rio Grande—and images from those makeshift spaces show crowds and chaos.

There’s a reason former President Donald Trump and his disciples, like DeSantis, think it’s effective politics to play up that chaos, to sensationalize and hyperventilate about an “invasion.” The reason is that, for many Americans, those images already produce an instinctive unease, an anxious feeling that this is indeed a crisis, that order must be restored. That impulse doesn’t only lead to calls for stricter laws or harsher enforcement; it’s also part of why border states have an array of charities and social services dedicated to helping migrants find their footing in the United States.

But it does say, loud and clear, something must be done about this, now.

That instinct isn’t universal, at least not to the same degree. (The most vivid contrast might be San Francisco, with its long standing reputation for acceptance of public disorder, from the benignly weird to the deeply troubling.) And failing to realize our variance here will only make immigration reform more difficult, because discomfort with disorder is difficult to suppress and can’t be legislated away.

This is where pro-immigration arguments which focus on justice, cultural diversity, freedom of movement, the American dream, streamlining bureaucracy, or economic benefits can’t do much good. They’re important, and they’re the kind of argument I’m inclined to make when talking about immigration. But they can’t allay the automatic discomfort many people feel when presented with disorder at the border—and the more disorderly the border is perceived to be, the more Americans will make restoring order their priority in immigration reform.

And if that priority isn’t addressed, if Congress spends another 36 years failing to pass a major immigration bill, we’ll continue to have both a crisis at the border and a deeply felt need in American politics left open for exploitation by politicians with sensational rhetoric and unscrupulous stunts.