“Justice for Denise! Justice for Denise!”

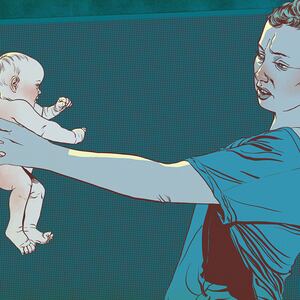

A group of approximately 30 protesters huddled together in front of the Pavilion at Queens Hospital Center and chanted the three-word refrain in unison. It had been over 50 days since Denise Williams’ untimely and unexpected death at Queens Hospital. Just a few weeks after the 29-year-old gave birth to her second child, she had sought emergency psychiatric care there for severe perinatal mood and anxiety disorder (PMAD), colloquially referred to as postpartum depression.

On Aug. 30, two days after Williams was admitted to the New York City Health + Hospitals facility, Williams’ mother Linda Magee received a call from an unknown 212 number. The coroner on the other end of the line informed Magee that her daughter had died and that she needed to come identify the body. New York City’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Queens Hospital, and the New York City Health + Hospitals Corporation refused to provide Magee with information about what happened to her daughter.

ADVERTISEMENT

This latest rally, held on the bright, crisp morning of Oct. 17, was the third of its kind and by far the largest. The attendees’ demands to the city were clear—give the family an explanation for the cause and manner of Denise Williams’ death and fix the maternal health-care system that allowed it to happen. “No woman, nobody, should go into a hospital to get treated for depression and come out dead,” Williams’ sister, Belinda, exclaimed, holding back tears.

Four days later, on Oct. 21, New York City’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner provided The Daily Beast with a cause and manner of death: While admitted in the psychiatric department at the New York City Health + Hospitals facility for the Williams died naturally from a pulmonary embolism that had gone undetected. She left behind an 8-week-old and a 3-year-old.

For Williams’ family, nothing about Denise’s death, or the city’s handling of it, has seemed natural. Denise Williams experienced some of the most severe mental and physical health complications that a new parent can experience in the first weeks of her fourth trimester, the 12-week period immediately after giving birth when more than half of all pregnancy-associated deaths occur. By the time Williams was able to access emergency psychiatric care at Queens Hospital, after weeks of suffering without treatment, hospital staff didn’t catch the physical condition that ultimately killed her.

Her death highlights what Williams’ family and many birth justice advocates consider to be huge gaps in maternal health-care policy, particularly on postpartum care. In New York City alone, at least four Black women, including Williams, have died giving birth or within the first 42 days postpartum since the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in early March 2020.

That’s emblematic of a larger trend in the U.S. maternal mortality crisis, where Black women die from pregnancy-associated causes at 2.5 times the rate of their white counterparts.

Attention to Williams’ death, and the larger issues surrounding maternal mortality and postpartum care in the U.S., comes at the same time Congress negotiates key social policies in the Build Back Better Act. On Thursday afternoon, Vice President Kamala Harris confirmed in a tweet that Build Back Better would contain many of the provisions of the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act, a win for advocates and policymakers alike.

One such provision makes federal funding permanently available for every state to expand Medicaid coverage up to one year postpartum. Currently, only three states in the country provide continuous postpartum Medicaid coverage for the full 12 months. A bill in Albany that would extend New York Medicaid coverage from 60 days to one year postpartum passed the state Senate in June and will be taken up again in the coming legislative session.

According to a report from the Century Foundation, maintaining continuity of care through the postpartum period is “vital for screening and treatment for physical, mental, and behavioral health issues” that arise in the fourth trimester. For birthing people on Medicaid, who accounted for approximately 43.1 percent of births in 2018, maintaining their insurance coverage for the first year after childbirth could save their lives.

Even with expanded Medicaid coverage, however, many experts argue that U.S. postpartum care is insufficient. Many states’ Medicaid plans, and most private health insurance plans, don’t cover postpartum doula care or mental and behavioral health care for PMADs, for example. Paige Bellenbaum, a PMADs expert and founding director of the Motherhood Center, cites insurance as one of the major barriers to accessing adequate postpartum care, especially for PMAD treatment. “What insurance companies are willing to cover in the field of behavioral health,” she says, isn’t nearly enough for practitioners like her to keep their businesses open. As a result, many postpartum behavioral health practitioners and postpartum doulas are out-of-network and unaffordable for most low-income new parents.

Germany, on the other hand, provides new birthing parents with at-home midwifery visits every day until 10 days post-birth, and an additional 16 visits as needed through the first eight weeks postpartum—all fully covered by the country’s nationalized health-care system. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) estimates that up to 40 percent of birthing parents in the U.S. never attend the one recommended postpartum checkup most insurance companies cover. And while all Medicaid plans under the ACA are required to cover midwifery care, including midwifery postpartum visits, there are far too few midwives across the country to meet demand.

The at-home visits that midwives, doulas, nurses, and community health-care workers provide are vital for diagnosing serious physical and mental health complications that occur in the postpartum period before they become life threatening—as was the case for Denise Williams. Pulmonary embolisms in the postpartum period are difficult to detect. When caught early, however, the Cleveland Clinic asserts that they’re easily treated. With regard to PMADs, “80 percent of all cases… go undiagnosed and untreated, because of the stigma and the shame that surrounds maternal mental illness” said Bellenbaum. New York City was slated to launch its first postpartum home-visiting program in early 2020, but city officials scrapped its New Family Home Visits program due to COVID-19.

One of the biggest barriers to accessing postpartum care is a lack of paid parental leave. After days of public backlash to President Biden’s announcement last Thursday that the final Build Back Better bill would contain no paid family or medical leave, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced on Thursday that her Democratic colleagues intend to add four weeks of paid leave back into the bill. While a welcome step, experts agree that a new birthing parent needs a minimum of six to eight weeks just to recover physically from childbirth.

In the meantime, Williams’ family continues to demand justice for Denise. Health + Hospitals said in a statement that both the agency and Queens Hospital representatives have been in frequent communication with Williams’ family, a claim the family disputes. On the delay in autopsy reporting, the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner pointed to a recent Mayor’s Management Report, which shows that Williams’ autopsy was produced well under the average 144 days the office has taken to complete autopsies in 2021. Abe George, the lawyer representing the family, said he and the family will decide whether to move forward with a lawsuit pending an expert’s review of Williams’ medical records.

On Nov. 14, Williams’ family and a coalition of birth justice activists will hold their fourth rally for Denise outside Queens Hospital Center. Shawnee Benton Gibson, whose daughter Shamony Gibson died from a preventable pulmonary embolism in 2019, made the call to action clear at the Oct. 17 rally: “If there’s anyone out here who has a new mother in their lives or family, check in on them. Because we stigmatize… Black and brown women who are not mentally stable… So ask if they are OK. Ask their mate if they are OK. Cause if they’re both not OK, the babies are not going to be OK. Black wombs matter. Black minds matter. Black bodies matter. Black communities matter. Justice for Denise.”